4 Voice-leading analysis and sonata form

Sonata form can be divided into sections in several different ways. One of these is to describe it as an expanded version of the binary form of the baroque (Figure 1), emphasising the contrast of key areas within the first half.

Another scheme is to label the sections as a three-part or, sometimes, a four-part sectional form, emphasising the contrast of thematic material. This sort of description was more common in nineteenth-century textbooks, and indeed is better suited to sonata-form movements from the nineteenth century.

Either way of describing sonata form can be applied to the first movement of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony.

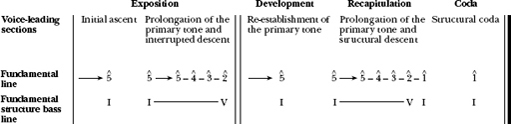

How, then, does this picture of sonata form relate to the fundamental structure of a voice-leading analysis? Are there features of a graph such as the ones we have been looking at which will always map on to sonata form in the same way? It is tempting to assume that there should be. Let's start by looking at how the graph of Beethoven's first movement (Example 10a) might compare with Figures 1 and 2. I have put all three of these together in Figure 3, and added some of the labels for the fundamental structure which we discussed earlier.

Activity 15

Look carefully at Figure 3. What does it say about the relationship between sonata form and voice-leading structure?

Answer

Discussion

Figure 3 points out several things about the connections between the voice-leading analysis and other ways of describing sonata form.

-

The divisions between sections (exposition, development, and so on) do correspond to important features in the graph.

-

The form works around structural movement in the bass from I to V to I again. This may involve an actual modulation to the dominant (as in the exposition), or it may not (as in the recapitulation).

-

the fact that sonata form is (in one respect) a two-part structure, involving a break (and normally a repeat) at the end of the exposition, means that the fundamental structure of the graph has also to be divided into two, rather like the interruptions we looked at in OpenLearn course AA314_2 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

There are some features of Figure 3, however, which suggest that this cannot be the way that voice-leading works in every sonata-form movement. For one thing, thinking of the description of the fundamental structure at the beginning of this course, there is no place for an initial ascent here (the primary tone is the first note of the symphony), and no structural coda either, since the final tonic chord is simply repeated after bar 364. For another thing, the prolongation of ![]() in a

in a ![]() fundamental line could not carry on over the break in the form at the end of the exposition in a major key, because the

fundamental line could not carry on over the break in the form at the end of the exposition in a major key, because the ![]() cannot be harmonised by the dominant chord. And for a third thing, sonata form movements in a minor key, as you know, frequently end the exposition in the relative major and not the dominant, and so in these cases, the bass movement would have to be different.

cannot be harmonised by the dominant chord. And for a third thing, sonata form movements in a minor key, as you know, frequently end the exposition in the relative major and not the dominant, and so in these cases, the bass movement would have to be different.

For these reasons, we need to be aware that there are innumerable different ways in which a voice-leading background graph might fit within a sonata-form movement. And indeed, analysis of many different works shows that different ways of handling the harmonic structure of a sonata-form movement make the principle means by which composers achieve the tremendous variety of approaches to this form that we know from the thousands of different movements that share sonata form. As with Beethoven's Eighth Symphony, significant divisions of the sonata-form scheme nearly always correspond with harmonically important moments. But the exact disposition varies a lot.

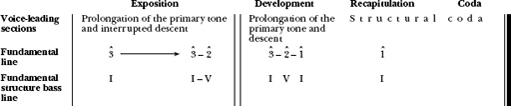

Let's look at a few examples. Figure 4 shows a typical way in which the voice leading of a sonata-form movement may work.

This is a very common scheme, and is perhaps the most obvious way of identifying the background of two of the three major-key first movements from Mozart's piano sonatas which you studied in OpenLearn courses AA314_1 and AA314_2 (K309 and K333). In both cases, the ![]() of the interrupted descent in the exposition corresponds to the beginning of the second subject. The third work whose first movement we looked at in detail there, K545, is also very similar in design. In this movement, though, the recapitulation has a most unusual beginning, where the first subject returns in the subdominant key (F major). At a background level, this forms part of the structural descent, so that the

of the interrupted descent in the exposition corresponds to the beginning of the second subject. The third work whose first movement we looked at in detail there, K545, is also very similar in design. In this movement, though, the recapitulation has a most unusual beginning, where the first subject returns in the subdominant key (F major). At a background level, this forms part of the structural descent, so that the ![]() of the fundamental line (F) appears at this point.

of the fundamental line (F) appears at this point.

