Irish Yews and part of the extensive graveyard, Holme upon Spalding Moor - Wikimedia Commons

Irish Yews and part of the extensive graveyard, Holme upon Spalding Moor - Wikimedia Commons

This article will explore the Gothic tradition on the island of Ireland in the form of the twentieth-century narrative. Building on the significant reputation for Gothic writing established by the end of the nineteenth century (explored in An introduction to the Irish Gothic), Irish writers took this tradition in new directions in the twentieth century. They responded to the seismic changes associated with modernity, from rising nationalism to new developments in psychology. The international upheaval of two world wars actively shaped the work these writers were producing, but the social and political upheavals of Irish politics at home—from the Easter Rising to the Troubles—contributed to a truly distinctive form of Gothic writing produced in Ireland.

You will be looking specifically at two examples of this writing: the short story ‘The Demon Lover’ (1945) by Elizabeth Bowen and the play The Weir (1997) by Conor McPherson. You will also be invited to engage with some optional creative writing exercises, giving you the opportunity to work on spooky ideas of your own.

Both writers make use of some well-established Gothic tropes and familiar themes such as the supernatural and fantastical but also bring the Gothic to bear on new everyday domestic settings and introduce distinctly new elements to create a twist on the Irish literary tradition. Their work demonstrates the way in which the twentieth century intensified some of the influences of Gothic from the nineteenth century, but also created some of its own.

Influences on Irish Gothic Writing in the Twentieth Century

Conflict: domestic and abroad

The twentieth century was a time of great conflict for Ireland, both domestically and abroad, which resulted in a sustained period of social and political uncertainty. Alongside the upheavals of the Great War and Second World War, Ireland itself faced revolution at home, with the Easter Rising in 1916, a violent War of Independence from 1919 to 1921, and a bloody Civil War from 1922 to 1923. Ireland was divided in North and South and the unresolved issues contributed to the outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland in 1969, The Troubles only concluding with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. The fear of violence was a constant accompaniment to life in Ireland over the course of the century and, in many ways, Gothic writing developed in response to it.

The political instability of previous centuries also continued to haunt Irish society and contributed to something of a national identity crisis. As Kevin Whelan puts it, “In Ireland the appeal to the past inevitably worried old wounds on which the scar tissue had never fully congealed.” (p.34) The forms and focus of Irish Gothic writing developed in response to these factors: the ornate melodrama of eighteenth and nineteenth century Gothic made way for existential dread and national trauma experienced on the level of everyday life. Commentators agree that the focus of twentieth-century Irish Gothic writing moved to a ‘ domestic scene […] predicated on loss’ (Whelan p.34). This had a direct impact upon the setting of twentieth-century Irish Gothic fiction: there is a move from larger-than-life castles to the familiar everyday domestic settings that readers can identify with. The settings and action of these stories may feel more plausible, closer to home, but they lose none of their ability to frighten or unsettle.

