Stained glass windows by Harry Clarke. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Stained glass windows by Harry Clarke. Source: Wikimedia Commons

When you think of the Gothic you might think of vampires, ruined castles, graveyards, spectres and haunted heroines. You probably do not automatically think of Ireland, but in fact, the Gothic—a cultural form that includes novels, films, art and even computer games—owes a great deal to Irish writers for more than 250 years ago. This course will help you discover why Ireland was the perfect melting pot to establish a horror genre which has taken over the world.

While Irish literature is often associated with the Nobel Prize-winning poetry of Seamus Heaney or the famously difficult modernist prose of James Joyce, the Gothic tradition gives us a whole new lens through which to read the legacy of literature in Ireland. The Irish Gothic tradition is diverse, spanning time, space and literary genre. From around 1760 there is evidence of Irish writers beginning to engage with Gothic tropes and themes. While the work of Thomas Leland, Elizabeth Griffiths and Regina Maria Roche are often considered some of the earliest examples from this tradition A. M. Shine’s The Watchers (2022) and Jan Carson’s haunted whodunnit The Raptures (2022) are evidence that the tradition is still very much alive and well in Ireland. Many of Ireland’s most famous Gothic writers over the past 250 years were born in or associated with the island’s largest city, Dublin, including Charles Maturin (1782-1824), Bram Stoker (1847-1912), Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) and Elizabeth Bowen (1899-1973), but the map of Gothic literary production in Ireland goes well beyond Dublin: Roche (1764-1845) was born in Waterford and ghost-story writer Charlotte Riddell in Carrickfergus (1832 – 1906), while Shine was born in Galway and Carson in Ballymena.

In this resource, you will explore examples of the Irish Gothic from the eighteenth century to the present day and examine the influences that shaped them. Along the way you will get the opportunity to see how Irish writers have created ghostly effects in their work and even get a chance to have a go yourself at creating creepy characters and sinister settings.

An introduction to early Irish Gothic

In this article you will explore the emergence and development of an early Gothic tradition on the island of Ireland, examining the unique social and historical factors that influenced the development of gothic and ghost-story writing over the course of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. An extract from Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872) will give you a chance to see features of the Gothic at work within a literary example from the period. You can then try out some of these devices for yourself through a creative writing exercise.

Let’s begin by setting out the basic characteristics of what is meant by ‘the Gothic’ in literature.

What is Gothic?

What do you think of when you think of the “Gothic”? You might think of ghosts and the supernatural, or you might even think of literary examples like Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), a famous nineteenth-century tale about vampires which has inspired countless generations of writers and film makers.

Lupita Tovar and Carlos Villarías in Dracula (1931). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Lupita Tovar and Carlos Villarías in Dracula (1931). Source: Wikimedia Commons

One feature of the Gothic that is immediately recognizable is its setting. The name “Gothic” is derived from medieval Gothic architecture, so it is not surprising that ruined abbeys, moonlit castles and abandoned churches abound early Gothic novels and art. The word was first introduced by Horace Walpole in his 1764 novel, The Castle of Otranto, which he subtitled "A Gothic Story", which whisks readers away to a medieval Italian castle. However, it should be noted that the earliest recognized Irish Gothic novels predate Walpole’s novel.

Ruined buildings in Gothic fiction and art create the genre’s characteristic atmosphere of danger, fear, threat and decline, and reflect the genre’s preoccupation with once-thriving worlds beset by decline and decay.

Common Gothic themes include revenge, murder, dark sexuality and the supernatural. The genre’s narrative style can often be complex, incorporating shifting narrators, time frames and locations. You will also find many common plot devices in Gothic fiction, from discovered letters or diaries and malevolent family curses to live burials and unexplained maladies, both physical and psychological. A recognizable cast of character emerge within the Gothic tradition. Supernatural beings such as vampires, ghosts and demons often appear alongside men and women who typify extremes of good and evil: monks and nuns, violent tyrants and naïve damsels in distress, Byronic heroes and femmes fatales.

It might be worth noting that although such characterization appears to reinforce gender stereotypes, the genre provided remarkable scope for exploring women's social roles and sexual desires. Writers like Ann Radcliffe (with her hugely successful novel The Mysteries of Udolpho, 1794), Mary Shelley (the author of the influential Frankenstein, 1818) and Charlotte Brontë (the enduringly popular Jane Eyre, 1847) used Gothic narratives and tropes of the persecuted heroine to challenge notions of patriarchal control and address themes such as sexual violence. Some Gothic works also featured more assertive heroines, offering a counterpoint to the traditional passive female lead: Sheridan Le Fanu’s female vampire-driven romance Carmilla (1872), which we will explore below, is one good example.

