1 What is the global football business?

Football, like many other businesses, is often described as having a global reach or being global – but what do we mean when we say this? How does this relate to ideas of globalisation more generally?

Below is a short extract adapted from an article by two Scandinavian professors: Harald Dolles and Sten Soderman (2005). They explored some of the ideas of globalisation as they related to European football and the World Cup. As you read this piece think about the various different ways in which the football business might be considered to be ‘global’. You’ll use these ideas in Activity 1 that follows.

Globalisation: European football and its business challenges

European football is a huge and fast growing business operating worldwide and it is of increasing importance to ongoing research in international business and business administration.

The game is famous because it is linked to tradition and culture. It formed part of many of our childhoods, and its professional teams are on top of pyramid-like organisations of several leagues, with amateur players at all levels, from silver-aged veterans’ teams to kids’ teams. Football today is also an international business, as players are transferred frequently around the globe, international professional leagues thrive, and the European Cup finals or the FIFA World Cup finals are top media events (Beech and Chadwick, 2004).

The world of football has been referred to more and more as an industry in its own right. Arguably, its characteristics have been drawing closer to those of the service industry or the entertainment business. The ranking of football as a business activity has risen in the economies of those countries where football is promoted as the national sport. In many of these countries, it represents a significant percentage of a nation’s GDP, because football events also drive volume in a considerable number of other sectors, such as media, merchandising, advertising and brand promotion as well as in services like transport and catering. The globalisation of the football industry has provoked a concentration of resources in the hands of a few big European and South American clubs, which have had the ability and the economic resources to face down increased competition from emerging clubs and other businesses in the entertainment industry.

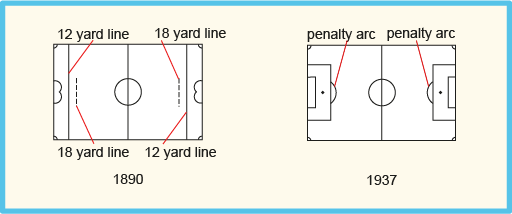

The game’s common worldwide rules (Figure 1) enable skilful players regardless of their ethnic and social background to play in teams which create enormous media interest. The problems and challenges in the field of football such as amateurism versus professionalism, young players going to big clubs, league teams versus national teams, branding and sponsorship growing as a source of revenue and the increasing reliance on the media for revenue, are the same everywhere on the globe.

In the US, football has successfully outmanoeuvred many other team sports, such as ice hockey, basketball or handball, and has been accepted as the number one sport as far as media attention and worldwide audience numbers are concerned. In 2009 the Champions League became the world's most watched sporting event eclipsing the NFL Super Bowl for the first time (Kuypers, 2014). According to the football international governing body, Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) statistics the FIFA World Cup 2010 was viewed by around 46% of the world’s population.

We can also consider the role of government in its relationship to sport including football. In this context, it is worth noting the philosophy of FIFA, and the environment for mega sports events created by governments worldwide. Staging mega sport events such as the World Cup is not merely an economic matter:

Football has always been one of the most convenient sports for serving political aims.

Through successful performance of national teams football provides a platform for displays of national capability and the instilling of national pride.

The 2002 World Cup was jointly hosted in Japan and South Korea with the governments of both countries having their own reasons for wanting the competition. The Koreans aimed at introducing the finals as a ‘catalyst for peace’ (Sugden and Tomlinson, 1998, p. 118) on the Korean peninsula, and the Japanese focused their bid on its ability to promote political stability, high technology and the country’s infrastructure (Sugden and Tomlinson, 2002). With its decision to award the tournament for the first time in history to Asian hosts and to more than a single nation, the FIFA moved strategically towards the globalization of football. In the bid to host the 2006 FIFA World Cup South Africa failed, losing to Germany by only a single vote in the final round. The BBC argued that a vote for South Africa was seen as a vote for Africa – which at the time had never hosted a World Cup tournament before, despite exporting some of the world's finest soccer players to Europe and other parts of the world – as well as a vote for developing countries. Later that decade history was made when Africa and South Africa were chosen to stage the 2010 FIFA World Cup.

It should be obvious by now that football is a global business, rapidly expanding and developing on a worldwide scale.