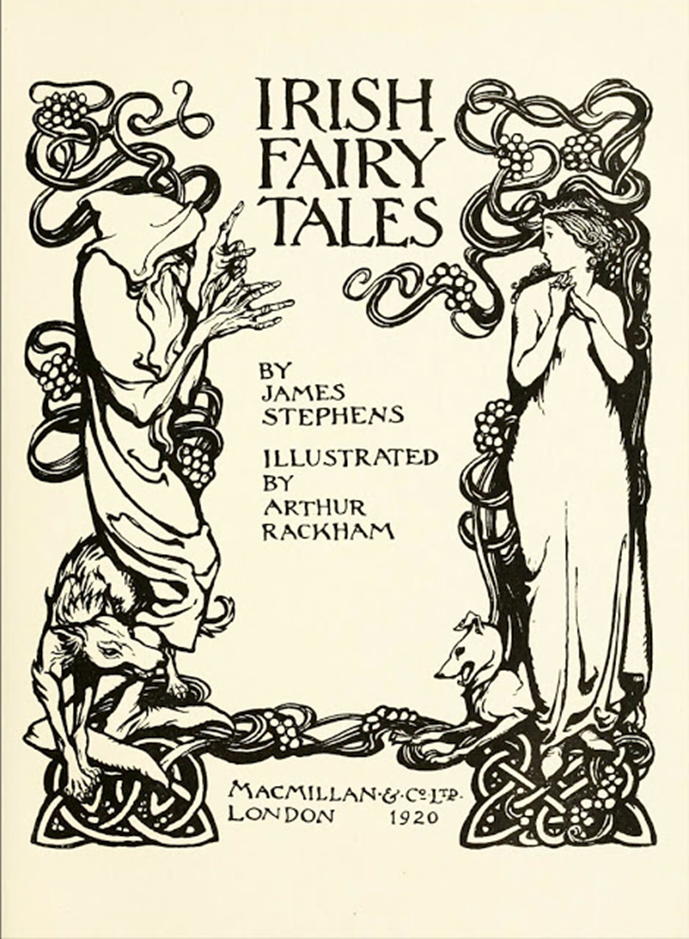

Title page from Irish Fairy Tales - Wikimedia Commons

Title page from Irish Fairy Tales - Wikimedia Commons

The Irish Revival

The Irish Revival took place at the latter end of the nineteenth and into the start of the twentieth century. This was the name given to a national push to celebrate and reclaim Irish heritage and identity. This movement highlighted the distinct differences between Irish and British culture, encompassing everything from language, sports, music, history and of course literature. This revival conspicuously emphasized Irish folklore and myth, often in opposition to the modernity of industrial Britain. In many ways this revival heralded a golden age of Irish writing, inspiring writers such as W.B. Yeats and James Joyce. In the twentieth century, Irish Gothic writing still regularly explored folklore and mythology: fairies, giants, tricksters, heroic warriors and deities frequently make an appearance, as the examples below make clear.

Fairies - Francis Danby - Wikimedia Commons

Fairies - Francis Danby - Wikimedia Commons

The Rise of Spiritualism

The rise of Spiritualism, mediums and seances was originally triggered by the Fox sisters' 1848 claim of communicating with a ghost in America. This generated a widespread movement across America and Europe. Interest in communicating with the dead became extremely popular over the course of the nineteenth century and then was reinforced at the beginning of the twentieth century with the universal grief of the Great War. In Ireland, the influence of Spiritualism was most notably visible in the works of William Butler Yeats and other figures of the Irish Literary Revival, endeavouring to access a distinct Irish spiritual identity. Famous Irish mediums of the early twentieth century included Kathleen Goligher (1898 – 1972) from Belfast, and Dublin born Eileen J. Garrett (1892-1970).

Kathleen Goligher and Eileen J. Garrett

Kathleen Goligher and Eileen J. Garrett

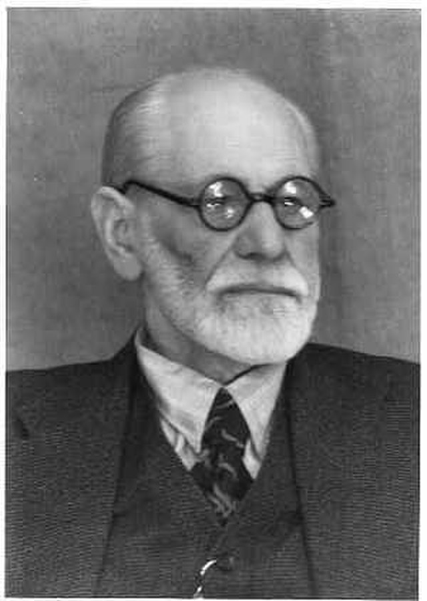

Post Freudian world

It is hard to overestimate the impact of new developments within the field of psychology on twentieth-century Gothic writing, in Ireland and further afield. As the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939), in particular, was responsible for much of our modern beliefs around systems of psychology. From the Oedipus complex to dream analysis and repression, Freudian concepts have had a profound impact on literature. By introducing the concept of the unconscious mind, Freud radically transformed writer’s understanding of their craft, inspiring the creation of psychologically complex and layered characters. Freud’s influence became foundational to modernist and postmodernist literature, opening new avenues for exploring human motivation, desire, and the hidden dimensions of psychological experience. Evidence of this movement can be found in both twentieth and twenty first century Irish Gothic fiction and is particularly highlighted in the work of Irish novelist and short story writer Elizabeth Bowen.

Photograph of Sigmund Freud - Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of Sigmund Freud - Wikimedia Commons

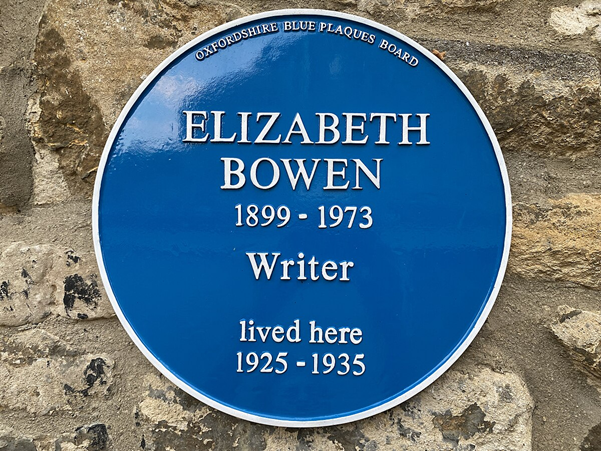

Elizabeth Bowen – The Demon Lover (1945)

Photograph of Elizabeth Bowen - Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of Elizabeth Bowen - Wikimedia Commons

Elizabeth Bowen (1899-1973) was a prolific writer, known for her short stories, novels, and non-fiction writing. Bowen was particularly acclaimed for her ability to capture the mood of London during the Blitz, the unique sense of living in perpetual fear and risk associated with war-time conflict. This was, as outlined above, a fear with which the Irish were familiar. A member of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy, Bowen explored life as an aristocratic Irish woman in an independent Ireland and war time London. Although she was never fully at home in either setting, she used this sense of displacement in many of her works. There is a use of realism in her writing which, when served up with a Gothic edge, introduces the uncanny into the urban domestic lives and settings of women.

