3 Expanding the Criminal Returns

The search for educational data and the growing awareness of the potential utility of prisons and prisoners coincided with the reorganisation of the national criminal statistics (known as the Criminal Returns) by the Home Office in 1833 to 1834. This work initially focused on the categorisation of indictable offences (crimes tried before a jury) in order to enable better analysis. In 1834, a decision was made to go further and include information on the personal characteristics of criminals – namely their sex, age and literacy – in the Criminal Returns.

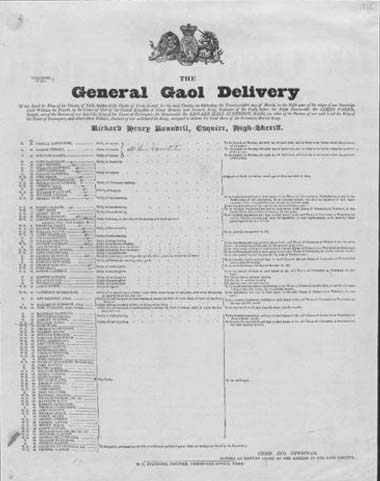

On 31 October 1834, a Home Office circular was sent to all the governors of prisons in England and Wales asking them to place, in their Criminal Calendars (lists of prisoners about to go to trial), against the name of each individual prisoner:

- a ‘W.R.’ for those who could read and write

- an ‘R’ for those who could read only

- an ‘N’ for those with neither skill

Not every keeper complied with the request, but many did, possibly because such information was already available in a large number of prison registers. The result of the initiative – national statistics on prisoner literacy – first appeared in the Criminal Returns for 1835 (published in 1836).

Activity 2 Literacy in the Criminal Returns for 1835

Below is a summary table created from the information in the Criminal Returns for 1835 (Table 1).

It gives the proportion of male and female prisoners committed for trial who could read and write, who could read only, who could neither read nor write, and for whom literacy could not be ascertained. Look at the table now, and consider the following questions:

- ‘Literacy comprises two skills: the ability to read and the ability to write.’ With this in mind, how literate were prisoners tried for indictable offences in 1835?

- What differences can you see between male and female prisoners?

- Can you see any problems with the categories being used here?

| Table 1 Literacy of persons committed for trial or bailed, 1835 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Read and write | % Read only | % Neither read nor write | % Literacy not ascertained | |

| Males | 46 | 18 | 33 | 3 |

| Females | 26 | 34 | 38 | 2 |

Discussion

- Strictly speaking, most prisoners sent for trial in 1835 were illiterate. Only 46% of males and 26% of females could read and write. However, it is still significant that well over half of the prisoners could at least read. The ability to read is in itself an important skill. Remember that large numbers of children (and adults) left formal education before they learned to write. That only 33% of male prisoners and 38% of female prisoners could neither read nor write could be regarded as an achievement in the absence of a system of universal, compulsory and free elementary education.

- The spread of the skills among male and female prisoners was uneven. A larger proportion of male prisoners could read and write, while a larger proportion of female prisoners could read only. This matches what we know about education outside the prison: in the early 1800s, girls were more likely to leave school early or to be taught at home, which meant that they were less likely to learn to write.

- The main problem with the categories used here was that they measured the presence of a skill, but not the degree of ability. Included among those who could read and write, for example, were men and women who could just about write their names, who could copy a passage from the Bible, who could write a letter home, and who could compose a critical essay. Similarly, among those who could read were men and women who could barely read words of one syllable, who could read a passage from the Bible but had no idea of its meaning, and who could read Shakespeare with ease.

Officials were aware of problems with the categories. In December 1835, new instructions were sent to governors of prisons in England and Wales, asking them to use the following scheme which graded prisoner literacy:

- ‘N’ for those who could neither read nor write

- ‘Imp’ for those who could read, or read and write imperfectly

- ‘Well’ for those who could read and write well

- ‘Sup’ for those who had a superior education.

Meanwhile, in 1836, a new statistical series was created – the Digest of Prisons – which included data on the literacy of all those committed to local prisons either to await trial or to serve sentences of imprisonment. For the Digest, literacy was also graded (i.e. N, Imp, Well, Sup).

The need to grade literacy increased the testing of prisoners and introduced a degree of subjectivity, or ‘observer bias’, into the data. This did not detract from the value of the statistics which were primarily being used to measure the literacy of the unskilled working class, from which many prisoners came, and for which there was, for much of the 1800s, no alternative system of measurement.