3.2 Miranda

Miranda is the fifth-largest moon of Uranus. It was discovered in 1948 by Gerard Kuiper and was the last moon of Uranus to be discovered before Voyager 2 flew by in 1986. At the time of the flyby, the south pole of Uranus, which has an extreme axial tilt, was pointed towards the Sun. Its moons’ orbits are all in the plane of its equator, so their south poles were pointed sunwards too. Consequently, their northern hemispheres were in darkness and could not be seen. We have nice images of the illuminated southern hemisphere of Miranda, but its other side remains a mystery.

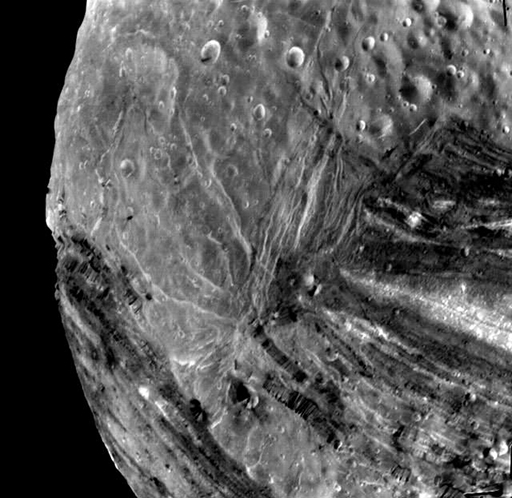

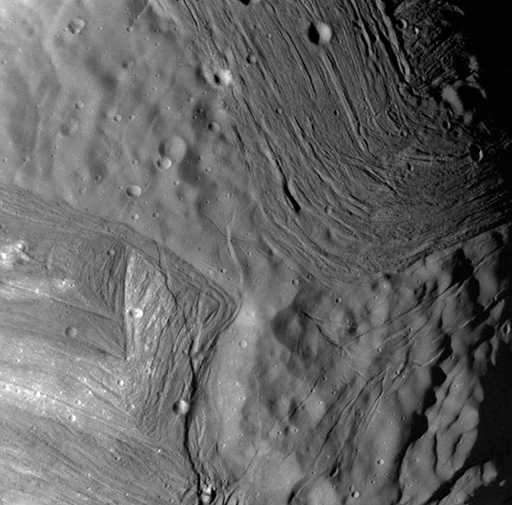

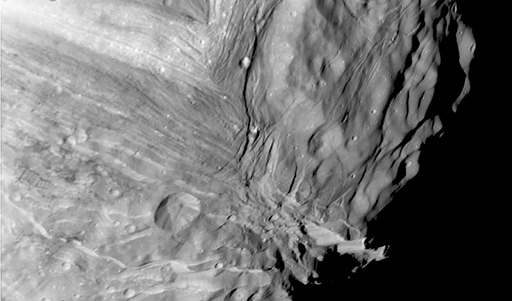

The surface of Miranda is very interesting geologically, with features observed that are unique among known objects in the Solar System. These features are known as coronae (the plural of ‘corona’); defined as ridges and valleys peppered with fewer craters than the surrounding terrain. These are separated from the more heavily cratered regions by sharp boundaries. These features give Miranda a very interesting appearance, looking like a jigsaw puzzle that was put together from mismatched pieces. One early explanation for this (now discredited) is that the moon was shattered by a large impact and then reassembled from the pieces. Other possibilities are that the coronae result from meteorite impacts that caused the icy surface to melt, followed by slush rising to the surface and refreezing or that the coronae are above sites where tidal heating was concentrated in the distant past, which would mean that the coronae have some kind of cryovolcanic explanation.

If tidal heating was responsible for the coronae, it could have resulted from a past episode of orbital resonance with one of Uranus’ other satellites, probably Umbriel or Ariel.

Like other moons of Uranus, Miranda is thought to consist of roughly equal amounts of water-ice and silicate rock.