Find out more about The Open University’s History qualifications.

At this time of year, people across the globe will attend Burns suppers. They’ll dine heartily on a meal the centrepiece of which will be haggis, enjoy refreshments which will often include a glass or more of whisky, and listen to several of Robert Burns’s songs, speeches and, if they’re lucky, a spirited performance of ‘Tam o’ Shanter’. The event will culminate in a toast to the Immortal Memory of Robert Burns. Burns, Scotland’s national poet, is a global superstar, celebrated around the world on Burns Night. But why? What are the reasons for this ubiquitous ritual and what is its relevance today?

In 1817, in the cramped graveyard of St Michael’s church in Dumfries, the bones of Burns were exhumed from the coffin in which he had been laid to rest in 1796. The workmen present stood bare-headed ‘their frames thrilling with some indefinable emotion, as they gazed on the ashes of him whose fame is as wide as the world itself’ (Whatley, 2016). The exhumation was in preparation for the re-interment beneath a mausoleum being built as a more fitting memorial to the dead poet. Hardly more than twenty years since his untimely death and already Burns was being revered by his countrymen.

The Dumfries mausoleum was the first of numerous Burns memorials that by the end of the nineteenth century studded the towns of Lowland Scotland. Many were life-sized and above statues, erected in what by the 1870s had become an informal race between Scotland’s urban elites to have one. Overseas, particularly in Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand, Scottish settlers and their descendants followed suit.

Burnomania

The explanation for what one of Burns’ disapproving critics – and there were several, mainly representatives of the Kirk – termed Burnomania, is far from straightforward. The sentimental appeal of Burns’s writing is part of it, in particular his preservation in verse and song of rural and small-town Scotland that was fast disappearing in the march to modernisation. His use of humour, based on his close observation of the foibles of the people around him, combined with his vivid imagination and the remarkable potency of his language that generated popular poems such as the aforementioned ‘Tam o’ Shanter’ are other factors.

But alone they will not do. They only partly explain the intensity of the adoration for Burns and why, from the time of his death, his legacy was contested and considered to be worth fighting over.

Man of the people

Hugely important was Burns’s championing both directly and more subtlety the rights of the common people. In his work he dignified their everyday lives and raised the self-esteem of ordinary Scots at a time in Scotland’s history when this was at a low ebb.

Burns was also not afraid to challenge rank, title and wealth, sometimes to the displeasure of his editors. For example, terrified by the prospect of revolution that might be inspired by songs such as ‘A Man’s a Man’, a hymn to democracy and for this reason feared by the nation’s largely unelected elites, Burns’s first editors removed poems and sections of them that were toxic in their assertion of human dignity regardless of rank, title or wealth.

The poem ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’ was promoted as a model of stoicism and Presbyterian piety for the country’s rural poor to abide by. Yet even in this work there were some subversive stanzas. For example, in one he declared that ‘an honest man’s the noblest work of God’, in contrast to princes and lords who were merely ‘the breath of kings’, pompous and ‘the wretch of human kind’. Such sentiments helped reinforce the demands for democratic rights that were present in the nineteenth century.

Burns was also adopted by the newly ascendant manufacturing and commercial classes. Disciples of Samuel Smiles, they urged working people to emulate Burns on the grounds of his belief in independence – a value that remained deeply embedded in working class culture well into the twentieth century. By the middle classes as well as the Tory-leaning aristocracy, he was portrayed as a credible example of how with hard work and the grace of God (the ‘heaven taught ploughman’) success and fame could on occasion be achieved.

At the same time, moderate Presbyterians as well as non-believers drew on Burns’ anti-clerical satires such as ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’, which contributed to the liberation of the Scottish people from the grip of the nation’s theocrats – ‘Auld Licht’ ministers and kirk session elders, the inheritors of Knox’s Reformation. For many he was no less than a secular saint. By the late Victorian era, Burns had become something of a socialist icon too, leading the way for the Communists to commandeer him in the twentieth century.