One of her most famous ghost-stories is ‘The Demon Lover’ (1945) You might like to take a few moments to read it here. If you are not familiar with the story or would like to refresh your memory of its plot, here is a basic summary.

Basic plot

In this iconic short story set during the Second World War, we are introduced to the character of Mrs. Drover, who has returned to her London house to collect items for the country estate where her family is staying for safety during the Blitz. Here she finds a mysterious letter waiting on the hall table for her, despite the fact that the property has been sealed up. Few details are provided but it’s clear that the letter links her back to her youth and to promises she made to a former lover, a soldier in the Great War who was reported missing and presumed dead. The letter, signed K, contains a reminder of a prearranged meeting to occur that very day, despite no dates being included. It refers to an hour arranged, with no reference to an exact time. There is an immediate mystery here, which Mrs. Drover is not willing to entertain, but which clearly scares her to the core. How did the letter appear in the sealed property? Who is K? And is it possible that he will arrive before the clock strikes the next hour?

Setting the Scene: Location, Location, Location

Let’s read the opening paragraph of the short story to get a sense of how Bowen creates the creepy atmosphere that grows continuously over the course of the story:

“At the moment the trees down the pavement glittered in an escape of humid yellow afternoon sun. Against the next batch of clouds, already piling up ink dark, broken chimneys and parapets stood out. In her once familiar street, as in any unused channel, an unfamiliar queerness had silted up; a cat wove itself in and out of railings, but no human eye watched Mrs. Drover’s return.” (p.1)

From the opening of the short story, Bowen develops a sense of unease. The scene is vivid, a domestic setting of 1940s London that would be familiar to both Mrs. Drover and the contemporary reader, and yet something is clearly ‘off’ from the start, the scene is overlaid with ‘unfamiliar queerness’ which puts the reader immediately in edge – it hooks us in. There is something unfamiliar and akilter in Mrs. Drover’s neighbourhood, a location that should feel safe. The road that was once familiar is familiar no longer, having been made nearly unrecognizable by the destruction of bombing. This offers us a twist on the common early Gothic trope of the abandoned space. Here we encounter, not the crumbling castle or abandoned manor house of the nineteenth-century Gothic, but rather the empty streets of a city under attack.

Bowen uses her language choices to build up a sense of the uncanny. There is an impression that nature is behaving in an unnatural and furtive way. She personifies the clouds, as if they were some unknown entity—'they pile up’--and the sun appears to be trying to ‘escape’ through them. The reference to the cat, which appears right after the repetition of ‘familiar’ in the previous sentence, is suggestive of witchcraft. Because of their proximity to human owners and to the domestic scene, cats and dogs often feature as elements of the uncanny in Gothic fiction. And if, as we are told, ‘no human eye’ watched Mrs. Drover’s return, the reader is forced to wonder who is telling this story? Is it something inhuman? All of these elements makes for an unsettling introduction to Mrs. Drover’s world.

The arrival of the mysterious letter introduces a further element of unease that begins to grow as the story proceeds. What leads to the crisis, or climax of the story, is a progressive deterioration of Mrs. Drover’s psychological state in response to it:

“Through the shut windows she only heard rain fall on the roofs around. To rally herself, she said she was in a mood—and for two or three seconds shutting her eyes, told herself that she had imagined the letter. But she opened them—there it lay on the bed” (Bowen, p3)

We can see Bowen’s skill as she develops the complexity of the characterization, by providing an insight into the internal machinations of Mrs. Drover, the turmoil of her subconscious mind. This is further reflected in physical responses that show the reader her anxiety – shutting her eyes and then reopening them.

Whether Bowen is exploring her character’s outer world or her inner psychological world, setting the scene is key to the frightening effects she creates in her fiction.

Elizabeth Bowen blue plaque - Wikimedia Commons

Elizabeth Bowen blue plaque - Wikimedia Commons

The Weir by Conor McPherson (1997)

Now you will look at quite a different example of the Irish Gothic, from the second half of the 20th century, in the form of Conor McPherson’s play, The Weir (1997)

The Weir, OVO, St Albans, Oct 2011 - Wikimedia Commons

The Weir, OVO, St Albans, Oct 2011 - Wikimedia Commons

Conor McPherson (b.1971) is a world-renowned Irish playwright, screenwriter and director. His plays have been performed from the Westend to Broadway, garnering a variety of awards.

His works repeatedly return to the theme of the Gothic, for example his play The Veil (2011) features a priest running a séance in an Irish house, while his adaptation of Daphne DuMaurier’s short story The Birds (2009) tells the story of a small town terrorised by the strange behaviour of the local avians. His screenplay, Eclipse (2009), is a ghost story centring on a widowed teacher living in County Cork.

