1 Voice-leading analysis of form

1.1 Identifying the background level of the harmony

If you have studied OpenLearn course AA314_2 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] Harmonic analysis: the middleground you will already have been introduced to the general topic of the background, after the foreground and the middleground levels that you studied in your analysis of Mozart (OpenLearn course AA314_1). This is what one might equally call analysis of ‘form’. The present course, though, will focus on the way that musical form is created from the harmony of the music.

For the time being, I don't want you to think about how to divide up each movement into sections such as ‘exposition’, ‘development’, and so forth. These sorts of labels are important in studying a piece of music, and I will discuss how they relate to harmonic structure at the end of this free course. But first, I want to look at harmony on its own.

In the earlier courses, you saw that the rules that govern how one chord leads to another at the foreground of the music can also be seen to work over longer spans. These voice-leading rules prolong main harmonies as middleground structures. In this course I am going to consider how certain harmonies – that is, certain chords and melodic lines – similarly become the main harmonies for much longer spans of time, ultimately covering the whole of a movement.

I'll begin with the passage of music that was analysed more often than any other in OpenLearn course AA314_1.

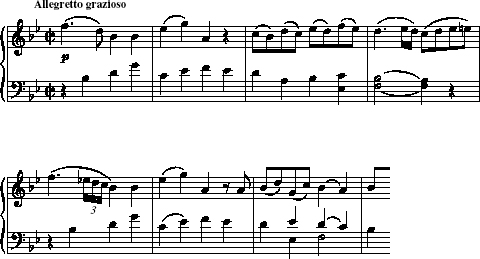

OpenLearn course AA314_1 began by comparing the first eight bars of the last movement of Mozart's Sonata K333 (Example 1) with a pastiche of this style which was musically similar, but artistically awful. Already, it was clear that Mozart's beautifully balanced theme is made up of repeating patterns of notes in an overall downwards shape. This melodic feature – conjunct linear motion in the voice leading – became more prominent in the analysis of these bars in OpenLearn course AA314_2. Examples 2 and 3 reproduce two of the analytical graphs of the first four bars of this theme from OpenLearn courses AA314_1 and AA314_2 respectively.

Activity 1

Look again at the analyses of bars 1–4 of Mozart's theme (Examples 2 and 3). How do these two analyses show features of the foreground and middleground of the music respectively?

Answer

Discussion

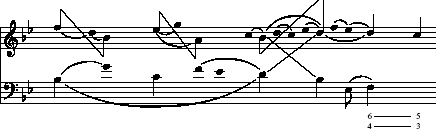

Example 2 shows musical processes at the foreground of the music, because it shows the sequence of consonant harmonies in the score. It omits dissonant notes such as neighbour notes, but preserves the outline of all the ‘vertical’ harmonies between the top line and the bass. This is shown as a simple rhythmic reduction.

Example 3 shows some middleground features of these bars, because it shows that some consonant harmonies are subordinate to others. For instance, the second consonant chord of Example 2, the G minor harmony in bar 1, with B♭as the upper note and G in the bass, is shown to be subordinate to the preceding B♭major harmony. In other words, the B♭ chord is prolonged throughout bar 1, subordinating the G minor harmony. The analytical notation represents this hierarchical observation by giving a stem to the B♭ in the bass, but keeping the G as an unstemmed notehead, and indicating that these notes are related to each other with a slur. This process of prolonging one harmony per bar continues throughout the extract.

Other middleground features of the harmony shown in Example 3 are unfoldings in the top line of bars 1 and 2, and a voice exchange in bar 3. These indicate that the melody derives from a two-part structure at this level.

If you are unsure of the meaning of any of the symbols used in Example 3, or of any of the terms used in the discussion above, check them again in the text of OpenLearn courses AA314_1 and AA314_2, or in the Glossary at the end of this free course.

Now look at the final analysis of this section extending the analysis to bar 8.

Activity 2

Look again at the final analysis of Mozart's theme (Example 4 below). Write down answers to the following questions.

-

What additional feature of the music is analysed in this graph, compared to the previous one (Example 3)?

-

What notes in the top and bottom lines would you keep in a graph of the next, deeper, level of the harmony?

Answer

Discussion

-

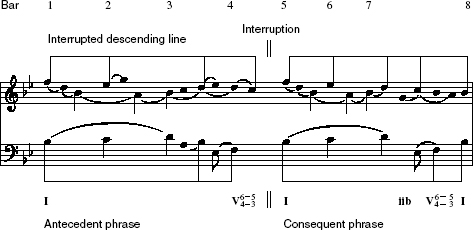

The additional feature of the harmony shown in this graph is the striking linear descent in the melody from the opening F down to the final B♭. This feature controls the harmonic movement of the whole eight-bar phrase, making it a complete course, and a miniature example of interrupted form.

-

In addition to the notes of this linear descent, I hope that you decided that the most important feature of the harmony in the whole section is that it ends where it began, resting on the tonic chord. In other words, the most important notes in the harmony are the initial tonic chord established at bar 11, and the final tonic chord, reached at bar 81 and approached via the dominant chord of bar 72−4 (which is decorated by a subordinate chord and a 6/4–5/3 suspension).

This example looks forward a little to the sort of analysis that you are going to perform with Beethoven's Eighth Symphony. The complete eight-bar phrase derives its beauty and elegance from the simple and logical structure that underlies the exquisite foreground harmony. This structure makes up the form of the section, and can be called the ‘background’ of the harmony.

In order to analyse the form of sections of movements much longer than these eight bars (or the form of whole movements), a few new analytical notation symbols are needed, to distinguish the deepest level of the harmony from the other levels. These symbols can be used to convert the graph of Example 4 to that in Example 5.

Activity 3

Compare Example 5 with Example 4. What alterations have been made regarding the notes included in the graph? What new analytical symbols have been introduced?

Answer

Discussion

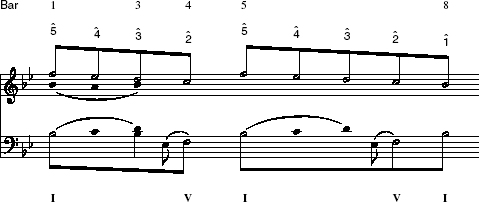

In Example 5, the unfoldings and voice exchange are aligned vertically, to show how the melody is based on two independent harmonic voices. This means that the unstemmed notes which unfold each interval have now been omitted.

The new elements of analytical notation are as follows.

-

The linear descent from F down to the final B♭, and the bass movement from tonic to dominant and back to tonic, are each shown using unfilled stemmed noteheads (which look like minims).

-

This overall structure is shown by adding beams to connect these stems (the beams in Example 4 connect filled stemmed noteheads in this way).

-

The notes of the interrupted descending line have been numbered, according to their degree of the scale. These numbers are identified with carets (which look like circumflex accents:

).

).

Example 5 shows just the same analysis of structure as Example 4; but the new notation will be very useful later, when we look at graphs of much longer spans of music: ultimately, whole movements are based on the same harmonic structures as short musical phrases.

This section has revised the concepts of foreground and middleground, and the notation that goes with them, in order to emphasise again how tonal harmony works hierarchically, and can be reduced to simpler and simpler underlying shapes. Whenever you are writing or reading an analytical graph, keep firmly in mind the fact that the symbols we use do not have the same meaning as they do in a score. A hierarchy based on rhythmic notation in a score is used to show harmonic importance in an analytical graph. So unfilled noteheads (which look like minims) identify the harmonically most important notes, filled noteheads (which look like crotchets) the next most important, and unstemmed noteheads show the notes which are inessential to the level of harmony that the graph is analysing.