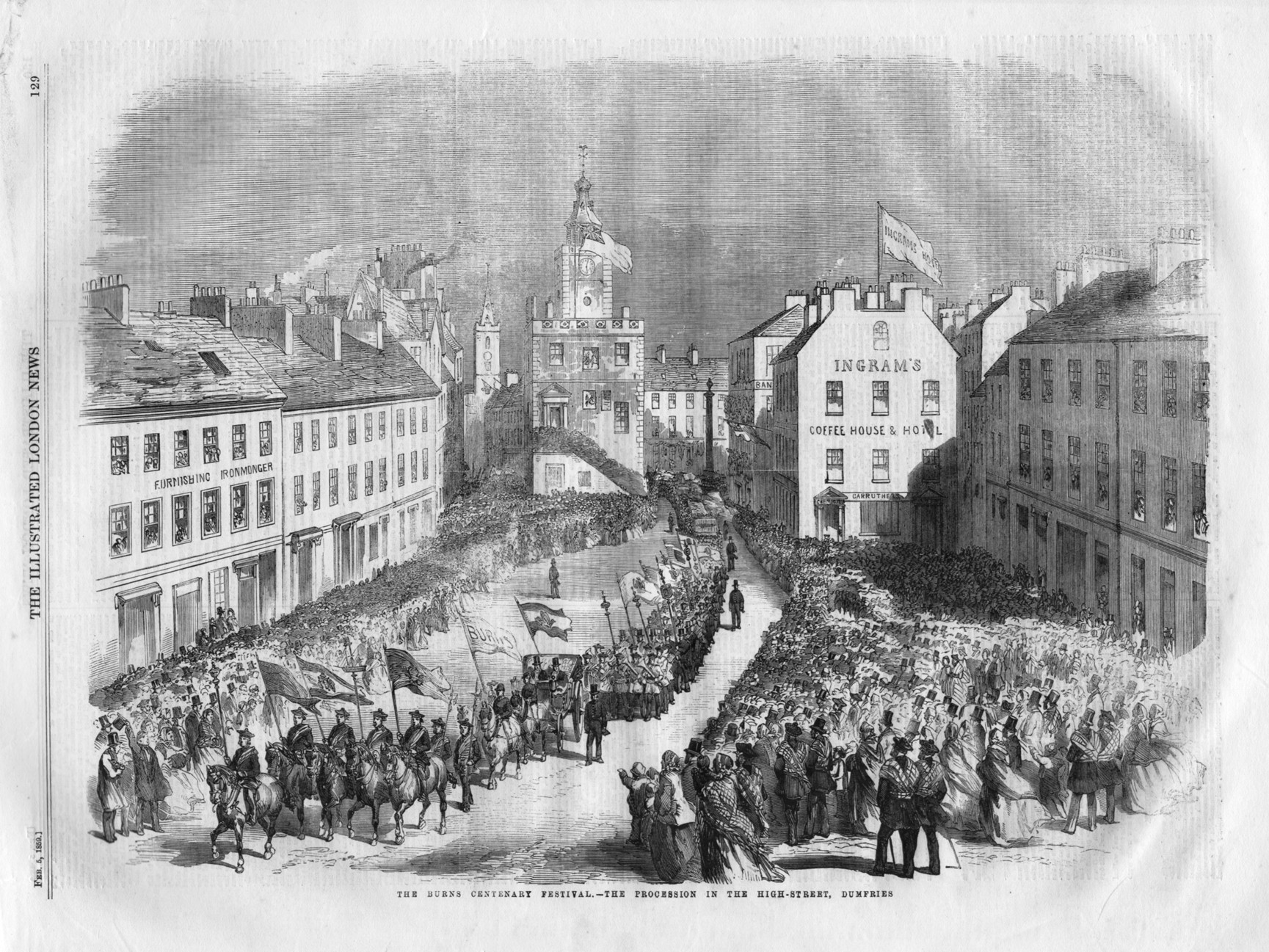

Procession in Dumfries, 25 January 1859; note how thickly packed the watching crowd was.

Scotsman

If motivations for the near universal participation of Scots in this outpouring of affection for Burns differed from place to place, and sometimes according to class, there was one uniting force. As The Scotsman reminded its readers, the ‘chief characteristic of Burns was his Nationality…he was utterly and intensely, before and beyond everything, a Scotchman.’ Indeed, there were those who believed that Burns had rescued Scotland – Scotia - from oblivion, this through his use of Scots words, phrases and rhythms, and work as a collector, adaptor and writer of Scottish song. If Scots felt alienated within the Union in which England was politically and culturally dominant, Burns offered Scots a sense of pride and self-respect that in turn fueled the emerging Home Rule movement.

Today and over this week nationalists will claim Burns as their own. But by judicious selection from his works (and no little credibility stretching), others will demonstrate that Burns was one of them too. It was ever thus.

Burns’s legacy as a moving force in Scotland’s history has now more or less dissolved. Even more so than in the past, he has become a malleable symbol of Scotland, one feature of which is his function as an economically valuable visitor attraction whose familiar face can sell shortbread, whisky, ales and tea towels.

Nevertheless, Burns remains relevant at another level. At the best of the Burns suppers, attendees will have been reminded that Burns spoke for no one party, but for humanity itself, warts and all. More than this, he acknowledged the connectedness of all living things, and the right to life and shelter of even the tiniest mouse.

Currently, with the emergence of an uglier, hard-edged nationalism around the world, political and social polarisation, the uncompromising politics of identity, endemic military conflict and conquest, and the threat of climate-change-induced catastrophe, Burns offers a welcome antidote. His is an eighteenth-century voice that speaks as strongly to us now as it did when he was alive.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews