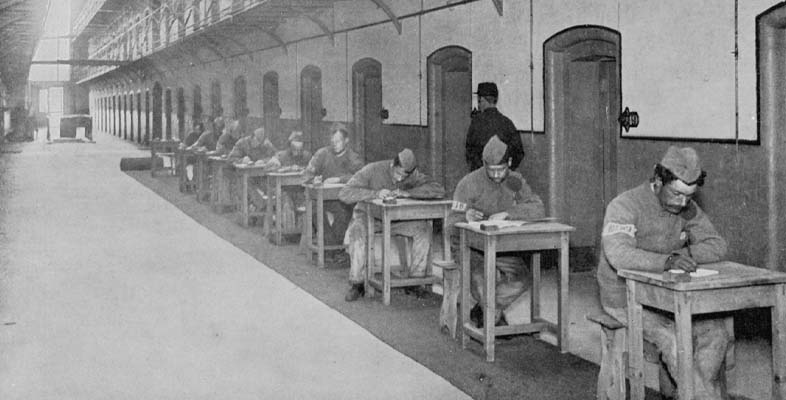

Session 6: Education in a changing penal regime

Introduction

During the 1850s, ‘the reformatory objective in penal policy underwent an almost total eclipse’ (McConville, 1981, p. 347). Doubts were expressed about whether imprisonment could reform convicted criminals and, increasingly, about whether prisons should even try to do so.

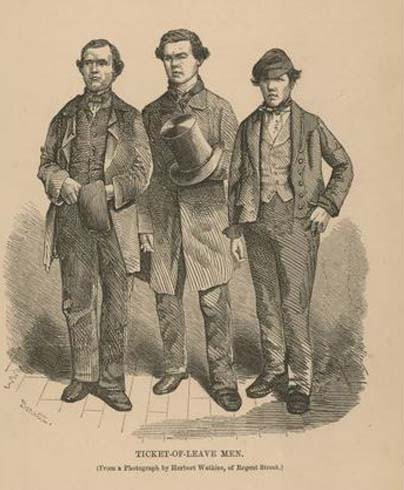

By the mid-1860s, new legislation had been passed and penal policy had been reformulated with the aim of ensuring that prisons were places of punishment, which brought habitual criminals under control and which deterred any would-be offenders.

Yet, despite this, education continued to be delivered in prisons. The proportion of prisons with schools continued to rise. The curriculum in many ways was expanded and secularised. Education, in other words, became more deeply entrenched in the penal regime.

This session looks at why and how this happened. First, you will examine the reasons for growing disillusionment with reformatory projects and the increasing emphasis on punishment in the penal regime. Next, you will explore the reasons behind the retention of education. The remainder of the session will look at the impact of policymakers’ desire to punish and deter on teaching and learning inside prisons, including the extent to which the transformative potential of education was undermined.

By the end of this session, you should be able to:

- outline the reasons for a change in penal policy during the 1860s

- explain why education continued to be provided in prisons, and how the desire for a more punitive regime affected its delivery and potential results

- understand the use of Standing Orders in the convict prison sector after 1850

- compare and contrast two primary sources.