3.3 Ariel

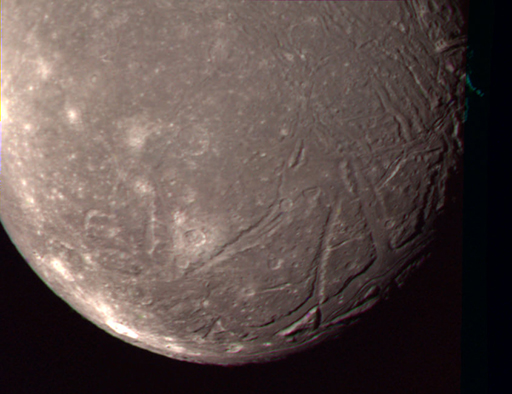

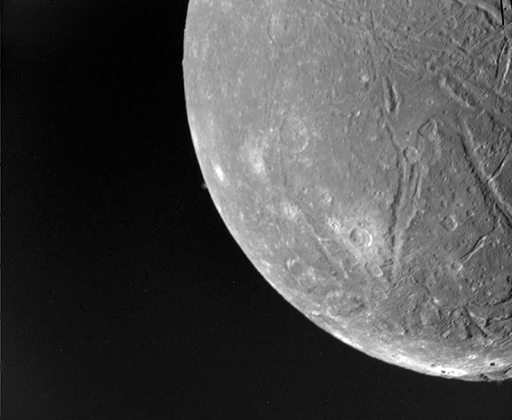

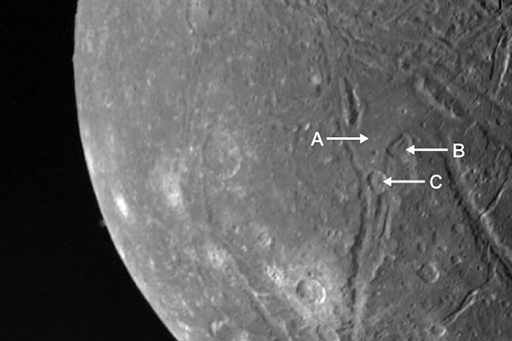

The terrain on the right is remarkable for the number of straight-sided, presumably fault-bounded, troughs. The more fully sunlit region in the upper left has fewer troughs.

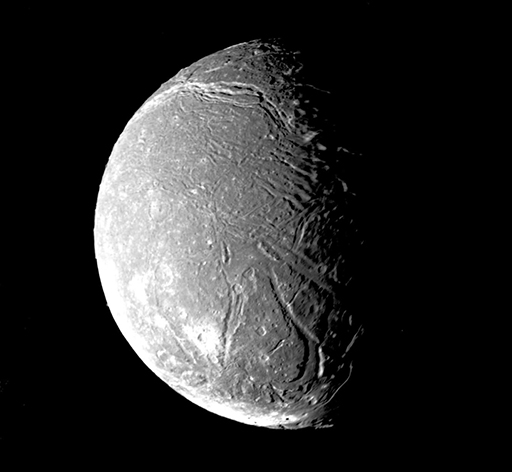

Ariel is the fourth-largest moon of Uranus. It was first observed in 1851 by William Lassell and was seen in close-up in 1986 by Voyager 2. It is thought to be composed of a rocky core and icy mantle. Like Miranda, it is thought to be made up of roughly equal proportions of water-ice and rock, with the rock possibly including some material that is carbonaceous in nature. Carbon-dioxide-ice has also been detected on Ariel and there may be ammonia-ice too.

Multiple geological features have been observed on the surface including craters, ridges and plains. The south pole is characterised by extensively cratered terrain; this is thought to be the oldest region, as the density of craters indicates a lack of resurfacing. The cratered terrain is bordered by regions of terrain cut by steep-sided troughs. These can be hundreds of kilometres in length and up to 20 km in depth – that’s nearly 12 times the depth of the Grand Canyon. The troughs are thought to be caused by parallel geological faults causing the floor to drop down. Evidence that Ariel has the most recent geological activity of all the moons of Uranus is provided by the smooth, relatively crater-free material covering the floors of some of these troughs and spilling out beyond their ends. This is thought to represent cryovolcanic flooding, with ‘lava’ formed from a mixture of ammonia-ice and water, erupted from below as a result of tidal heating. Lava made of an ammonia–water mix would be liquid even at −100 °C and is not too hard to imagine on the surface of a moon whose normal surface temperature is about −200 °C.