Like many Irish writers before him, McPherson borrows from the past and exploits the uncanny in the everyday to play with the fears of his audience. But his brand of ghost storytelling also adds new elements that reflect a later twentieth-century Irish perspective. He deftly weaves the supernatural with humour, for example, and plays with new forms of Irish mythmaking: the rise of the Celtic Tiger, with all of the social and financial promise of Ireland in the late 1990s, proved fertile ground for a new wave of writing in Ireland. As Matthew Fogarty observes, ‘the Gothic is, after all, a genre that draws much of its potency from the anomalous conjunctions that bind the future to its past’ and in McPherson’s work, he asserts, ‘“horrendous pasts” and “glistening futures” make for eerie bedfellows’(p.17).

If you have time, you may want to watch a performance of The Weir here.

If you do not have the time to watch it in full right now or would like to refresh your memory of the plot, you will find a basic outline below.

Basic Plot

The one act play takes place in a small, rural remote County Leitrim pub, where four men try to impress a newcomer, Valerie from Dublin, by sharing ghost stories. Brendan is the barman, and the patrons are Finbar, Jim and Jack. The characters share a series of experiences in the form of monologues, which delve into Irish folklore, local superstition, the supernatural and personal loss. Something in the sharing of these stories, told with the backdrop of a storm, changes the lives of everyone present. Each story has its own arc; beginning, middle and ambiguous end, changing the tone of the pub gathering from jovial in the outset, to foreboding and sombre in its parting. However, it is Valerie’s tale that forces them to reconsider their own experiences.

This first-person format of the storytelling is familiar to readers of Gothic fiction, recalling examples such as Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1898), where the story is retold by a single character to a gathering around the fire on Christmas Eve. This point of view is effective because it automatically builds a level of trust.

One of the strongest elements of McPherson’s writing is his ability to capture an authentic Irish voice. There is a naturalism in the dialogue that draws the reader in, particularly reflected in the recognisable register of pub banter. His work reflects the universality of the world around him, and by making the characters familiar and relatable, he transports us into the plausible moment.

The use of a single location set draws the audience directly into the room: all of the dialogue takes place in the pub in real time. As with Bowen’s The Demon Lover, something is clearly amiss early on. McPherson’s dialogue ensures that the scene is relatable and yet charged with the possibilities of the supernatural.

Task 1

Read the following extract from The Weir – how does McPherson create a sense of the uncanny here, putting the audience on edge? (1997 p24-6)

Extract

“FINBAR. So ‘What kind of trouble?’ I says. And she says she was after getting a phone call from the young one, Niamh, and she was after doing the Luigi board, or what do you call it?

VALERIE. Ouija board.

FINBAR. Ouija board.

JACK. ‘Luigi board!’ She was down there in the chipper at Carrick, was she, Finbar?

FINBAR. Ah fuck off. I meant the Ouija board. You know what I meant. She was after being down in...

JACK. ‘The Luigi board.’

FINBAR. She was after, come on now, she was after being down in a friend of her’s house or this. And they were after doing the... Ouija board. And she phoned her mother to come and collect her. They said they were after getting a spirit or this, you know, and she was scared, saying it was after her.

And I obviously just thought, this was a load of bollocks, you know? If you’ll...excuse the language, Valerie. But here was the mother saying she’d gone and picked her up. I mean, like sorry, but I thought it was all a bit mad. But on the way back they’d seen something, like the mother had seen it as well. Like a dog on the road, running with the car and running after it.”

Reveal answer

In this extract, McPherson makes use of the mythological figure of the ghostly black dog, otherwise known as the grim, Black Shuck, Padfoot, or Gaidhrin Caointeach. In folklore, the sight of the hellhound is often seen as the ominous harbinger of death.

The conversational tone and humour at the start of the play puts us at ease, then the rug is pulled from under our feet by the mention of the Ouija board, spirits, and the black dog. The quick cut between conversation humour and supernatural horror, when played out in the already charged context of a nearly empty rural bar in a wild storm, soon makes the reader uneasy.

McPherson’s use of humour in this scene hints at a longer tradition within Irish gothic fiction of using laughter to hide painful or fearful emotions. As Irish novelist Charles Maturin put it in his iconic pact-with-the-devil narrative, Melmoth the Wanderer (1820),“A mirth which is not gaiety is often the mask which hides the convulsed and distorted features of agony--and laughter, which never yet was the expression of rapture, has often been the only intelligible language of madness and misery. Ecstasy only smiles--despair laughs.”

Interior of a pub - Wikimedia Commons

Interior of a pub - Wikimedia Commons

Future ghosts and monsters to come: Twenty-First Century Irish Ghost Fiction

In this final section of the article, you will move forward to the twenty-first century, to examine the contribution of three contemporary writers to the tradition of the ghost-story in Ireland: Jess Kidd, A.M. Shine and Jan Carson. By looking at these narratives, you will consider how the history of the Gothic tradition continues to inspire Irish writers, who use it as a vehicle for responding to events close to home as well as broader developments in the modern world.