Hopefully you are beginning to develop a sense of some key features identified with the Gothic tradition, which influenced not only writers but also visual and fine artists. Below is a short activity to test your understanding of key Gothic themes and elements, focused on an illustration by the Irish artist Henry (Harry) Clarke.

Identifying the Gothic - Henry Clarke

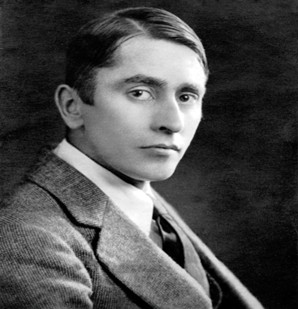

A photograph of Henry Clarke. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A photograph of Henry Clarke. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Harry Clarke (1889 – 1931) was a Dublin born artist who specialized in striking stain glass windows and book illustrations. He produced over sixty stain glass commissions, which frequently exhibit his interest in the fantastic and macabre. His work was characterised by technical innovation, a brilliant use of jewel-like colours and a unique and unsettling style of drawing of figures. He produced much work for churches—see, for example the Honan Chapel in Cork University.

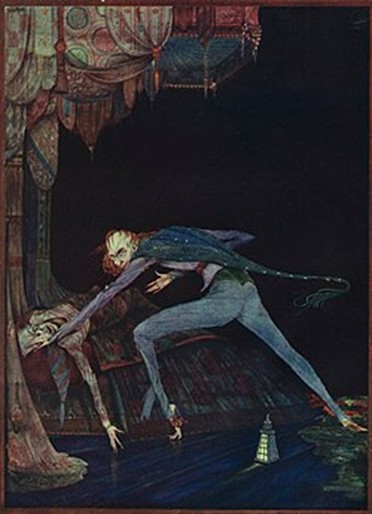

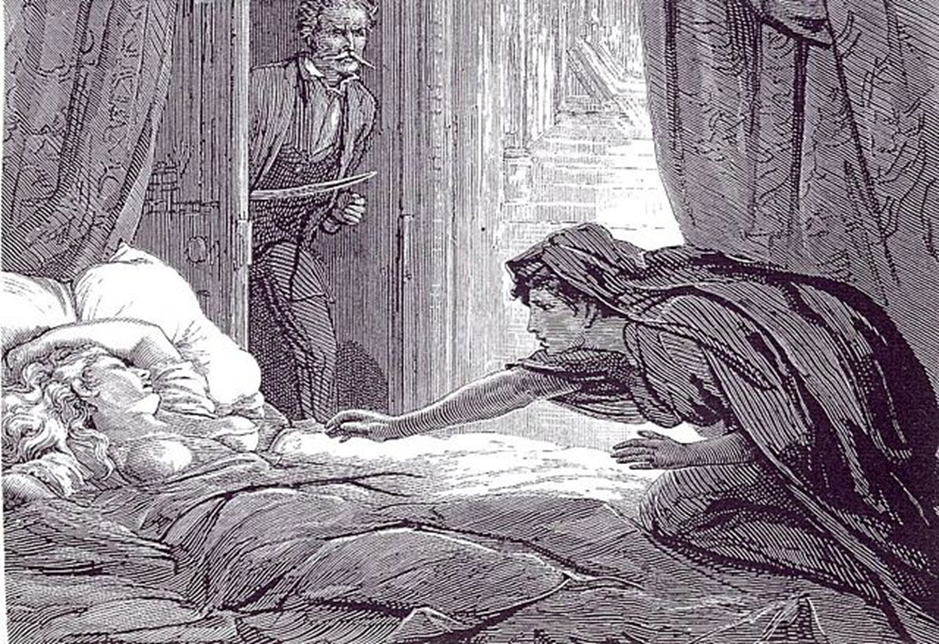

The image below is taken from a series of colour-plates Clarke designed for George G. Harrap & Co to accompany a version of Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination, originally published by Poe in 1839. This illustrated edition, published in 1923, secured Clarke’s place as a respected artist with links to the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements. The image below was designed as an illustration for one of Poe’s best-known tales,‘A Telltale Heart’.

