2.5 How impact craters form

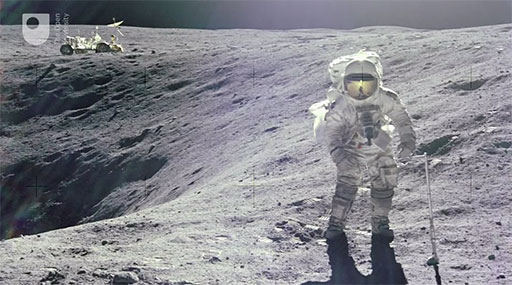

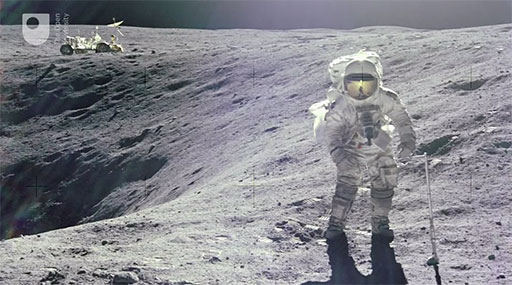

In this video Bevan French recalls crater studies in the 1960s and 1970s, and describes some of the processes that we now understand to occur when an impact crater is made.

Download this video clip.Video player: moons_1_vid021.mp4

Transcript

BEVAN FRENCH

I wanted to collect minerals from about the time I was eight years old, so naturally, I went into geology and went through degrees. I came out of graduate school in 1964 just as the Apollo programme was heating up and went from graduate school to the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Because we couldn’t get to the Moon and get rocks, most of the debate was on measuring craters at long distances and deciding whether they looked volcanic or they looked impact. So there wasn’t much known about the natural craters either on the Moon or on the Earth. The Apollo programme provided good evidence that craters on the Moon were the results of impact. And I think everybody finally conceded that. And that made meteorite impact a very important process.

When this meteorite hits and just dumps all its energy into a very small volume of a local environment, it produces intense shockwaves. Think of a sonic boom, but something on a scale of a thousand times larger. And these shockwaves go into the target rock, and then they produce deformations. Another thing that happens about impact craters is that they produce a lot of very unusual high-temperature melt. When you get very intense shocks, you actually leave so much heat behind in the rock that, when the shockwave has gone off, the rocks are heated to a couple of thousand degrees. And they melt, and these melting effects were much more common in the lunar samples. So if you look at a lunar crater, you’ll have a bowl. And inside it, there’ll be a deposit of rubble, which is a lot of busted up rock and melt and stuff that’s fallen in from the sides. And that would be what’s called the ‘crater fill.’ If the crater’s bigger, energy is so intense and the rock is so relatively weak that the centre of the crater actually rises up. The whole geological mainstream and the development of technology for dating rocks and doing geophysical works, all of this is relevant to the problem of impacts. And we have discovered some just fantastic things about how important it is, what big structures it can make, and what the global effects can be. It has been literally an explosion of knowledge. We’ve suddenly realised, in the case of the Earth, that impact is much more important than we ever thought it was.

Interactive feature not available in single page view (see it in standard view).