One feature of Figure 4 which deserves comment is the way that the fundamental structure is split into two, so that the movement to the dominant at the end of the exposition corresponds to a move to ![]() in the fundamental line. The term for this sort of structure is ‘interrupted form’, since the structure is interrupted at the double bar, and so repeated in the second part of the movement. You saw some smaller examples of interruption at the end of OpenLearn course AA314_2, including the first eight bars of the rondo from K333 with which we opened this course (Example 4). As a background feature, it is frequently used on this very large scale as part of the patterning of an entire sonata-form movement.

in the fundamental line. The term for this sort of structure is ‘interrupted form’, since the structure is interrupted at the double bar, and so repeated in the second part of the movement. You saw some smaller examples of interruption at the end of OpenLearn course AA314_2, including the first eight bars of the rondo from K333 with which we opened this course (Example 4). As a background feature, it is frequently used on this very large scale as part of the patterning of an entire sonata-form movement.

Here is another possible way in which voice leading and formal sections may coincide. Let's imagine a descent from ![]() to

to ![]() this time.

this time.

Activity 16

Consider the three examples of background voice-leading schemes and sonata form (Figures 3, 4 and 5). What do the differences between these schemes imply about different ways of balancing the component parts of a sonata-form movement?

Answer

Discussion

The main difference between Figures 3, 4 and 5 is the weight given to the development, recapitulation and coda. In Figure 3, it is the coda that gives the balancing closure to the harmonic structure of the movement. The coda is obviously very important, and is quite substantial in length (73 bars out of 373, or 20 per cent of the movement) as is typical of Beethoven. In Figure 4, on the other hand, more weight is given to the end of the recapitulation, where the repeat of the second subject in the tonic key leads to the completion of the motion of the harmonic structure. The coda may still be an important section, but its harmonic function is slightly different. Finally, Figure 5 shows a scheme where the development section is much more important to the structure, and where it closes with a dominant chord (normally a dominant pedal) which has such weight within the form that it decisively moves it on, so that the return of the first subject at the opening of the recapitulation completes the harmonic journey of the movement.

Whilst this is, admittedly, rather an unlikely scheme for a sonata-form movement, there is a famous analysis by Schenker himself of the Finale of Beethoven's ‘Eroica’ symphony (although this particular movement follows a rather different formal plan) in which the decisive structural cadence is placed similarly early on, at bar 277 of a 473-bar movement.

Finally, let's look at one more scheme, which describes a typical minor-key movement.

This outline is different from that in Figures 4 and 5 in that it does not show an interrupted form, but shows instead how the modulation to the relative major (degree III of the scale) can still support a prolongation of ![]() (or

(or ![]() ) in the top voice of the background level of the form. It also shows the importance that the dominant degree, which often forms a pedal at the end of the development section, may have. Although there may not be a modulation to the dominant key area in the whole movement, the dominant degree will still be crucial to the way that the form is constructed.

) in the top voice of the background level of the form. It also shows the importance that the dominant degree, which often forms a pedal at the end of the development section, may have. Although there may not be a modulation to the dominant key area in the whole movement, the dominant degree will still be crucial to the way that the form is constructed.

These four examples, although abstract, indicate some of the huge variety of ways in which composers make the harmonic outline of sonata form work. There are countless other ways in which a voice-leading fundamental structure may correspond to the categories of sonata form. The thing to bear in mind, when you read an analysis of this kind (as of any sort), is that form in music is not a rigid set of procedures that happen the same way in every piece. Although the fundamental structure at the background of the voice leading is a very simple piece of counterpoint, and is indeed shared between almost all tonal pieces, the whole point of an analysis is to show how this simple background structure gives coherence and meaning to the complex and intriguing design at the foreground of the music. Such an investigation should only deepen our appreciation and respect for an expert such as Beethoven.