Harry Clarke's illustration to "A Telltale Heart". Source: Wikimedia Commons

Harry Clarke's illustration to "A Telltale Heart". Source: Wikimedia Commons

Task 1

Look at the image carefully. What characteristics of the Gothic can you identify? (You do not need to be familiar with Poe’s story ‘A Telltale Heart’)

Reveal answers

You may have identified any number of features associated with the Gothic. Here are just a few:

- Its inexplicable and strangely disturbing atmosphere

- The threatening and monstrous looking figure leaning over the bed

- The dark atmosphere and background

- The vulnerability of the figure on the bed and a sense of danger they are in

- A sexuality or eroticism, though it is unclear and shadowed

- A sense of irrationality, the opposite of a waking rational moment.

One further characteristic of the Gothic: the Uncanny

‘The uncanny’ is a key term associated with the study of Gothic fiction today, referring to the strange, eerie feeling conjured up by an encounter with something that is simultaneously both familiar and strange. Although the term was not officially coined until the early twentieth century by German psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch in his essay On the Psychology of the Uncanny (1906), there is evidence that Gothic writers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were familiar with this phenomenon and explored it extensively in their fiction. German fantasy and horror-writer E.T.A. Hoffman featured a mechanical doll with frighteningly lifelike qualities in his story The Sandman (1816) for example, while the grotesque humanity of Frankenstein’s monster, sewn together from human and animal body parts, horrified and fascinated the readers of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). Similarly folktales and ghost-stories featuring revenants and the undead relied on the effect of the uncanny, playing on the concept of beings who are dead coming back to life in an altered form.

Another facet of the uncanny in eighteenth and early nineteenth fiction occurs when characters are presented with versions of themselves, whether it is through the appearance of twins, mirror images, shadows, corpses, or even portraits. Uncertainty about whether an object is alive or not is a hallmark of the uncanny and is a common feature of Gothic narratives and art.

A good example of the uncanny in early Gothic storytelling is the figure of the “doppelganger”, a character from late eighteenth-century German folklore. Drawn from the German words ‘doppel’ (double) and ‘gänger’ (walker), the doppelganger was a spiritual shadow self or double of a living person, the sight of whom was not only terrifying in its own right, but often a harbinger of bad luck or death.

Now that you have a good grasp of the Gothic and some of its defining characteristics, let’s focus in on the Irish tradition more specifically, examining the ways in which Irish writers from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries engaged with the Gothic in their work.

The Early Irish Gothic Tradition

Lluís Rigalt - Night Landscape with Gothic Ruins. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Lluís Rigalt - Night Landscape with Gothic Ruins. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Irish writers were quick to take advantage of the appeal of Gothic forms and ideas when they first emerged in the late eighteenth century. Indeed, their work often rivalled that of English writers in popularity in the 1790s. Literary historian Christina Morin has made a case for the importance of first-wave Gothic writers such as Regina Maria Roche, Thomas Leland and Elizabeth Griffith, who used Gothic fiction as a vehicle for drawing attention to specifically Irish themes and concerns. The nineteenth century saw a fuller flowering of distinctive Irish Gothic writing and in fact, some of the most famous examples of nineteenth-century Gothic writing can be traced to Ireland. It has been said that Irish Gothic writing tended to be dominated by Protestant male writers such as Charles Maturin (Melmoth the Wanderer 1820), Sheridan Le Fanu (Carmilla 1872 and Uncle Silas 1864), Oscar Wilde (The Portrait of Dorian Gray 1890) and Bram Stoker (Dracula 1897). What was it about the Gothic that attracted these writers to the Gothic form? How did the contemporary historical context, including social crises such as the Great Hunger, contribute to development of Gothic fiction in Ireland?

Influences on the Irish Gothic in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

Photograph of a gothic window in a ruined abbey wall. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of a gothic window in a ruined abbey wall. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Political and Religious Instability: A Nation Divided

Eighteenth-century Ireland was an island and a society deeply divided along religious and class lines. The majority of the Irish population was Catholic, particularly in the south and west of the island with significant pockets in the north, while Ulster was largely Protestant. These divisions were in many ways the result of English plantation policies of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries which resulted in Irish-owned lands being confiscated and colonized by British settlers, with a Catholic ruling-class largely displaced by an Anglo-Irish one. The Georgian period saw the flowering of an Anglo-Irish Protestant Ascendancy, who enjoyed unchallenged political and social superiority. This system was maintained by laws which strongly restrained Catholics from owning property, entering professions and fully engaging in political life, creating a society with extreme religious and political tensions. The elegant ornaments of this regime were a proudly Irish, if exclusively Protestant, parliament, an elegant Georgian cityscape in Dublin and a countryside filled with large Anglo-Irish country estates boasting neoclassical ‘Big Houses’.

