4 Drilling and memorisation

When prison officials were establishing schools, they looked for guidance on how to teach reading, writing, arithmetic and other subjects from educational experts outside the prison. Until the imposition of silence and separation in the 1830s, the monitorial system, a method of instruction popular in elementary schools, was adopted in several prisons, including Millbank Penitentiary, Brixton House of Correction and Chester City Gaol. Prisoners requiring instruction were taught in small groups by monitors (fellow prisoners) who received their instructions on what to teach from the schoolmaster or mistress. Even after silence and separation prohibited the use of monitors, the core method of instruction remained much the same.

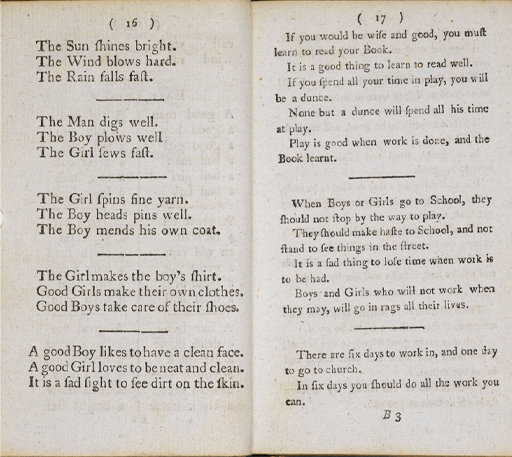

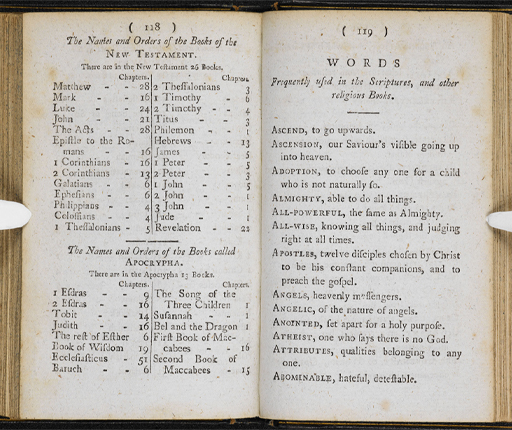

The monitorial method relied on drilling and memorisation. Language was broken down into a series of discrete units, or stages, each of which had to be mastered before the student could advance. Students began with the letters of the alphabet, which had to be learned by name (not sound); next they began the process of joining two letters; and then they advanced through words of one syllable, then two, and three, until they could master words with any number of syllables. At the same time, students were required to memorise the Lord’s Prayer (a Christian prayer recited during church services) and the Catechism (a set of questions and answers affirming someone’s belief in Christianity and commitment to the church). When they had reached polysyllabic words, they began to read, and commit to memory, passages from the New Testament (Vincent, 1989, p. 77).

Writing was sometimes taught after progress in reading had been made; at other times it was taught alongside reading. After instruction in basic penmanship, students were put to work ‘making copies’ – writing out chunks of text, often religious, which were either displayed on a blackboard or, to test spelling, dictated by the teacher. In order to ensure that students understood what they read and wrote, they were tested by question and answer, a method otherwise known as being ‘catechised’.

These methods of instruction were bolstered by the use of popular school textbooks in the prison, such as Mrs Trimmer’s Charity School Spelling Book. Written in the late 1700s it featured alphabets for copying, spelling lessons, and moral lessons about the godly and the ungodly told in words of one syllable. Reading lesson books published by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, the Sunday School Union, and the National Schools Society were also used. Readers and spelling books specifically designed for adult learners were purchased for use in convict prisons. Prisoners navigated the Bible, and were ‘catechised’, with the help of Albert Judson’s Questions on the Holy Scriptures, Matthew Henry and Thomas Scott’s Commentary Upon the Holy Bible, and Sarah Timmer’s Lessons on Scripture History.

The convict prison chaplains also approved the acquisition of schoolbooks to support lessons in history and geography. Again, the titles and content of these books reveal the emphasis that was placed on the acquisition and recitation of facts. For example, women at Brixton Convict Prison made use of Wilson’s Catechism of Modern History and Wilson’s Catechism of Geography. Gleig’s School History of England, which contained a chronology, tables of sovereigns and questions for examination, was popular at male convict prisons (Crone, 2022, ch.4).

Activity 3 Case study: Reading Gaol

In 1840 the new chaplain at Reading Gaol, the Rev. John Field, campaigned for the introduction of the separate system. The county magistrates, who were in charge of the prison, agreed and a new prison, resembling a medieval castle, was built in its place. The building survives, although the prison was closed in 2014.

From 1844, prisoners who arrived at the new gaol were confined in separate cells. They were given no work, and if they asked for something to do they were given a Bible to read. If they could not read the Bible, the schoolmaster was sent to their cell to teach them. All the male prisoners attended school in the partitioned chapel as well. Female prisoners were excluded from school because of the burden of the prison laundry, but by the late 1840s attempts were made to give them some instruction too.

