2 Patterns of disease

Before looking at how people dealt with ill health, you need to know what sort of medical conditions were prevalent. Between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, all over Europe, the prevailing pattern of mortality changed. Infectious diseases, which had killed huge numbers of people, were gradually brought under control. As life expectancy increased, degenerative diseases, associated with old age, began to cause more deaths. However, although people were living longer, they actually spent more time off work because of illness. James Riley's studies of the records of friendly societies, which offered health insurance (these are discussed in more detail later), have shown that workers were no longer dying from infectious diseases. Instead, they survived illness, but spent a long time recovering their health and strength (Riley, 1989, pp. 159–92).

The friendly society records show that the complaints that caused workers to take time off were not the same as those that dominate mortality statistics (Table 1).

| Leading causes of death in England and Wales among men, in 1908 | Leading causes of sickness in three friendly societies, 1896–1919 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cause | % of total | Cause | % of total |

| Heart disease | 14 | Accidents | 16 |

| Tuberculosis | 14 | Poorly identified | 13 |

| Old age | 8 | Influenza and catarrh | 13 |

| Cancer | 8 | Bronchitis | 9 |

| Bronchitis | 7 | Rheumatism | 4 |

| Pneumonia | 7 | Lumbago1 | 4 |

| Cerebral haemorrhage | 5 | Gastritis2 | 2 |

| Accidents | 5 | Carbuncle3 | 2 |

| Bright's disease4 | 3 | Tonsillitis | 1 |

| Influenza | 3 | Skin ulcers | 1 |

| Apoplexy | 2 | ||

1Lower back pain, caused by muscular inflammation or arthritis

2Inflammation of the stomach lining, causing pain and discomfort after eating

3A local infection, similar to, but larger than, a boil

4Now recognised as a number of kidney diseases, all associated with the presence of albumin in the urine

(Adapted from Riley, 1997, pp. 191–2, Tables 7.1 and 7.2)

If we ignore accidents and ‘poorly identified’ complaints, the most common ailments among the working-class men insured by the friendly societies were respiratory infections – influenza, colds and bronchitis – followed by joint and muscle problems, such as rheumatism and lumbago. Few workmen reported sick with degenerative diseases. Nor did they take time off for tuberculosis (TB), one of the major killers at this time. TB was a chronic, but not disabling, disease, and men were able to work until they developed advanced symptoms.

Friendly societies insured a select group – fairly young, fit, working men – so their records are not representative of the whole population. General practitioners saw a larger cross-section of society. Records from their practice suggest that they treated a fairly similar range of complaints to those recorded by the friendly societies – respiratory infections, rheumatism and digestive complaints, such as dyspepsia and diarrhoea. GPs did not spend much time treating degenerative diseases since they could do little for such conditions. Their case records show how patterns of disease varied by class, area and season. Middle- and upper-class patients consulted doctors about obesity, gout and nervous complaints – conditions that were rarely reported by working-class patients. The poor suffered from rickets (a consequence of a poor diet), dysentery and diarrhoea (reflecting the difficulty of keeping food clean and fresh) and infectious diseases. GPs working in industrial areas had to deal with the results of accidents and occupational diseases: miners, for example, who worked in a damp and dusty environment, suffered from high levels of bronchitis, pneumonia and pleurisy. Everywhere, the incidence of respiratory diseases increased in the winter months, while digestive complaints were more frequent in the summer (Digby, 1999, pp. 192–3, 208–14).

Men were more likely than women or children to visit a GP (for reasons I discuss later), but not because women and children were any healthier. Children continued to suffer from a range of infectious diseases – tonsillitis, scarlet fever, chickenpox, whooping cough, measles and mumps. A survey of the health of working-class women in the 1930s found that they suffered from headaches, constipation, anaemia, rheumatism, gynaecological problems (often associated with childbirth), bad teeth, and ‘bad legs’, resulting from varicose veins, ulcers and phlebitis (inflammation of the veins) (Spring Rice, [1939] 1981, p. 37).

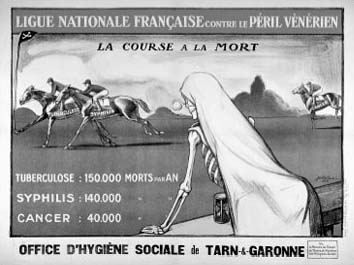

While people suffered from a wide range of complaints, two diseases prompted particular public concern – tuberculosis and venereal disease (VD). Both were seen as causes of national degeneration, causing high levels of disease which weakened the population and led in turn to the birth of feeble children (Figure 1).

There was also a widespread belief among the public and medical practitioners that the pace of modern life – in which information flashed through the air by telegraph, and people travelled by train and steamship at previously unimaginable speeds – caused ill health. The modern lifestyle was associated with physical disorders, including dyspepsia, diabetes and liver complaints. It was also blamed by some practitioners for an apparent epidemic of nervous diseases, such as hysteria and neurasthenia. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, insomnia, pain, involuntary movements and nervous tics were believed to result from the strain of modern life on the nervous system. In Russia, neurasthenia was associated with a cultivated ‘western’ lifestyle (Goering, 2003).