But change was in the air as the eighteenth century gave way to the nineteenth. Irish radicalism in the 1790s posed a significant threat to the Protestant Ascendency who, though they identified themselves as nationally Irish, still felt themselves to be deemed too English by their Catholic countrymen. The Irish Act of Union in 1800, which merged the Kingdoms of Ireland and Great Britain, was intended to safeguard Anglo-Irish interests but ultimately lead to their significant loss of status, wealth and security with the closure of an independent Irish parliament. Isolated in their grand stately homes and surrounded by oppressed and resentful Catholic tenant farmers, the Anglo-Irish Protestant community found itself a minority whose control and dominant position in Ireland was slipping away.

It is no coincidence that the Irish Gothic novel emerged and flourished during this period of social and political instability. Anxiety over the loss of Anglo-Irish political legitimacy and prestige has been seen as a factor fueling the writing of Gothic fiction in this period. The horror and paranoia of the Gothic tale was a way of exploring and externalizing the fears and anxieties of an entire social class in Ireland. This is particularly clear in the way that early Irish Gothic fiction often presents Catholic characters and traditions as strange and even diabolically Other: the depiction of wicked monks and malevolent religious superstition reinforced a narrative of fear and decline that suited Anglo-Irish interests in this period. In this way, Anglo-Irish writers can be understood as having turned to the Gothic for images and narratives which would enable them to find new ways of articulating a stable identity in the midst of tremendous change.

Famine and disease: A Nation Under Threat

While the Act of Union introduced massive political changes and instability to Ireland in the nineteenth century, nothing could have prepared it for the dramatic demographic changes introduced by famine and disease in the 1830s and 1840s. Cholera epidemics, notably in Sligo in 1832, led to the death of thousands of victims, whose skin took on a deathly colour of blue. Fear of contagion was rife. Stories circulated of people turning on neighbours suspected of carrying the disease, as well as victims being buried alive or walled up in their own dwelling to perish. As a child, Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula (1897), heard accounts of cholera from his mother who had survived the Sligo epidemic.

Worse was to come. the Irish famine of 1845-52 or The Great Hunger’ was a cataclysm in Irish history, leading to the death of over one million people and the emigration of up to 20% of the population. Stories spread of dark events - the dead unburied, cannibalism, and even corpses with mouths covered in green foam from attempts of the starving to eat grass. The reality was no less horrible--bodies were frequently buried in unmarked mass graves, while skeletal figures walked the roads, near death from starvation, seeking what sustenance they might find. It can be no surprise that starvation and disease left the public preoccupied with death and the afterlife.

Irish Famine Monument. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Irish Famine Monument. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Even in times of plenty and free of disease, the macabre was never far away in nineteenth century Ireland. The design of Glasnevin cemetery, built in Dublin in the 1830s, featured high walls and watchtowers so that armed guards might deter and detect the practice of body-snatching. Sometimes referred to as ‘Resurrectionists’ or ‘Sack’em Up Men’, these criminals unearthed fresh corpses to sell to the medical schools to dissect. .Living in a time of horrific loss and macabre practices clearly influenced the Irish Gothic writers of the day in terms of the content and themes they explored. It can be no surprise that starvation and disease left the public preoccupied with death and the afterlife.

New Forms of Literary Nationalism: Irish myth and folklore

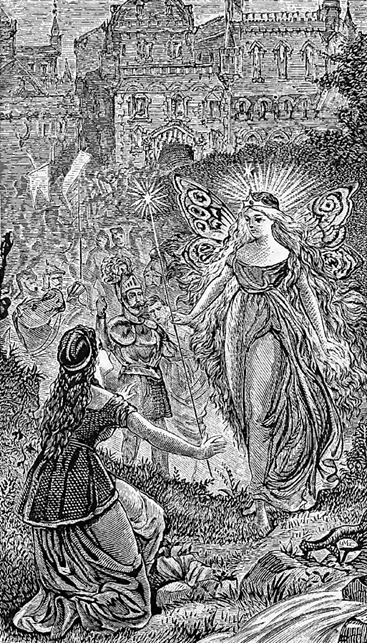

There was a growing fashion for collecting and publishing folk and fairy-tales at the beginning of the nineteenth century. These volumes, strongly associated with the expression of national character—the spirit of the ‘volk’ or people—were wildly popular with readers: the Brothers Grimm’s Kinder- und Hausmärchen [Children’s and Household Tales] became a bestseller when it was translated into English in 1823. In many ways, the folktale can be classed as the original Gothic story. Folktales regularly introduce elements of the supernatural, with a central character in need of rescuing. They were in many ways a rich storehouse for Gothic fiction, lending their characters, narrative structures and supernatural elements to this developing genre.