Short Stories by Jess Kidd

“You have come in the pursuit of knowledge. Wishing to probe the very secrets of nature, finger the mysteries of life and death, verily, to assume the role of God. You want to set your quivering hands upon tomes ancient and occult!” ("Lily Wilt" by Kidd, 2022, p.124)

Image of a ghost, produced by double exposure in 1899 - Wikimedia Commons

Image of a ghost, produced by double exposure in 1899 - Wikimedia Commons

These words from Jess Kidd’s 2022 short story ‘Lily Wilt’ get to the crux of why readers are attracted to the Gothic genre: perhaps they too are ‘Wishing to probe the very secrets of nature, finger the mysteries of life and death’ (p.124)?

Kidd grew up in London, as part of a large family from County Mayo. She is also the author of four novels, along with short stories, often with a Gothic twist. From Victorian mystery Things in Jars (2019), to Himself (2016) set in the rural and remote west coast of Ireland.

She has been nominated for several awards including the CWA New Blood Dagger, the Authors' Club Best First Novel Award and the Kerry Group Irish Novel of the Year Award.

Ghostly elements consistently appear in her work but her style of writing and thematic interests range widely. In her short story ‘Lily Wilt’ (2022), for example, Kidd delves into the nineteenth-century traditions of the Gothic ghost story then gives it a postmodern twist. This is a rich, opulent and vividly wrought Gothic tale in the vein of many of the writers to whom you were introduced in the previous part of the collection. In contrast, we are now going to look in more detail at another of her short stories that has a far more contemporary, pared back feel: ‘Dirty Little Fishes’.

Photograph of a graveyard - Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of a graveyard - Wikimedia Commons

You can read or listen to this short story here.

Basic Plot

In ‘Dirty Little Fishes’, we are introduced to a young Irish girl who is visiting a dying woman in London with her mother. The patient, whom the girl names ‘Nearly Dead’ lies prone on the sofa. ‘She’s as flat as the pelt of a run over cat. Propped up in a little nest of cushions with her face turned towards the fish tank. Her eyes sleep under closed lids, soft blind eggs. Her mouth is a slack pocket. Otherwise her face is a pale flower and the tank is her sunlight.’ Whilst her mammy is in another room talking to Nearly Dead’s husband, inanimate objects around the room begin to stir to life and speak with the girl, including a model of a mermaid in a fish tank.

By the end of the story, Nearly Dead is truly dead and regains her real name, Rita. Our narrator continues to communicate with the mermaid, causing upset at the wake by smashing the fishtank to rescue her, before she resiliently goes out to play, giving Rita the imaginary happiness she deserves.

Like Bowen before her, Kidd brings the focus to a contemporary domestic setting: the front room of an ordinary house. The room she finds herself in is familiar, however the presence of the silent patient and elements of dreamlike magical realism create a sense of the uncanny. Everything about this situation, from the way her mother and the man are interacting in the kitchen, to the personification of the ornaments, is off. At first thought, you’d imagine this was simply a case of childish imagination, and Kidd effectively captures the voice of the narrator by focusing on childlike observations and language. However, the animated ornaments seem to have access to some greater intuition than our narrator, as evidenced by the following passage:

“‘I wouldn’t touch her,’ murmurs the mermaid. ‘You’ll get what she’s got.’

‘I didn’t touch her, I only touched her buttons.’

The mermaid sweeps her hair over her shoulder and narrows her eyes. ‘Tell him she wants to hear music. Tell him she wants Shirley Bassey.’

She turns on her tail and swims down to her stone sending the little electric fish darting everywhere. She sits with her back to me and I watch her bubbles rise and pop on the surface of the water.” (Kidd n.d)

Kidd uses showing over telling (exposition) to great effect in this short story. An effective piece of writing is one that understands the balance between what the reader is told directly—known as ‘exposition’—and what is merely hinted to the reader, forcing them to read between the lines. Telling the reader something directly can cut time and word count, skimming over unimportant details, whilst showing, though it might use a longer word count, can have more impact because the reader has to make sense of what they have been told. Using a balance of both showing and telling allows the writer to decide which aspects of the story can be summarized, and which need lingering on more fully.

Elements such as the relationship between Mammy and Nearly Dead’s husband are merely hinted at. The reader is never explicitly told but joins the dots to come to the conclusion that they are in a relationship of some kind. We are never told whether the mermaid is really alive or a figment of the girl’s imagination. As readers we must make that decision for ourselves. The overall effect is deeply unsettling. We may wish ‘to probe the very secrets of nature, finger the mysteries of life and death’ (‘Lily Wilt’ Kidd p.124) but Kidd does not provide the reader with any concrete answers.

