3 Prison in the 1700s

Prisons have existed for centuries in the British Isles. In the 1700s, in all four nations, prisons were run by local authorities, mainly by those in charge of counties, boroughs and parishes, but also by universities and even cathedrals. There were different types of prison. Lock-ups temporarily held those who had been arrested for crimes and were waiting to see the magistrate, as well as drunks who needed to sober up. Gaols were used for prisoners on remand. Bridewells, or Houses of Correction, were for those convicted of petty crimes – vagrants, prostitutes and drunks – where efforts were made to correct their behaviour.

Prisons were not just for those accused and convicted of crime. Children were often imprisoned with their mothers, or some for their own crimes. Across Britain, over half of people in gaols were debtors. Another significant category of prisoner was those deemed a threat to the state for political reasons. After the 1715 and 1745 rebellions in Scotland, the prisons were filled with political prisoners and in 1794 habeas corpus (an arrested person’s right to a trial) was suspended. This enabled people to be held without trial indefinitely.

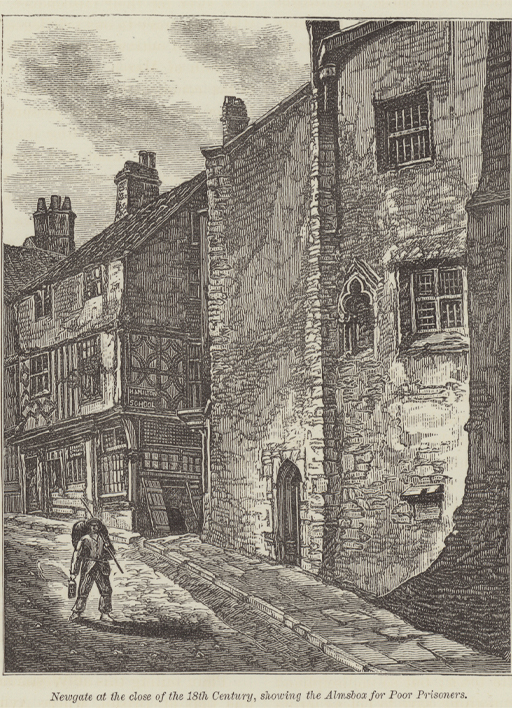

Many prisons in the mid-1700s were pit-like castle dungeons. Prisons had no heating, no bedding and little access to running water. Sanitation was rudimentary. There was no segregation of women and children from men. Often the ventilation was poor and prisoners were chained to one another. There was little to do and prisoners frequently had access to alcohol. There were many cases of contagious diseases, notably gaol fever, a form of typhoid. Gaolers were typically unpaid officials who made their money by extracting fees from prisoners – for necessities such as food and bedding, and even for release.