3.2 Forming other moons

But what about other moons?

Giant impacts can’t be used to explain the numerous moons of the giant planets, or the two tiny moons of Mars. The moons of Mars, namely Phobos and Deimos, are believed to be asteroids that were captured into orbit around Mars. They have an irregular non-spherical shape and a composition similar to that of other asteroids. The same explanation applies for the small, irregular outer moons of the giant planets, many of which have orbits that are very inclined or in some cases, retrograde. But what about the large moons of the giant planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune?

Most larger moons orbit very close to the planet’s orbital plane and in the same direction as the planet spins (remember prograde orbits). This demonstrates that the moons share spin with their planet and this is a clue that they have a common origin.

These larger moons were probably formed in orbit around their planet from material in the proto-planetary disc that wasn’t formed into the planet itself. The temperature in the centre of the disc around the Sun would have been very high near the Sun but decreasing as you move out towards the edge of the disc. There would have been a similar but less extreme temperature gradient working outward in the smaller disc surrounding each giant planet, and this could be responsible for the decrease in density with distance from the planet observed in the Galilean moons of Jupiter (the four of Jupiter’s moons discovered by Galileo).

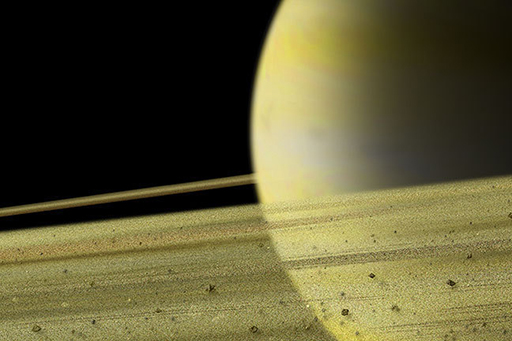

The small ‘inner moonlets’ of the giant planets, and their rings, are probably remains of bigger satellites that were broken up by collisions or ripped apart by tidal forces.

If you wanted to look into this further, you might find the following link of interest: A moonlet lurking in Saturn's A Ring? An update on plans to get a spatially-resolved image of what may be a moonlet (nicknamed "Peggy") embedded in the outer edge of the densest part of Saturn's rings.