10 How do people know about the past?

We can learn about the past by using different types of evidence and sources. You could, for example, read a specialist book written by a historian. This will have been written after the event. It will use selected evidence and will provide a commentary and the views of the author. Such a book is called a secondary source.

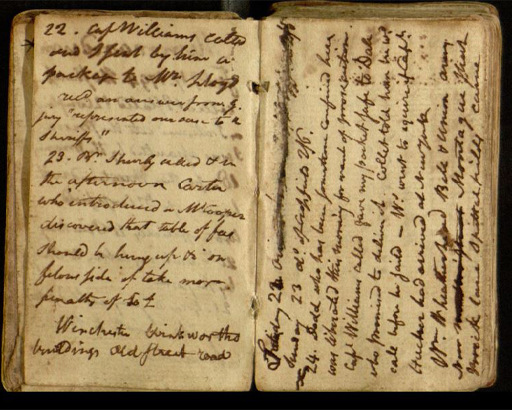

To write secondary sources, authors study primary sources. These are materials created during the period being studied. They might include official reports, accounts of what was said in Parliament, correspondence or diaries from the time. Other primary sources might be newspaper reports, posters and images (for example, drawings of prisons or prisoners). From the 1820s, prison chaplains and inspectors began to keep records of what was being taught in prisons and how it was taught. These records are useful primary sources for the topic you are studying now.

However, just because a source was written at the time does not mean it is necessarily ‘true’ or unbiased. When writing accounts people contradict themselves, omit, interpret or even lie. They also write with a specific purpose in mind. Take, for example, the accounts of prison reformers such as Elizabeth Fry and members of the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline, who provided many descriptions of the squalor and misery they found in British prisons. Officials such as governors, chaplains and magistrates who were in charge of prisons often countered these with declarations of their good management and care of prisoners. Historians now acknowledge that both groups were selective in their descriptions of imprisonment in order to make their case for and against reform.

When looking at any sources (primary or secondary), try to assess the purpose, values or motive of the author. Perhaps you can see where the author has been selective or remained silent? Maybe you can make a judgement based on a comparison with another source, such as another prisoner’s diary, another article from a different newspaper, or another history book on the same topic.

Activity 4 Using a source

Part 1

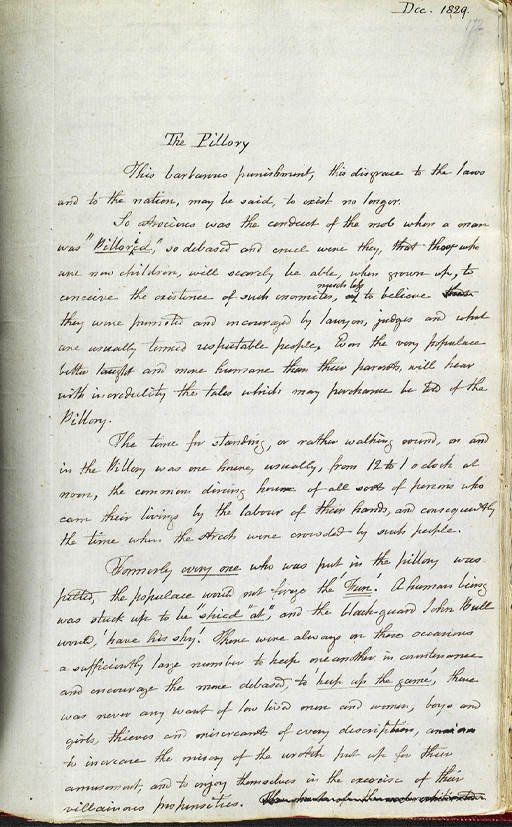

Write a list of questions that you might ask to assess the relevance and value of a written source. You might find it helpful to use the source shown in Figure 13 as inspiration.

The pillory

This barbarous punishment, this disgrace to the laws and to the nation, may be said to exist no longer.

So atrocious was the conduct of the mob when a man was “pilloried”, so debased and cruel were they, that those who are now children, will scarcely be able, when grown up, to conceive the existence of such enormities, much less to believe they were permitted and encouraged by lawyers, juries and what are usually termed respectable people. Even the very populace better taught and more humane than their parents will hear with incredulity the tales which may perchance be told of the pillory.

The time for standing, or rather walking round, on and in the Pillory, was one hour usually, from 12 to 1 O’Clock at noon, the common dining hour of all sorts of persons who earn their livings by the labour of their hands, and consequently the time when the streets were crowded by such people.

Formerly every one who was put in the pillory was pelted, the populace would not forgo the “fun”. A human being was stuck up to be “shied at”, and the blackguard John Bull would “have his shy”. There were always on these occasions a sufficiently large number to help one another in countenance and encourage the more debased, to “help up the game”, there was never any want of low lived men and women, boys and girls, thieves and miscreants of every description, and to increase the misery of the wretch put up for their amusement, and to enjoy themselves in the exercise of their villainous propensities.

Discussion

Here are some questions, but this is not an exhaustive list. You may have thought of other ones. When you come to look at sources in other sessions you might want to refer back to these questions. Note that a source might be a document or an image or a history book or a novel. You can ask similar questions of any of these.

- When was it written or produced? Knowing this tells us whether the source is a primary source (written at the time) or a secondary source (written later by someone who did not live through the event). Dates on primary sources allow us to gauge how close the author was to events they were describing, and to place the source in the context of other things that were happening.

- Who is the author? This is important because it can help us understand their motivation. For example, knowing that the author was a middle-class female Christian prison visitor might help you to understand some of their presumptions and motives.

- Is there anything in the text which tells you why the author wrote this? What was at stake for this author?

- Is the author making a specific argument, for example, for prison reform, or against the teaching of reading in prisons? Might they have selected evidence to support their case?

- Does the author employ emotive language? Do they use seemingly neutral information?

- How does this text compare to others on the same topic?

- Who is the intended readership of this source?

Part 2

Return to any notes you made about the video in the Introduction to this session and see if you want to change them in the light of what you have read. Try to summarise the different approaches to the history of the prison outlined in the video.

Discussion

In the video three different approaches to the rise of imprisonment are outlined.

- One focused on the roles of reformers who had successfully argued for prison as an alternative to hanging. Although corporal punishment, such as the use of the lash, continued throughout the 1800s, transportation ceased, prisoners were clothed and fed and were not required to pay for their own accommodation.

- Another approach was to see reform not as a triumph of humanity but as a way to promote stability and order, to mould prisoners through disciplining their minds and bodies. Prisoners could be observed, categorised, and controlled through hard labour and the use of Christian observance to promote obedience.

- A third perspective examined the implementation of these ideas at the level at which people lived their lives. Across the UK there was a lack of uniformity and consistency regarding treatment and perspectives. While some politicians and governors focused on keeping order, not all of them achieved this goal or saw it as their main aim. Developments were determined by trial and error and individual passion as well as based on data derived from studying prisoners.