3 The role of religion

Concern about the morality of the education that prisoners received also put some limits on the expansion of the curriculum. Education was meant to be ‘reformatory’ – to make convicted criminals into better people. Prison education was not about giving men, women and children particular skills to enable them to get jobs. Instead, it was thought that better people – made so through Christianisation and the civilising effects of literacy and numeracy – would make better workers.

Earlier, you looked at how prison chaplains were collecting evidence to prove that a lack of Christian knowledge and belief was the cause of rising crime rates. By the 1840s, chaplains had firmly taken charge of education in prisons, at least in England and Wales. Supported by new rules and regulations for local prisons, chaplains directed the course of instruction, frequently attended schools to supervise the teaching, and regularly examined the progress made by prisoners.

Some chaplains welcomed the addition of secular subjects to the curriculum. The assistant chaplain at Millbank Penitentiary in 1839 explained that since the convicts had been exposed to ‘useful secular knowledge, their minds and tempers have certainly appeared to him to be in a more elastic and altogether healthier state – a state of mind which may be deemed generally favourable to their spiritual advancement’ (Inspectors, Home District, 4th Report, 1839, p. 97). For similar reasons, prison inspectors encouraged chaplains at local prisons to make their curriculum ‘a little more secular’.

However, there were limits. Captain Williams, the Northern District inspector, described education at Lancaster County Gaol in 1842 as too narrowly confined to reading and writing. While the prisoners were reading well and forming letters perfectly on slates, they were entirely deficient in religious knowledge (Inspectors, Northern & Eastern, 8th Report, 1843, p. 83). At Wakefield House of Correction in 1845, the chaplain suspended the teaching of writing and arithmetic because he thought the prisoners were ‘careless and inattentive’ during religious instruction, and interested only ‘in obtaining information on secular subjects, with a view of bettering their temporary condition, and making the time pass more easily’ (Inspectors, Northern & Eastern, 11th Report, 1846, p. 42). The study of geography and history were often limited to knowledge which aided the study of the Scriptures. Chaplains at Lewes and Fulham convict prisons ensured that Christianity pervaded every lesson taught in the prison school.

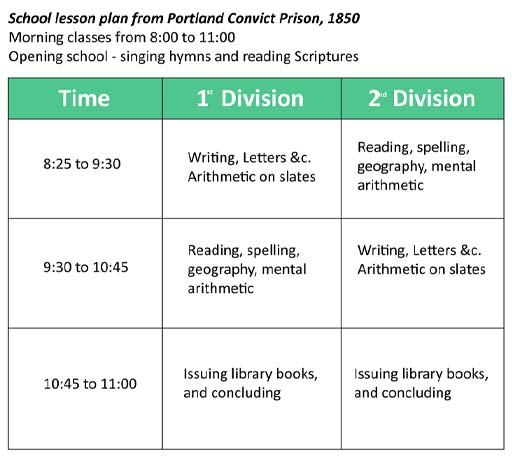

Activity 2 Lesson plans

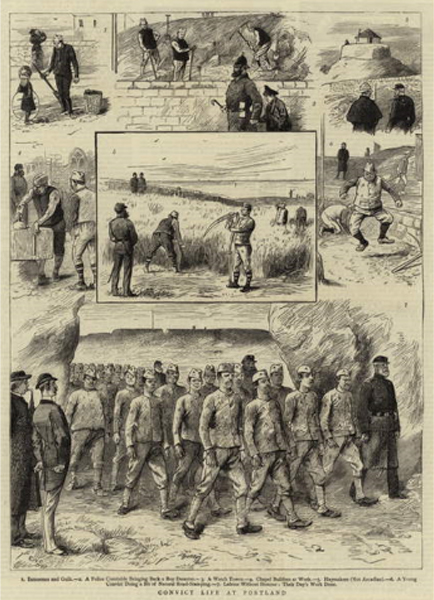

In 1850 there were, on average, about 800 convicts on any given day at Portland Convict Prison for men. All the convicts were enrolled in the prison school. They were divided into 11 classes, and each class was excused from labour to attend school for half a day (or three hours) each week. The classes were taken sequentially, starting with the first on Monday morning and ending with the 11th on Saturday morning. Each class was further sub-divided into two groups.

Here is a copy of the school lesson plan for the morning class each day. The lesson plan for the afternoon class was identical, except that the school was held from 12.30 to 15.30. Look at the plan now, and try to answer the following questions:

- What conclusions can you make about the lessons and the time devoted to each activity?

- Are there any activities, or terms, which look unusual?

Discussion

You may have been struck by the amount of time – 25 minutes – that was devoted to singing hymns and reading Scriptures at the beginning of the lesson. Considering that convicts had only three hours a week at school, and that they also attended services in the chapel on Sunday and read prayers every day, this was a lot of time to take from teaching other lessons. It shows how important religion was in the school curriculum.

Another 15 minutes at the end of school was taken up with the exchange of library books, again, eating into valuable time for teaching and learning. You will look at prison libraries in Session 4.

Did you notice the term ‘Letters’? Prisoners in convict prisons and in some local prisons were allowed to send letters home at various stages during their imprisonment. In order to supervise their composition, and assist those who could not write, letter writing was done during school time. Although it was another activity which consumed valuable time, it could also be used as a way to teach writing. In 1859, the chaplain at Chatham Convict Prison wrote that although ‘their school exercises are more or less interrupted … by writing letters to their respectable friends … such writing should tend in a measure to improve both their composition and their penmanship’ (Director of Convict Prisons Report, 1860, p. 244).

Another term in the plan which might be unfamiliar is ‘slates’. Slates were essentially mini blackboards. Chalk or pencil was used to write on slates, and anything written on them could be rubbed out. Slates were common in elementary schools in the 1800s because they could be reused and so were cheaper than paper and ink. However, students who learned to write on slates found it difficult to move to paper and ink, as prison teachers and chaplains soon discovered. Despite this, slates persisted in prisons because of the need to limit any form of illicit communication. Paper could be secreted and taken away. Slates could be monitored and any writing easily erased.

You have ventured into a discussion of method – how prisoners were taught. Now, you’ll explore that further.