3.2 Health and wealth

While all classes regarded good health as desirable, access to various means of preserving or promoting it varied according to economic circumstances. For the upper and middle classes, with substantial amounts of disposable income, a wide range of options were available. They could access information about how to protect their health through books and articles in magazines. Many of these books were written (or at least claimed to be written) by doctors and other health-care professionals. An article about pregnancy in the opening number of Woman magazine in 1932, for example, was allegedly written by ‘Mumsie, the wife of a famous children's doctor’ – a persona neatly combining medical authority and the status of an ordinary wife and mother (Beddoe, 1989, pp. 14–15). The 1920s saw a boom in baby-care books, aimed at middle-class mothers, which not only gave practical advice on feeding, bathing and clothing, but also set out the stages of physical and psychological development, thus unwittingly creating the first generation of mothers worried that their babies walked and talked ‘late’ (Unwin and Sharland, 1992).

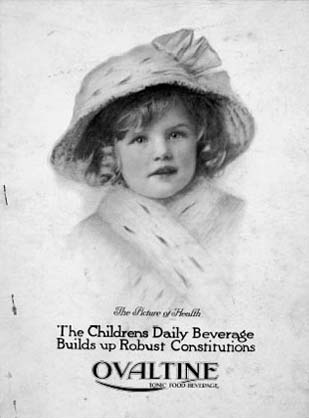

Generally, the wealthier classes enjoyed the sort of varied diet thought to promote good health. They could afford meat, fish, fresh fruit and vegetables (Burnett, 1979, pp. 213–39). However, some wealthy individuals worried that they ate too much, and dieting to obtain a slim figure was a well-established activity by the 1920s. Others were concerned that their diet was too rich, and in the pursuit of health adopted simple, more ‘natural’ diets. They stopped consuming alcohol, tea, coffee and meat, and ate fruit, vegetables and cereals (the word ‘muesli’ was adopted into the English language at this time). The popularity of ‘health foods’ (such as ‘Hovis’ wholemeal bread) and vegetarianism grew from the mid-nineteenth century to become a mass movement in Germany and surrounding states by 1900, although it was much less popular in Britain. The quest for a healthy diet was closely linked with other movements – such as unorthodox medicine and feminism, whose supporters argued that overly elaborate diets tied women to the kitchen (Meyer-Renschhausen and Wirz, 1999). Even ordinary foodstuffs were marketed for their health-giving properties (Figure 2).

Exercise and fresh air, two more building blocks for good health, would appear to be open to all. However, only the upper and middle classes had the cash and the leisure time to participate in the craze for healthy exercise which began in the late nineteenth century. They could afford to buy bicycles, tennis rackets and golf clubs. They could also, following the German example, go rambling and hiking in the countryside, and pay to attend gymnastic exercise classes. Exercise was clearly gendered. Men and boys took part in team games (such as rugby, football and cricket), athletics and German gymnastics, which made use of apparatus such as vaulting-horses and parallel bars. Such activities were thought to develop a competitive spirit and build strong muscles, desirable qualities in the next generation of workers and soldiers. Women, too, were encouraged to exercise – not to build muscles, which were regarded as undesirable in the female sex, but to cultivate health. For women, exercise was thought to prevent curvature of the spine, chlorosis (a mysterious complaint, whose main symptoms were tiredness and a pale complexion) and hysteria, and a strong, fit body was thought to guarantee easy births and healthy offspring. Cycling, tennis, golf, team games requiring skill rather than strength (such as hockey) and Swedish gymnastics, which involved stretching the body with the aim of developing flexibility and coordination, were seen as beneficial forms of female exercise (Fletcher, 1984, pp. 1–55; Stewart, 2001, pp. 151–72).