3.1 Rhea

Rhea (diameter 1527 km) is the second-largest moon of Saturn. It was first discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1672 and was imaged by Voyager 1 in November 1980, by Voyager 2 in August 1981 and on various occasions by the Cassini spacecraft during its orbital tour of Saturn’s family of moons that began in 2004.

Before the launch of the Voyager space probes, most scientists expected all moons to be heavily cratered due to multiple impacts, with no mechanism of resurfacing, such as cryovolcanism, to erase the craters. Although many of the moons proved them wrong, Rhea is a good example of what was originally expected. Rhea lacks signs of cryovolcanism and its most notable geological features are its many craters. It has more craters per square kilometre than either Dione or Tethys (two other heavily cratered moons of Saturn). It is not known why this is the case, but it could be that the other moons’ closer proximity to Saturn allowed stronger tidal heating in the distant past and this gave rise to greater internal heating, allowing liquid water to reach the surface and refreeze, effectively erasing craters. However, it could also be that Rhea simply received a heavier bombardment than either Dione or Tethys.

Apart from its craters, the Voyager probes revealed wispy lines that cut across both craters and plains. The Cassini orbiter’s more detailed images showed that the wispy lines are canyons, suggesting that even Rhea may have had tectonic activity in the past. Surface features like these are also present on Dione and Tethys.

Rhea has a density of 1.233 × 103 kg m−3 suggesting that it is composed of around three-quarters water-ice and one-quarter rock. Measurements by Cassini suggested that Rhea is composed of a homogenous mixture of ice and rock, and it has been likened to a dirty snowball.

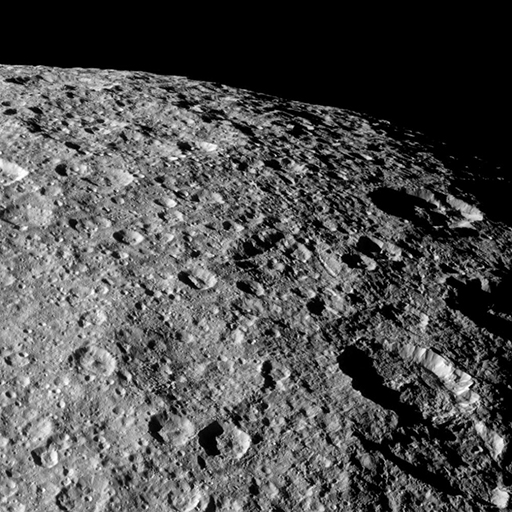

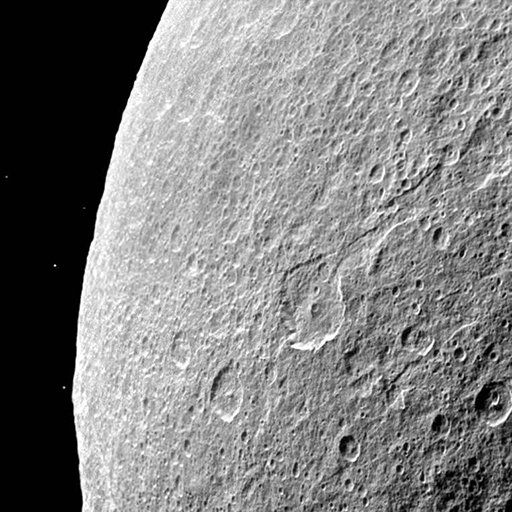

The area in view is several hundred kilometres across.

This surface is scarred by craters of a wide range of sizes. Some of the older craters are hard to see, because they have been partly overprinted by younger craters or covered by material thrown out of adjacent craters during impact.

Although dominated by craters, there has been some fracturing or faulting of the surface: look to the right of the large (70 km diameter) crater near the centre. This was actually the night side of Rhea and it is a long-exposure image made by the light reflected onto Rhea by Saturn. Two stars are visible to the left of the disc.

See also: Google maps of moons [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . Visit this link for an introduction to the Google maps of moons, and click the appropriate link in the blog play with them!