4 Censorship

Mayhew’s was one of several studies of the pernicious effect of reading fiction – especially stories about famous criminals – published in the 1840s and 1850s. The Rev. John Clay, chaplain at the Preston House of Correction, and Captain Williams, prison inspector for the Northern and Eastern District, also conducted interviews with juveniles in prisons in which Jack Sheppard was identified as a dangerous book (Select Committee on Criminal and Destitute Juveniles, 1852, pp. 406–22, 422–5). Close attention was paid to the content of stories acquired for the prison library to ensure that books were devoid of any representations of criminal activity, even when those books had been written by leading or highly respected novelists (including Charles Dickens).

Concern about the effects of reading on prisoners was not limited to the novel, or ‘crime fiction’. In 1856, a senior official in Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, the government department which supplied books to convict prisons, objected to instructions he had received from Sir Joshua Jebb, chair of the Directors of Convict Prisons, to supply Portsmouth Prison with two copies of Treatise on Law of Banker’s Cheques (a text of which there had been many editions since its publication in 1799). The official wrote:

Now one would naturally suppose that the majority of convicts know a great deal too much of the arrangement of Country and other Banks, and that the less they are acquainted with these matters and with the law of cheques, the safer private property is likely to remain.

On this occasion, Jebb successfully argued the case, and the books were subsequently dispatched to Portsmouth.

Even religious works were intensely scrutinised. The Garden of the Soul and The Poor Man’s Catechism, religious books selected for Roman Catholic prisoners, had to be published in a different edition for prisons after a prison governor objected to ‘certain passages suggesting indecent ideas’ (Fyfe, 1992, p. 84).

Even the Bible presented problems for prison officials. As early as 1828, George Holford, one of the managers of Millbank Penitentiary, expressed concern that prisoners left alone with the Bible would view it ‘merely as a storybook, to choose out such parts as shall afford him entertainment, and even to dwell upon those chapters or expressions which, in his ignorance, and with his bad dispositions, he may misinterpret into something like a sanction or precedent for his own acts of vice or folly’ (Holford, 1828, p. 160).

The prison library represented an ideal opportunity to shape common reading tastes. Through a carefully chosen catalogue, prisoners could be taught what they should read. Yet, however hard they tried, prison officials could not dictate precisely how a book should be read, nor how it should be interpreted, by the individual.

Activity 3 Accessing books in the library

The following extract is from a report by an inspector of prisons on Lancaster Castle County Gaol. It was published in 1837. Read the extract, and make some notes on the information it provides about access to the prison library.

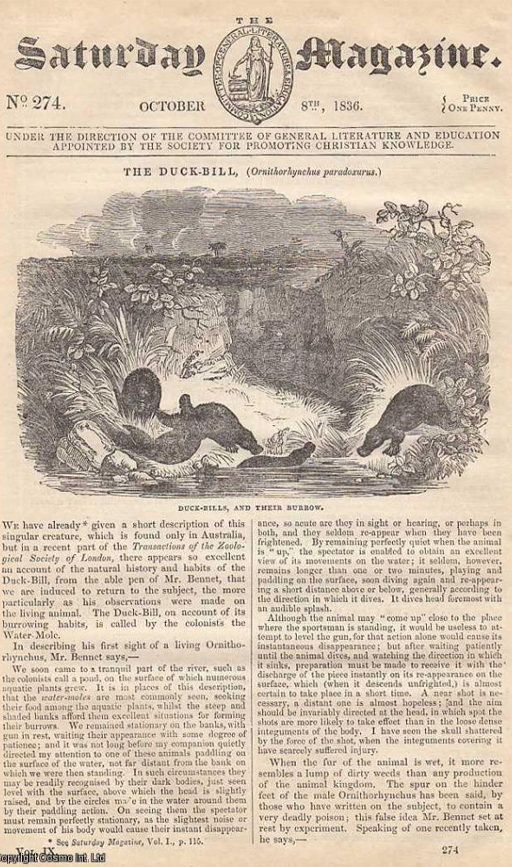

A circulating library has been formed in the prison, under the superintendence of the chaplain; it was first commenced by donations of books, but others were subsequently added by purchase: among the books are Constable’s Miscellany and others of a similar description. They are selected from a catalogue by the prisoners themselves, or at their desire by the schoolmaster, and are changed every Saturday. The usual choice is for books of a short, or entertaining character, [such] as history, voyages, travels. The Saturday Magazine is oftener called for than any other publication. The females are likewise permitted the use of the library, but are restricted to works of a religious tendency. The matron states “that the females refuse to avail themselves of the books, saying they want some of a livelier sort”.

Discussion

This short passage tells us a surprising amount about access to the library at Lancaster Castle County Gaol. Perhaps the most striking information is that male prisoners could borrow entertaining books, but female prisoners were limited to religious books.

Concern about women of all ranks of society reading fiction was expressed at various points throughout the 1800s. Women were considered intellectually weaker than men and therefore more susceptible to the dangers of tales of romance and fantasy. At the same time, female criminals were regarded as more transgressive, or immoral, than male criminals. Committing a crime was completely opposed to the image of the ideal woman. According to the matron at Lancaster Gaol, the women refused to read the religious books provided for them.

Male prisoners had their books changed once a week. According to the report, they also got to choose from the catalogue, though it is not clear what happened if their choice was not available. The report also gives us an idea of their preferences – entertaining books, history, voyages, and especially The Saturday Magazine. This was an educational magazine published by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge. It had four pages, cost a penny, and contained short articles on a range of subjects including nature, science, history, geography and technology.