4.1.6 Real interest rates

You will recall from Week 2 that it is important to take inflation into account when managing your finances. In Week 2 you looked at the distinction between nominal and real income, the latter taking into account the level of price inflation. Now you do the same in looking at interest rates.

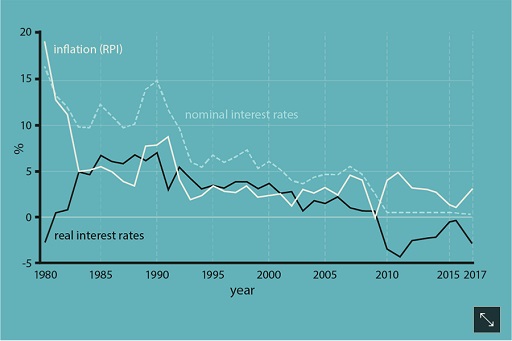

Real interest rates are interest rates that have been adjusted to take inflation into account. Looking at the graph, you’ll see that when inflation is higher than the nominal interest rate, real interest rates are negative (as they were in 1980/81 and again from 2010). Real interest rates are at zero when the rate of inflation and the nominal interest rates are the same; and they are positive when the nominal interest rate exceeds inflation.

Real interest rates were low in the 1990s and 2000s, falling from 7% in 1990 to just under 2% by 2004. Subsequently they fell further. By 2013 the fall in the (nominal) official interest rate to a historical low of 0.5%, combined with price inflation of 2.7%, resulted in negative real interest rates of -2.2%.

So, if you earn a nominal rate of interest of 1.5% on your savings and price inflation is 2%, you are actually getting a real interest rate on your savings of -0.5% – a negative rate of return. Such a situation where real interest rates are negative is clearly adverse for savers. However it is good news for borrowers if the cost of borrowing is negative in real terms.

Unsurprisingly, the low interest rates offered on savings in recent years have encouraged some households to reduce their debts – particularly credit card debts which have relatively high interest rates – by reducing their savings balances.

Most mainstream lenders link interest rates, including mortgage rates, to the official rate of interest, and so the cost of debt, including mortgage debt, declined over this period. This is another reason why debt levels may have risen in the 1990s and until 2007.

After 2007 the relationship between the official rate of interest and the cost of debt products was altered by a widening in the margin between them. Nevertheless, in the mid 2010s interest rates on mortgages and many other debt products were historically low.