2 Defining race

In order to begin to answer the question ‘what is race?’, we need to start with a general idea of what we’re investigating. You’ll start by looking at a dictionary definition, which can be a useful starting point for getting a grip on how people ordinarily understand the meaning of a term.

Activity 1

1. Using a search engine or a physical dictionary, find a dictionary definition of race and enter it in the box below. The word ‘race’ has several different meanings, such as a competition to see who is the fastest, so make sure you select a definition that refers to a way of categorising humans.

2. Does this definition sound about right to you? Does it match (or roughly match) what you think you mean when (or if) you talk about race? If not, what would you change?

Comment

In one dictionary, race is defined as ‘any one of the groups that humans are often divided into based on physical traits regarded as common among people of shared ancestry’ (Merriam-Webster.com, 2023). Under this definition, race refers to groups based on shared physical traits (such as skin colour, eye colour, hair texture and so on). These shared physical traits are believed to be an indicator of shared ancestry (or descent). You may think that this definition captures how a lot of people think about race.

Dictionary definitions can be a starting point for understanding the meaning of a term, but often they don’t exactly match what philosophers mean by the term. Below is a definition of ‘race’ given by the philosopher of race Joshua Glasgow. This definition is what Glasgow thinks people usually mean when they talk about race. Glasgow is an American philosopher, and he restricts this definition for what people mean in the United States (US). This definition might sound familiar to you in your own social context, or it might be a bit different.

Races, by definition, are relatively large groups of people who are distinguished from other groups of people by having certain visible biological traits (such as skin colours) to a disproportionate extent.

This definition is similar to the definition found in the Merriam-Webster dictionary. However, there are some differences. Glasgow’s definition doesn’t include any mention of shared ancestry – it only specifies that racial groups are distinguished by (generally) shared biological (physical) traits. This seems to match the way that people use or think about race in many places – for example, people often make judgements about what race someone is based on visible physical characteristics (for example, skin colour or facial features). Glasgow’s definition also specifies that races are ‘relatively large groups’. This also seems to reflect how race is used, at least in some places – for example, several national censuses that collect data on race list approximately five racial categories.

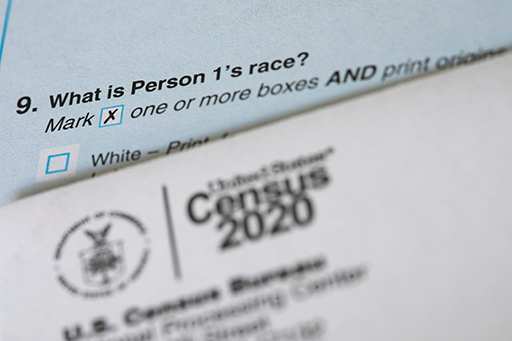

For example, these are the five racial categories listed on the 2020 US census:

- White

- Black or African American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

You might not be entirely satisfied with Glasgow’s definition, but it at least gives us a starting point for investigating race. Do racial categories, understood as relatively large groups distinguished by differences in physical characteristics, correspond to real differences in the world? If so, what sorts of differences do they correspond to? Are they biological? Are they social? These are the questions that philosophers doing metaphysics of race are interested in, in order to figure out the fundamental nature of race.