Published in 1825, Thomas Crofton Croker’s popular Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland was the first of a flurry of publications which aimed to capture Irish oral story-telling traditions. The intermingling of local customs with Irish mythology and fairy folklore, in these volumes, which were originally published in England, powerfully influenced the perception of Irish national character to readers in Ireland and elsewhere. But for Irish Gothic writers, folklore was a particularly rich source of inspiration. As literary critic Elizabeth MacAndrew notes, Gothic writing takes ‘the stuff of myth, folklore, fairy tale and romance’ and uses it to give form to the ‘amorphous fears and impulses’ of individuals and societies (pp 3-4). This was certainly the case for Irish writers who found in Gothic writing a vehicle for expressing both national identity and the uncertainties and terrors of their contemporary political reality.

Eileen and the Fairy Queen. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Eileen and the Fairy Queen. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fair, Brown, and Trembling

Here is an example of an Irish folktale story that that will feel very familiar to you: Fair, Brown, and Trembling. It is a variation of the Cinderella story, collected by Jeremiah Curtin in Myths and Folk-lore of Ireland (1890) and Joseph Jacobs in his Celtic Fairy Tales (1892).

Cinderella, or, The little glass slipper (1908). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Cinderella, or, The little glass slipper (1908). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Basic Plot

Fair, Brown and Trembling were the three daughters of King Hugh Cùrucha. At the start of the story, jealous of their youngest and prettiest sibling, Fair and Brown hide her away, out of view of any potential husbands.

Fair becomes engaged to a prince, and then one day Trembling encounters a wise henwife, who tells her to visit the local church three times. She follows this advice, and at the church she meets the prince herself. Seeing Trembling’s beauty for himself – he soon forgets Fair and marries her younger sister. I probably do not need to mention he identified her by her lost glass slipper, for you to recognize the similarities between this tale and Cinderella! (Perrault 1697)

Along the way the happy couple face further catastrophe when Fair lets Trembling be swallowed by a whale, but she is soon set free and as in all good folktales, Fair gets her comeuppance. In this case, being set adrift on the sea in a barrel.

We can clearly identify Gothic elements of the innocent beauty who requires saving, the murderously wicked villain, and the intervention of the wise and otherworldly henwife.

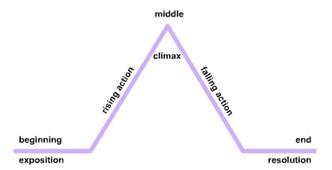

One of the keys to creating a successful short story is simplicity, and folktales employ this in a way that makes the narrative memorable and easy to repeat. They usually employ a three-stage story arc: an inciting incident (Trembling meeting the henwife), a dramatic climax (Trembling being swallowed by the whale) and a satisfying conclusion or return to normality (Fair being punished and Trembling and the Prince getting their happy ever after.)

The Plot mountain. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Plot mountain. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Task 2

Can you think of another example of a folktale or Gothic story that would fit this story arc?

Reveal answers

You have probably thought of several examples of this traditional plot arc, which is used for everything from TV soaps to novels. Here is an example of a well-known Gothic short story that fits this simple structure: The Brother’s Grimm, Little Red Riding Hood. At the start of the story, our protagonist introduces us to her normal life living with her family. The inciting incident, or hook, occurs when her mother asks her to deliver a basket of food to her Granny, who lives in the forest. The slow rise in tension occurs as she makes her way through the woods and we become aware of the Big Bad Wolf. The Climax is the reveal of the wolf masquerading as her Granny in bed and (depending on the version you were brought up with) the arrival of the woodcutter to rescue the girl. We then have a fall in action as events return to normal and the resolution. There are other kinds of plot structure, but this simple three act construction is common in many genres, from film scripts, to radio plays, to novels. It works effectively with the Gothic, as something is at stake from very early on – hooking us in immediately.

Carmilla (1872) by Sheridan Le Fanu

Photograph of Sheridan Le Fanu. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of Sheridan Le Fanu. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Let’s take a closer look at a specific example of nineteenth-century Irish Gothic literature. Dublin-born Joseph Thomas Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873) is regarded as one of the pioneers of Gothic fiction. He published his first ghost story The Ghost and the Bone-Setter in 1838, and gained fame for his novels such as The House by the Churchyard (1863) and Uncle Silas (1864)

Illustration from Carmilla. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Illustration from Carmilla. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Dracula is arguably the most familiar example of the Irish Gothic vampire tale; however, Carmilla, published in 1872, preceded it by 25 years and already has in place all the classic elements of the vampire story - the lonely location, the monster’s power to fascinate and beguile the transformation to animal form, the feeding upon the young and lovely female, and the forming of a resolute band to track it to its crypt and destroy it in the most appropriate way: with a stake to the heart.