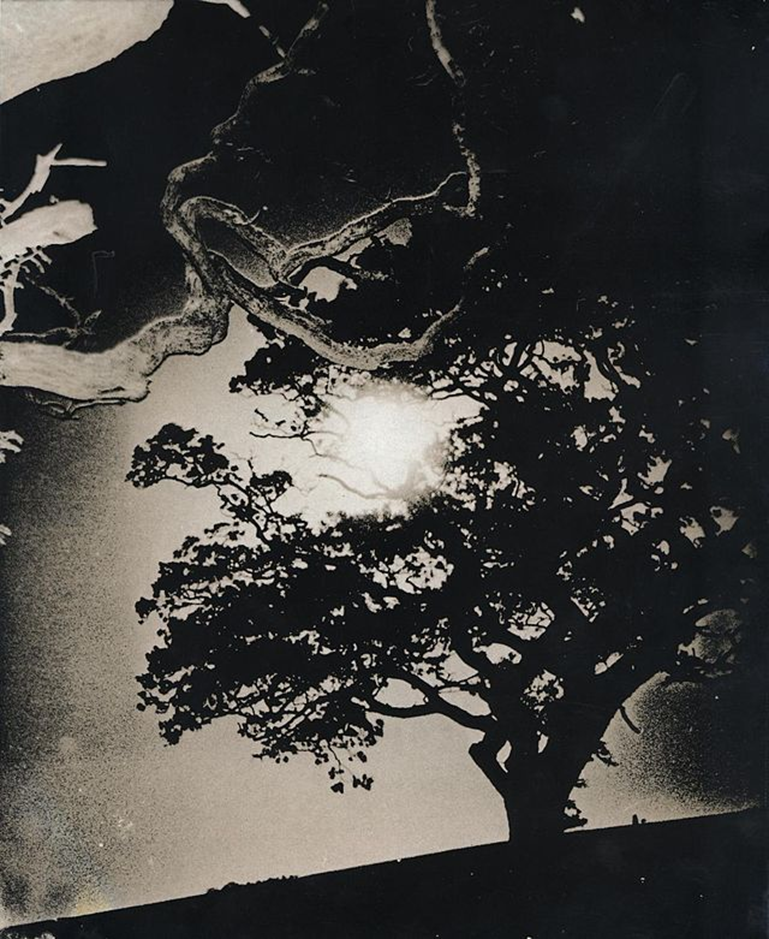

A.M Shine and Folk Horror in The Watchers (2022)

Black and white photo of a tree and shadows - Wikimedia Commons

Black and white photo of a tree and shadows - Wikimedia Commons

A.M Shine is a novelist from Galway in the west of Ireland. Describing himself as a ‘writer of Irish Horror’ he explicitly lays claim to an Irish Gothic tradition, noting that his work is ‘influenced by his country’s culture, landscape, and language[, drawing] their dark atmosphere and eloquence from the Gothic canon of his past.’ (Shine n.d).

In his debut horror novel The Watchers (2022) and its sequels, The Creeper (2023) and Stay in the Light (2025), Shine directly explores Irish settings and traditional folklore but brings to it a distinctly twenty-first set of references: among other things, he uses our relationship with technology as a mechanism for creating tension and suspense.

You may have heard of The Watchers, a film adaptation directed by Ishana Night Shyamalan, and produced by M. Night Shyamalan (2024)

Basic Plot

Mina, an artist, is haunted by her own past, unable to commit to the future and on the run from the present. She is adrift from society and in this way already quite alone. One day she is paid cash in hand by an acquaintance to deliver a tropical bird, by car, to a mysterious buyer many miles away. Along the way, the winding road travels through a dense and endless forest. Inevitably, it would seem, her car breaks down and things go from bad to worse when she leaves the car looking for help. She is soon lost and disorientated, having lost sight of the road completely. As the sun goes down, she comes across three strangers trapped within a concrete bunker, sheltering from the unknown creatures who come at night to watch them.

You may recognise some familiar Gothic tropes here: a woman in peril, a dark secluded location, a trap sprung. But here Shine delves into folk horror, asking us to redefine what makes a monster. The novel leans directly into Irish myth and tradition: there are no flower fairies here! The creatures are powerful shapeshifting supernatural beings, identified with the original inhabitants of Ireland and tired closely to the natural world. The result is something that feels simultaneously indulgently Gothic, but also contemporary and horrific.

Task 2

How does Shine use language and setting effectively to create a feeling of tension and danger in the following extract from The Watchers?

Extract

“The storm lasted for two days and nights. The gale howled loudest through the living room’s bare frames, throwing nature’s wreckage into the corners, and spinning dry ash and whirlwinds across the floor. Branches split and fell. Some hung on by the flailed sinew of ivy and through tangled knots of thorns. The rain was relentless, breaking around the tree in waves, making their old wood creak like a fleet of sinking ships” (Shine P87)

Reveal answer

Shine makes use of several senses in this extract, ensuring the reader has an insight into the sound of the storm and the feel of the cold whistling through the walls. The wind is actually personified: it is said to ‘howl’, which is what we associate with a predatory animal. Tree branches become bodies held together by ‘sinew of ivy’ and ‘knots of thorns’. There is no actual mention of cold, but the overall effect of the living room and its ‘bare frames’ is of a creature with all of its clothing and protective layers torn off. There is a sense of foreboding, which is echoed by the doom-laden simile of ‘a fleet of sinking ships.’ Shine creates tension through the isolation of the characters and the threat to their safety, as if they were adrift on the sea. The sentences are short and punchy, creating pace and tension.

Lochwood Oaks - Wikimedia Commons

Lochwood Oaks - Wikimedia Commons

Jan Carson and The Raptures (2022)

Jan Carson is a writer from Northern Ireland whose short stories and novels have been translated into over 15 languages. Her novel The Fire Starters won the EU Prize for Literature for Ireland 2019, and her novel The Raptures was shortlisted for the An Post Irish Novel of the Year, the Dalkey Book Prize and the Kerry Group Irish Novel of the Year Prize in 2022. Some of Carson’s work engages directly with Gothic tropes and characters: The Fire Starters, for example, features a Siren, the mythical sea creature ; traditionally blamed for luring sailors to their deaths. Much of her work features more general tales of peril and loss, as in her short story collection Quickly While They Still Have Horses (2024), where “a distracted couple on a beach fail to notice their baby crawl perilously towards the sea”, “a rumour spreads at a public swimming pool and chaos ensues” and “a dishevelled father loses his two sons in an adventure park”. (Carson) Her writing draws on what it means to be Irish in the modern age, whilst living alongside the ghosts of the past.

Photograph of Jan Carson - Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of Jan Carson - Wikimedia Commons

Here is a plot summary of The Raptures:

Basic Plot

The Raptures is set in a rural village in Northern Island in the early 1990s. The novel opens at the start of the summer holidays, but what should be a time of fun and relaxation for the local school children quickly turns to tragedy. The community is shocked as one by one the children begin to die from a mysterious illness. Whilst the adults begin to panic, speculating on the link between the string of deaths, one child, Hannah, is visited by the ghost of each of her school mates within hours of their passing, often before the death has even been announced.

At its heart, The Raptures is a mystery, but one that brings rural Ireland uncannily to life through elements of magic realism. Carson takes the familiar and safe setting of the village and its school and makes it simultaneously dangerous and threatening. This is a story about the impact of loss and trauma on Irish communities, echoing the inherited trauma and conflict of the Troubles.

Task 3

Read the extract below and spend 5 minutes thinking about what techniques Carson uses in this passage to show us the ways in which the present can be haunted by the past. At this point in the novel’s action, Hannah is speaking to the ghost of her classmate Kathleen for the first time:

Extract

“I’m dead so I am,’ Kathleen announces. She waits for Hannah to react and, when she doesn’t, motors on, ‘It’s not as bad as you’d think. I’ve never been that scared of dying myself. Sure, you really can’t be, if you’re from here. Because of the Troubles, I mean. Anybody could get killed at any time. You know my mum, got blown up when I was wee?’

Hannah nods. She knows about Kathleen’s mum. Everybody in Ballylack does. Kathleen’s never done talking about it. She thinks having a blown-up mum makes her some kind of celebrity.

‘I don’t remember Ma at all, only the funeral and the baby coffin they put her in. Granny shouted at my dad, “For God’s sake Stephen, did you have to be so cheap?” and he was all “What’s left of her wouldn't have filled the toe end of a proper coffin.” After the funeral he moved to Ayr. That’s in Scotland, by the sea. Sometimes I wish he’d taken me with him. Anywhere’d be better than Ballylack. Anyway, like I was saying, I’m totally used to death.” (Carson pp.55-56)

Reveal answer

Firstly, and most obviously, there is a very literal haunting taking place in this scene: Hannah encounters the ghost of Kathleen, a classmate who has clearly died but is appearing to her and speaking in quite a natural and informal way.

But there is also a metaphorical haunting at work in this passage. It becomes clear that Kathleen is, herself, haunted by the death of her mother in the Troubles and the circumstances around it. In fact, Kathleen reveals that she has lost not only her mother, but also her father, who abandoned her after her mother’s funeral. The reader may find it uncomfortable that all this information is offered in an easy conversational tone, suggesting that Kathleen is quite comfortable with her change in circumstances. Indeed, she tells Hannah that she is ‘totally used to death,’ implying that the experience of losing her mother means she found the transition from life to death a straightforward one. The trauma of the Troubles and their violence is further downplayed by Kathleen’s casual recounting of the conversation between her Granny and her father about the unexpected size of her mother’s coffin. The effect is darkly comical, recalling the tradition of humour in Irish Gothic writing, which often relies on the juxtaposition of laughter and fear to create its effects and to generate the tension we associate with the uncanny.

Playground, recreation ground and village green - Wikimedia Commons

Playground, recreation ground and village green - Wikimedia Commons

Conclusion

This article has traced many of the tropes prevalent in contemporary Irish Gothic writing, all the way back to authors from the eighteenth century through to the twenty-first century. Although the genre has inevitably been influenced by a wide range of social, political and developments over time, it is clear that writers in Ireland have adapted and shaped it in unique ways that continue to inspire readers both in Ireland and across the globe.

An Introduction to the Irish Gothic showed how eighteenth and nineteenth-century Irish Gothic fiction, from Carmilla to Dracula, established popular Gothic elements, such as hauntings, monstrous villains, and melodramatic peril out of a context of political instability and health precarity. The Irish Gothic in the twentieth and twenty-first century has demonstrated the way in which a distinctive brand of Irish Gothic writing has continued into the twenty-first century, transformed to reflect not just the legacy of Ireland’s past but also the anxieties and promise of the current moment. . In this sense the Irish ghost story tradition may even be seen to function as a kind of doppelganger for Ireland itself, a dark mirror of its history and thrillingly suggestive of a future yet to unfold.

As we have explored in this resource, the Irish Gothic tradition has long had an inward focus on Irish identity, history, and politics, particularly through the exploration of psychological and social anxieties. Add to this a rich history of mythology, the beauty of the landscape and the diversity of its people, and you have the perfect recipe for the evocation of fear and suspense.

Looking forwards, we continue to see the influence of the Gothic narrative coming to life in new and unusual ways, for example in computer games, such as The Seance of Blake Manor – also using Ireland as it’s setting and drawing on well-known tropes and folklore.

References and further reading

Bowen, Elizabeth (1945) ‘The Demon Lover’. UNC Greensboro. Available: 7.-Bowen-The-Demon-Lover.pdf (Accessed 29 September 2025)

Bram Stoker Dracula (1872) Edinburgh: Archibald Constable and Company.

Carson, Jan (2023) Moving Mountains. Available: BBC Radio 4 - Moving Mountains by Jan Carson, Episode 1 - The Lord Mayor (Accessed 29 September 2025)

Carson, Jan (2024) Quickly While They Still Have Horses London: Doubleday UK.

Carson, Jan (2022) The Raptures. London: Doubleday.

Carson, Jan (n.d) The Last Resort. BBC Radio 4. Available: BBC Radio 4 - The Last Resort - Available now (Accessed 30th September 2025)

Carson, Jan (n.d) Jan Carson. Available: Jan Carson (Accessed 29 September 2025)

Brown, Curtis. Conor McPherson (n.d) Available: Conor McPherson - Curtis Brown (Accessed 29 September 2025)

‘Elizabeth Bowen’. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Elizabeth-Bowen (Accessed 29 September 2025)

‘Elizabeth Bowen, the 'grande dame' of the modern novel,’The Guardian (15 Feb 2017) Available: Elizabeth Bowen, the 'grande dame' of the modern novel - archive, 1960 | Elizabeth Bowen | The Guardian (Reprint of an article from The Guardian Archive, 15 February 1960) (Accessed 29/09/25)

Fogarty, M (2018) ‘“Most foul, strange and unnatural”: Refractions of Modernity in Conor McPherson's The Weir’. Irish Gothic Journal, no. 17, pp. 17-37, 209. Available: 'Most foul, strange and unnatural': Refractions of Modernity in Conor McPherson's The Weir - ProQuest (Accessed 29 September 2025)

Kidd, Jess (2023) Tide Witch BBC Radio 4. Available: BBC Radio 4 - Short Works, Tide Witch by Jess Kidd (Accessed 29 September 2025)

Kidd, Jess (n.d) ‘Dirty Little Fishes’ Jess Kidd. Available: Dirty Little Fishes | Jess Kidd (Accessed 25 September 2025)

Kidd, Jess (2022) ‘Lily Wilt,’ The Haunting Season. London: Sphere Publishing.

Killeen, Jarlath (2020) ‘Irish Gothic Fiction’, in L. Harte (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198754893.013.2 (Accessed 14 July 2025)

Maturin, Charles (1820) Melmoth the Wanderer Edinburgh: Archibald Constable and Company.

McPherson, C (1997) The Weir London: Nick Hearn Books.

Perrault, Charles (1697) Histoires ou contes du temps passé. Paris: Claude Barbin.

Shyamalan, Ishana Night (Director). (2024) The Watchers [Film]. Blinding Edge Pictures; Inimitable Pictures

Shine, A.M (n.d) ‘About A.M Shine’. A.M. Shine, Writer. Available: About — A.M. Shine (Accessed 29 September 2025)

Shine, A. M (2023) The Creeper. London: Bloomsbury Press.

Shine, A. M (2025) Stay in the Light. London: Bloomsbury Press.

Shine, A. M (2022) The Watchers. London: Bloomsbury Press.

Shultz, Matthew (2018) ‘‘Give it Welcome’: Gothic Inheritance and the Troubles in Contemporary Irish Fiction’. Irish Gothic Journal. Available: Matthew Schultz.1 (Accessed 29 September 2025)

Whelan, Kevin (1996) The Tree of Liberty: Radicalism, Catholicism, and the Construction of Irish Identity 1760–1830. South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, p. 37.

Wiegand, Chris (20 September, 2025) ‘The Weir Review: a riveting return for Conor McPherson’s lonesome barflies’. The Guardian. Available: The Weir review – a riveting return for Conor McPherson’s lonesome barflies | Theatre | The Guardian (Accessed 29 September 2025)

Wild, Oscar (1891) The Picture of Dorian Grey London: Ward, Lock and Company

Wyver, Kate (2018) ‘The Weir Review: Conor McPherson’s black stuff still chills’. The Guardian. Available: The Weir review – Conor McPherson's black stuff still chills | Theatre | The Guardian (Accessed 29 June 2025)

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews