1 Early theories about water on the Moon

When astronauts first visited the Moon in 1969, there were very few certainties about the presence of water, but no lack of hypotheses. When Apollo 11 landed and samples of the Moon’s surface were first collected, the initial analysis did not detect any water and indeed as you saw in Week 5, the samples appeared almost completely unaltered with little to no water interaction evident.

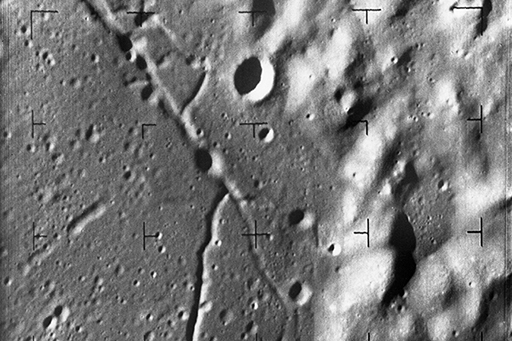

The idea that water has been present on the Moon has been debated for centuries. This includes many strange theories such as one proposed by Danish astronomer Peter Andreas Hansen in 1856. Hansen believed that the Moon’s centre of mass (its gravitational centre) is offset from its geographical centre, which could allow a large atmosphere to exist on the far side of the Moon, under which oceans and rivers could exist. The prevailing opinion by the time astronauts visited, however, was that the very low atmospheric pressure would not allow liquid water to exist anywhere on the surface. In the mid-20th century, the idea of water existing on the surface was taken up by Nobel Prize winner Harold Urey. Based on the Ranger 9 images, there appeared to be channels created by flowing liquid. Urey was eventually proven wrong by the Apollo 15 mission when one of the channels, Hadley Rille, was visited by astronauts Dave Scott and Jim Irwin and it was evident that the channel was created by lava, not water. However, Urey’s arguments were a key driver for NASA to explore the Moon and they helped greatly in the space programme. As you’ll see in this week, although Urey was mistaken about Hadley Rille, he wasn’t completely wrong.

The lack of water on the Moon was further corroborated when it was established that the regolith returned from the Moon resulted from lava break-up by billions of year of meteorite impacts rather than from water-related processes. At the time no water could be detected inside any minerals in the samples brought back by the Apollo missions; in particular, there was a lack of the most common hydrated mineral found in basaltic rocks on Earth, amphibole.