At this point you may want to track down a copy of Carmilla so that you can read the text in its entirety. You can also read a copy online at Project Gutenberg.

Here is a basic summary of the novel’s plot.

Carmilla: basic plot summary

The teenage protagonist, a girl called Laura, lives with her widowed father in a lonely castle in an Austrian forest. Laura has a dream, age six, in which a beautiful girl visits her bedroom and despite no mark being found, Laura claims she experiences a needle like pain in her breast.

When she is 18 her father tells her a family friend is coming to visit, bringing his niece as a companion for Laura, but this girl mysteriously dies before she arrives. Shortly after there is a carriage accident and another girl injured in the accident is taken in to recuperate at the castle. This is Carmilla. Both girls recognise each other from their shared childhood “dream". Carmilla refuses to provide any information about her background - though Laura notes she looks very like the woman in the portrait of a distant ancestor, a Countess Karnstein.

Illustration from Carmilla by Friston. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Illustration from Carmilla by Friston. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The girls become close friends. Carmilla is mysteriously nocturnal and anything religious causes her great pain. She makes romantic overtures towards Laura. Girls in the nearby town begin to die of a mysterious illness. Laura has a nightmare where a large black cat enters her bedroom and she feels two needle like pains in her breast. The cat then takes on the shape of girl and leaves, walking through a locked door. Laura becomes ill and a small mark reveals where she has been bitten. The family friend arrives and tells the story of the death of his niece - a similar story to Laura’s experience, too similar.

What makes Carmilla different from Dracula is the central sexual tension between two female characters, which has lead to Carmilla being signalled out as literature’s first lesbian vampire (See Elizabeth Signorotti, ‘Repossessing the Body’ 1996). Her relationship with the heroine Laura is a deeply felt emotional one for both girls. True to its Gothic story form we see Laura succumb to an otherworldly temptation that has terrible consequences for her. Feminist critics have understood the novel as expressing the constraint of Victorian women, unable to express their wants and desires. In this reading the vampire lesbian becomes an antitype to heterosexuality as experienced in Victorian wifedom.

Even on the basis of this plot summary, some readers might have recognized elements which distinctly suggest the uncanny. Let’s take a closer look at an extract from Le Fanu’s novel to see, through close reading, how he creates this unsettling effect in the text.

Task 3

Read the following passage from Carmilla, taking note of any elements you encounter that recall the discussion of the uncanny above. How does Le Fanu conjure up a sense of unease and even imminent danger in this passage?

Show extract

[At this point in the novel Laura meets Carmilla for the first time, when Carmilla is recovering in Laura’s home from her carriage accident]

[……] Our visitor lay in one of the handsomest rooms in the schloss. It was, perhaps, a little stately. There was a somber piece of tapestry opposite the foot of the bed, representing Cleopatra with the asps to her bosom; and other solemn classic scenes were displayed, a little faded, upon the other walls. But there was gold carving, and rich and varied color enough in the other decorations of the room, to more than redeem the gloom of the old tapestry.

There were candles at the bedside. She was sitting up; her slender pretty figure enveloped in the soft silk dressing gown, embroidered with flowers, and lined with thick quilted silk, which her mother had thrown over her feet as she lay upon the ground.

What was it that, as I reached the bedside and had just begun my little greeting, struck me dumb in a moment, and made me recoil a step or two from before her? I will tell you.

I saw the very face which had visited me in my childhood at night, which remained so fixed in my memory, and on which I had for so many years so often ruminated with horror, when no one suspected of what I was thinking. It was pretty, even beautiful; and when I first beheld it, wore the same melancholy expression. But this almost instantly lighted into a strange fixed smile of recognition. There was a silence of fully a minute, and then at length she spoke; I could not.

“How wonderful!” she exclaimed. “Twelve years ago, I saw your face in a dream, and it has haunted me ever since.”

“Wonderful indeed!” I repeated, overcoming with an effort the horror that had for a time suspended my utterances.

“Twelve years ago, in vision or reality, I certainly saw you. I could not forget your face. It has remained before my eyes ever since.”

Her smile had softened. Whatever I had fancied strange in it, was gone, and it and her dimpling cheeks were now delightfully pretty and intelligent.

I felt reassured, and continued more in the vein which hospitality indicated, to bid her welcome, and to tell her how much pleasure her accidental arrival had given us all, and especially what a happiness it was to me.

