1.1 Past volcanism on the Moon

A geologically active surface can mean many things, but for many planetary geologists it means volcanoes. For volcanoes to form, an eruptible magma is required. This means an internal melting mechanism such as heating is necessary for the production of the magma below ground, which can then rise towards the surface. The addition of gas aids the rise of magma and helps to make eruptions explosive, explaining the difference between a jet of magma shooting skywards and a gentle flow of lava onto the surface.

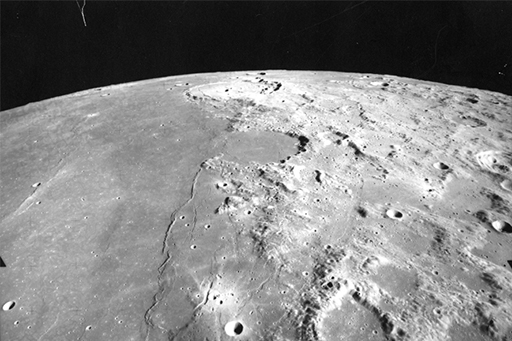

Evidence of volcanic flows on the Moon can be seen as smooth plains overlying older, more cratered surfaces. However, our Moon has not been majorly active for a long time. Most lunar maria were flooded by lava about 3 billion years ago, and the most recent volcanic activity on the Moon seems to have been more than a billion years ago. Since then, the Moon has gradually frozen solid and is no longer capable of producing magma, as the radioactivity keeping the deep mantle and core hot has diminished. How then, is it possible that volcanism on other moons still occurs? Io is the most volcanically active body in the Solar System, yet it is only marginally larger than our own Moon.