1 Books behind bars

An alternative form of education and self-improvement in the prison was provided through access to books and time to read them. Deliberate schemes to provide prisoners with books date to the early 1700s.

In 1698, an English clergyman, Thomas Bray, established the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) to spread Christianity through the distribution of Bibles and religious tracts (small books or pamphlets) in Britain and abroad. In 1702, the SPCK began to supply Newgate Gaol with Bibles, prayer books and tracts. Soon after, the SPCK sent a packet of tracts to every county gaol in England and Wales (Fyfe, 1992, pp. 3–6).

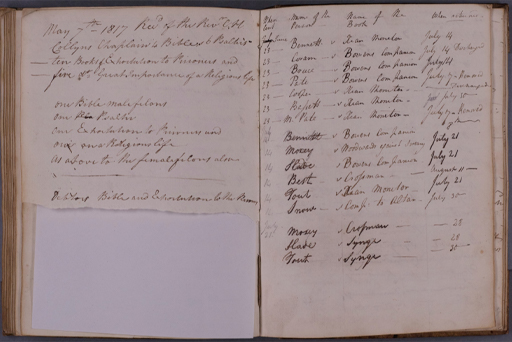

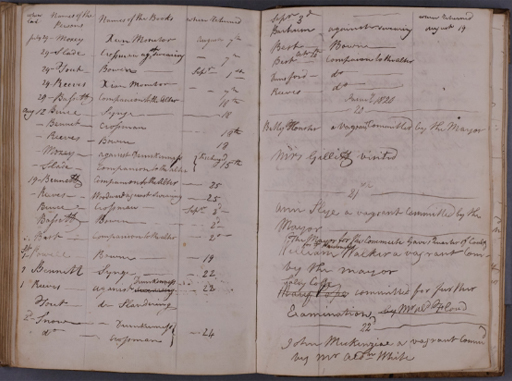

As the number of paid prison chaplains grew and interest in soul-saving in prisons expanded, there was a greater demand for appropriate reading matter for prisoners. The 1823 Gaols Act gave prison chaplains in England and Wales authority over the acquisition and distribution of books (Gaols Act 1823, section 30).

Governors, in their annual returns to the Home Secretary, had to declare whether prisoners were supplied with Bibles and other books. Rules for the new Penitentiary at Millbank stated that the chaplain should be supplied with books from the SPCK and that he should distribute them among the prisoners as he saw fit. The SPCK continued to be the main supplier of books and reading matter for local prisons in England and Wales. Sometimes the SPCK sent packages of tracts for free, other times the prison authorities paid for them. By the 1830s, there were very few prisons at which prisoners did not have access to Bibles, prayer books and religious tracts.

Often chaplains distributed the books freely among prisoners. They handed out copies of tracts to individuals on arrival, or they left tracts, Bibles and prayer books in the day rooms for prisoners to pick up and read. According to the chaplain at Horsemonger Lane Gaol in 1832, prisoners were well supplied with religious books: many read them, some neglected them, and others tended to destroy them (Gaol Act Reports, 1833, p. 242).

Tracts were often flimsy publications which could fall apart if passed through many different hands. There are many examples in the primary sources of prisoners using pages torn from Bibles to roll tobacco, to make playing cards, and to curl their hair. Several chaplains restricted the supply of religious books to prisoners who requested them and promised not to mutilate them.

Activity 1 Bible reading at Reading Gaol

Part 1

You looked at the regime established at Reading Gaol in the mid-1840s in Session 3. Using the knowledge you acquired then, read the following extract from the journal kept by the prison governor which was included in the 1845 report of the Home District inspectors of prisons and try to answer the following questions:

- What do you think the prisoners were reading?

- What evidence is there to suggest that they were enthusiastic readers?

- How might we interpret the prisoners’ enthusiasm for reading?

March 16th 1845. – I went through the male prison at 7.30pm, and looked in upon every prisoner through the inspection slides, 97 in number, and found them all reading but 12, ten of whom were walking about, and two warming their hands over the gas light; … [I] have made numerous similar inspections of prisoners at all hours, and have invariably found about the same number in proportion reading.

Discussion

- The prisoners observed by the governor were most likely reading the Bible. You might remember from Session 3 that prisoners arriving at Reading from 1844 were given Bibles to read when they asked for work. Alternatively, some of these prisoners might have been reading other religious books – prayer or hymn books, or maybe tracts. The Rev. John Field liked to give prisoners a copy of an SPCK tract, The Divines of our Blessed Lord, as well as one authored by himself: Friendly Advice to a Prisoner. Secular (non-religious) books were rarely distributed to prisoners at Reading Gaol in the 1840s and 1850s (Crone, 2012).

- According to the governor’s account, 85 of the 97 prisoners appeared to be reading. It is possible that the 12 men who were not reading were taking a break from reading, to warm their hands or to exercise. It is also possible that the 12 men could not read (i.e. they had not yet learned how to read).

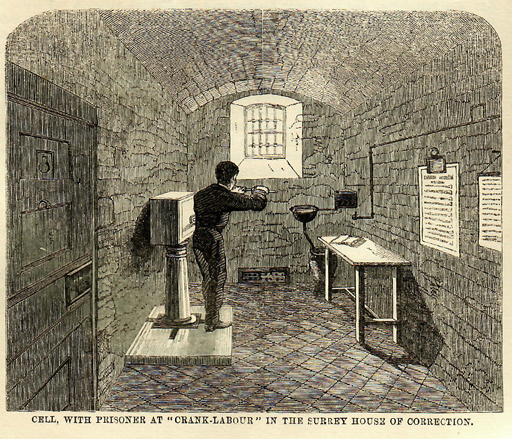

- You might have remembered from the activity in Session 3 that Reading Gaol had recently been rebuilt to allow for the separate confinement of prisoners. There was a hint in the extract – the governor observed each man using the ‘inspection slide’. The men spent most of their time in cells by themselves. They might have:

- felt able to pick up the religious books left for them without having to suffer the jeers of their peers

- been reading the Bible because there was nothing else to do

- heard the governor approaching and decided to pretend to read their Bibles in the hope of looking penitent and gaining some kind of reward. The source does not speculate on this, but clearly there are many reasons why the prisoners might have appeared so studious.

Part 2

Read the below statement made in 1848 by a prisoner to the Rev. John Field, chaplain at Reading Gaol. In Session 3 there was some consideration of personal testimony. What do you make of this evidence?

What a blessing it is that I was put into a cell with nothing but my Bible, and could not get away from it! For the first three or four weeks I used to take it up and throw it down again, and curse it; but I could not help taking it up; and what a blessing it has turned out! I seem to have been brought here that I might read the Bible, and now I believe it. I shall forever bless God that I was brought to this prison.

Discussion

It further illuminates the governor’s report of three years earlier and suggests that prisoners could be reformed through reading the Bible. However, this prisoner’s response has been filtered through the chaplain. We may not be reading exactly what the prisoner said and we cannot tell if the prisoner sounded sincere.