I took her hand as I spoke. I was a little shy, as lonely people are, but the situation made me eloquent, and even bold. She pressed my hand, she laid hers upon it, and her eyes glowed, as, looking hastily into mine, she smiled again, and blushed.

She answered my welcome very prettily. I sat down beside her, still wondering; and she said:

“I must tell you my vision about you; it is so very strange that you and I should have had, each of the other so vivid a dream, that each should have seen, I you and you me, looking as we do now, when of course we both were mere children. I was a child, about six years old, and I awoke from a confused and troubled dream, and found myself in a room, unlike my nursery, wainscoted clumsily in some dark wood, and with cupboards and bedsteads, and chairs, and benches placed about it. The beds were, I thought, all empty, and the room itself without anyone but myself in it; and I, after looking about me for some time, and admiring especially an iron candlestick with two branches, which I should certainly know again, crept under one of the beds to reach the window; but as I got from under the bed, I heard someone crying; and looking up, while I was still upon my knees, I saw you–most assuredly you–as I see you now; a beautiful young lady, with golden hair and large blue eyes, and lips–your lips–you as you are here.

“Your looks won me; I climbed on the bed and put my arms about you, and I think we both fell asleep. I was aroused by a scream; you were sitting up screaming. I was frightened, and slipped down upon the ground, and, it seemed to me, lost consciousness for a moment; and when I came to myself, I was again in my nursery at home.

Your face I have never forgotten since. I could not be misled by mere resemblance. _You are_ the lady whom I saw then.”

It was now my turn to relate my corresponding vision, which I did, to the undisguised wonder of my new acquaintance.

“I don’t know which should be most afraid of the other,” she said, again smiling–“If you were less pretty I think I should be very much afraid of you, but being as you are, and you and I both so young, I feel only that I have made your acquaintance twelve years ago, and have already a right to your intimacy; at all events it does seem as if we were destined, from our earliest childhood, to be friends. I wonder whether you feel as strangely drawn towards me as I do to you; I have never had a friend–shall I find one now?” She sighed, and her fine dark eyes gazed passionately on me. Now the truth is, I felt rather unaccountably towards the beautiful stranger. I did feel, as she said, “drawn towards her,” but there was also something of repulsion. In this ambiguous feeling, however, the sense of attraction immensely prevailed. She interested and won me; she was so beautiful and so indescribably engaging.

I perceived now something of languor and exhaustion stealing over her, and hastened to bid her good night.

(Chapter Two)

Reveal answer

You might have come up with one of the following elements, or others of your own:

- The domestic setting and wholesome girlhood friendship that yet somehow seems unsettling

- The portrait of Cleopatra bitten by her asp seems an unsuitable choice for a child’s room and strikes a note of jeopardy and death

- The eerie recognition of these hitherto strangers

- The shared dream

- The mixing of the familiar childhood bedroom with strange dreams and visitations

- The literal monster under the bed

- The mixture of the platonically affectionate and the erotic

- The scene is uncanny because of its presentation of the girls as unsettling mirror images, uncanny twins. As Patricia Coughlan explains: “Carmilla is of an age with the heroine. They share, and have shared before Carmilla arrived, the same dreams. They do not resemble each other physically but are represented as two halves of a pair: Carmilla’s dark colouring is the pendent to Laura’s fairness, her vivacity to Laura’s meekness; and her predatory nature to Laura’s submissive one.” (p. 151)

- Le Fanu constantly emphasises their equivalence, noting how they are of ‘like temperament’, ‘strangely drawn together’ (Carmilla p. 260). Both feel powerful and erotic connection: ‘with gloating eyes she drew me to her, and her hot lips travelled along my cheek in kisses; and she would whisper, almost in sobs, ‘You are mine; you shall be mine, and you and I are one for ever.’ (Carmilla, Chapter 4). Carmilla is thus the mirror image, the repressed double of Laura’s psyche. In a uncanny doubling they form a unity - Laura represents the wholesome and homely, Carmilla the repressed unheimlich - alien, monstrous, illicit and representing dark unsettling desires.

Vampire - Edvard Munch's painting. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Vampire - Edvard Munch's painting. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Part 1: Conclusion

In this article, we have traced many of the tropes prevalent in contemporary Irish Gothic writing, showing how eighteenth and nineteenth-century Irish Gothic fiction, from Carmilla to Dracula, established popular elements of Gothic from hauntings and monstrous villains to fairy stories and melodramatic peril. You have also tried your hand at creating a monstrous character and responding to a Gothic image as a way of finding your own Gothic voice and inspiration.