Field’s scheme was based on the memorisation of passages from the Bible. If a prisoner could successfully recite the lessons he had learned, he was given labour in his cell – typically oakum picking (picking out the fibres from old rope) – for ‘relaxation’. Field believed that rote learning could turn prisoners into non-offending Christians. The county magistrates in charge of the prison thought that rote learning was a form of punishment more irksome than some types of hard labour (Crone, 2012).

Prisoners who could read and who had shown evidence of reformation were either taught, or allowed, to write. Field asked these men to complete examinations to test their learning. Below is a copy of one of the examinations completed by I.N., a prisoner who had, at this stage, been imprisoned for three months. Field set a question, and then asked I.N. to respond using what he had learned in the prison.

Some prisoners at Reading Gaol were entitled to send letters home. This one was written by J.I., who was sentenced to 18 months imprisonment, to his sister, in February 1848. Read it and compare it with the exam script above it.

Now read and compare I.N.’s exam script and J.I.’s letter using the following questions:

- What similarities stand out?

- Can you spot any differences?

- Both were written by prisoners – how authentic are they?

- Are these the voices of prisoners?

Exam script

Give reasons why we should not frequent the public house:

- Because we can get no good there. Luke xi. 4.

- Because we should not go into bad company. Psalm i. 1. 1 Thess. v. 22. Proverbs i. 10.

- Because we should not set a bad example. Luke xvi. 28. James iv. 17. Psalm cxl. 11.

- Because we can employ our time better. Ephes. V. 15, 16. Titus ii. 11, 12. 2 John xi. 11. Psalm xc. 12.

- Because we shall have to render a strict account of our lives at the day of judgement. Luke xvi. 2. Proverbs xxix. 1. Eccles. iii. 15, 17.

- Because we should not encourage drunkenness, folly and vice. 1 Cor. vii. 31. Psalm ix. 17. Proverbs iv. 14, 15.

Letter

The particular [sin] is drinking, which brought me very low; and if you read the following verses, you will see that I have proved them. Prov. xx. 1; Prov. xxiii. 21 & 32; Haggai. i. 6; Prov. i. 31; Prov. xiii. 15-21; Prov. xi. 21; Isaiah xlviii. 22; Jer. xxii. 21. And now my dear sister, seeing I have proved this, I do heartily pray that you will correct your son betimes, and he will give you comfort and joy … if you read the following Scriptures, you will see that your thoughts cannot stand. Ezekiel xviii; Colos. iii. 25; Mark xvi. 16; Luke xii. 3 & 5; Psalm ix. 17; Psalm xi. 6. This shows us plainly that all who don’t repent must suffer the vengeance of eternal fire. Read St John’s gospel, and there you will see that Jesus died for sinners.

Discussion

Comparing the exam script and the letter, the first thing you may have noticed was that both contained references to parts of the Bible – that is, specific chapters and verses. This emphasises the importance of the Bible in the instruction given at Reading Gaol. You might have also been impressed that both men were able to recall specific passages to support particular points. This shows how rigorous drilling and memorisation was at Reading Gaol. Both made reference to the sin of drinking alcohol, and its relationship to criminal behaviour. It is clear that Field was attempting to train them to avoid the pub when released from prison.

You may have thought that the main difference between the two texts was that the letter warns that those who do not mend their ways will not only end up in prison (like J.I.) but will ‘suffer the vengeance of eternal fire’. In other words, they will go to hell, unless they repent and believe in Christ.

Were these authentic voices of prisoners? The first was written under exam conditions, and I.N. obviously wanted to show that he had learned something at the prison school. J.I. would have known that his letter would be read by the chaplain before it was sent to his sister. Both prisoners might have hoped that by showing Field they had reformed that they might gain something. Indeed, Field had, in the past, argued for the early release of prisoners who had performed well under his scheme, so this could have motivated the authors of these sources.

Alternatively, you could argue that the methods of instruction used in the prison – drilling, memorisation, writing copies – meant that these prisoners, when given pen and paper, were hardly equipped to write anything else. J.I. in particular would not have wanted to pass up the opportunity to write to his sister. In 1850, when prison inspector Captain Williams interviewed prisoners at Reading Gaol about the instruction they had received, he found they could repeat verses from the Bible perfectly but did not understand the meaning of what they had learned (Inspectors, Home District, 15th Report, 1851, p. 63).

Finally, it is important not to underestimate the message of hope contained in the Bible. Instruction focused on soul-saving. Many of these men would not have wanted to return to prison and they were being told they would not have to if they could live as good Christians. Reality of life outside the prison may have suggested otherwise, but it does not mean these prisoners were not sincere when they wrote these pieces.