In The Irish Gothic in the twentieth and twenty-first century you will go on to look at how Gothic writing changed in the twentieth century – how Irish writers remain central to it and how Gothic has continued to evolve in response to the anxieties and challenges of today's world. Looking at examples from short stories, novels and plays, you will explore how Ireland has, in many ways, been haunted by its past and the pattern of recurring violence and cross-community tensions that have troubled the island over the course of the past century. In this sense, Ireland’s Gothic literature may even be said to represent its own historic doppleganger, or divided self. What also becomes clear in these texts, however, is the way in which evolving Irish identity and new literary elements, including humour, contribute to the creation of a distinctively modern Irish Gothic literary tradition in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Read on to learn more about Irish writing and get a chance to develop your own writing skills further.

References and further reading

Blackwell Baines, C (2025) How to Build a Haunted House London: Profile Books

Bowe, N.G. (2012) Harry Clarke: his life and work. Revised edn. Cheltenham, UK: The History Press.

Burke, E. (1796) The sublime and beautiful. By Edmund Burke, Esq. With an introductory discourse concerning taste, and other additions. Oxford: Printed and sold at the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, Glasgow, St. Andrews, Aberdeen, and Dublin.

Coughlan, P. (2011) ‘Doubles, shadows, sedan-chairs and the past: The ghost stories of J. S. Le Fanu’, in Crawford, G.W., Rockhill, J. and Showers, B.J. (eds) In a glass darkly: essays on J. Sheridan Le Fanu. New York: Hippocampus Press, pp. 137–160.

Crawford, G.W., Rockhill, J. and Showers, B.J. (eds) (2011) In a glass darkly: essays on J. Sheridan Le Fanu. New York: Hippocampus Press.

Croker, T.C. (1825) Fairy legends and traditions of the South of Ireland. London: Thomas Davison.

Curtin, J. (1890) Myths and folk-lore of Ireland. Boston: Little Brown. Reprint, New York: Weathervane Books, 1975.

Freud, S. (1955) ‘The “Uncanny”’, in Strachey, J. (trans.) The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. XVII. London: Hogarth Press, pp. 217–256.

Griffin, G. (1827) Holland-Tide; or, Munster Popular Tales. London: W. Simpkin and R. Marshall.

Haslam, R. (2014) ‘Maturin’s Catholic heirs: Expanding the limits of Irish Gothic’, in Morin, C. and Gillespie, N. (eds) Irish Gothics. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137366658_7. (Accessed 10/10/25)

Helmers, M. (2020) ‘Harry Clarke, the master of the macabre’, The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies, (18), pp. 77–308.

Jacobs, J (1892) Celtic Fairy Tales David Nutt

Jentsch, E. (1997) ‘On the psychology of the uncanny (1906)’, Angelaki, 2(1), pp. 7–16.

Killeen, J. (2013) The emergence of Irish Gothic fiction: history, origins, theories. 1st edn. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3366/j.ctt9qdrh2. (Accessed 10/10/25)

Killeen, J. and Morin, C. (eds) (2023) Irish Gothic: an Edinburgh companion. 1st ed. England: Edinburgh University Press Ltd. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781399500579. (Accessed 10/10/25)

Le Fanu, J.S. and Costello-Sullivan, K. (2013) Carmilla: a critical edition. 1st edn. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Longueil, Alfred E. (1923) “The Word ‘Gothic’ in Eighteenth Century Criticism.” Modern Language Notes, Vol 38(8) 1923, pp. 453–60. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2915232 (Accessed 29/10/25)

MacAndrew, E. (1979) The Gothic tradition in fiction. New York: Columbia University Press.

Morin, C. (2020) ‘The Gothic in nineteenth-century Ireland’, in Gothic in the Nineteenth Century. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 359–375. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108561082.017. (Accessed 10/10/25)

Morin, C. (2018) The Gothic Novel in Ireland: c.1760-1829. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Perrault, C (2012) Classic Fairytales of Charles Perrault Gill & Macmillan

Shelley, M.W. (2014) Frankenstein. 1st edn. New York, NY: Open Road Media Integrated Media.

Signorotti, Elizabeth. (1996) ‘Repossessing the Body: Transgressive Desire in Carmilla and Dracula.’ Criticism Vol 38(4) pp.607-32.

Stoker, B. (2020) Dracula. New edn. Edited by R. Luckhurst. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

White, L. and Andrews, H. (2009) ‘Harry Clarke’, Dictionary of Irish National Biography. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3318/dib.001703.v1. (Accessed 10/10/25)

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews