Writing for The Telegraph in 2018, Prime Minister Boris Johnson described Muslim women wearing a niqab (face veil) as looking like ‘letter boxes’ and ‘bank robbers’. Fast forward to 2020, and amidst a global pandemic public health advice to wear a mask to limit the spread of Coronavirus becomes a matter for political debate, with politicians and public alike slow to accept the advice that face coverings are a necessary part of the prevention strategy (Ahmad, 2020; Mueller, 2020). Given the vilification of the niqab as symbolic of oppression and subjugation, not only in the UK but across Europe, it is no great leap to suppose that perhaps some of the reluctance to widely adopt face coverings could be tied to the negativity towards veiled women which has often dominated political and public debate.

Discussions of the veil form just one aspect of my research which looks into embodied intersectionality across everyday spaces of home, work and public spaces for British South Asian (BSA) Muslim women. What do we mean by embodied and intersectionality, and why might these be useful concepts to think about when we study the experiences of ethnic minority communities?

Embodied differences

Let’s start with embodied or embodiment. To embody is to represent an idea or quality exactly, and in relation to the body, whereas embodiment is the process or state of living in a body. Our bodies are uniquely connected to our sense of self, but also how we relate to or understand our social world. How we move through and interact with our physical environment, react to, or are seen by others, are all interactions experienced by and through our bodies. For some bodies, often through their perceived differences which are read on the body, the ways they are seen can be through a lens which is clouded with stereotypes or misconceptions.

It is the reacting to and being seen by others which is a key element of my research and I ask a number of related questions: What happens when Muslim women’s bodies are only understood through the stereotypes about them? How and in what ways do Muslim women challenge these stereotypes? How do Muslim women negotiate a sense of self across the different spaces which feature as part of their everyday lives?

What is intersectionality?

In order to answer the questions discussed above we can use the concept of intersectionality. What is intersectionality, and how can it help us make sense of different bodies? Intersectionality is a concept which looks at how a person’s different social categories/identities such as race, gender, ethnicity, religion, culture, ability/disability, sexual orientation and others can intersect or overlap to create different experiences of discrimination or privilege and different patterns of advantage or disadvantage.

First coined by Kimberle Crenshaw (1989, p. 65), a theorist in the USA, Crenshaw explains that intersectionality can be understood as a metaphor. Imagine an intersection, or crossroads through which traffic will flow in a number of directions, likewise ‘discrimination, like traffic through an intersection, may flow in one direction, and it may flow in another’ simply considering one form of discrimination is not enough to understand how certain groups can be disadvantaged against.

So, we have to look at the way social categories may intersect and overlap to create multiple discriminations and apply this to looking at the way BSA Muslim women experience the everyday. This is because, as research shows, Muslim women do not simply experience discrimination based on gender, race, ethnicity or religion, rather the way these social categories overlap in different spaces, such as work or public spaces, becomes key to understanding Muslim women’s lives and everyday experiences.

Embodied intersectionality

How do these concepts, embodied and intersectionality fit together? What is embodied intersectionality? Let’s refer back to what we mean by embody/embodiment; we’ve already discussed how certain stereotypes can become attached to certain bodies, and how this in turn affects how those bodies are seen. How might this affect veiled BSA Muslim women?

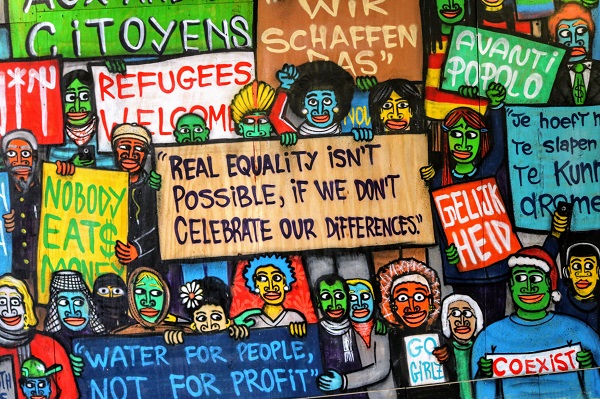

Well, what are some of the first images that come to mind when you think of Muslim women and the veil? Take a few minutes to think about what the figure of the Muslim woman has come to represent, what common words or perceptions come to mind? Don’t worry, this doesn’t have to be a reflection of your own views but might be from the impressions you get from media, culture or politics.

Some of these impressions might be ‘foreign’, ‘Other’ or unable to speak English, of a particular ethnicity or culture; these stereotypes can become attached to certain bodies, so in turn these bodies both embody and become the embodiment of these differences. In short, as my research discusses, the niqab has become the embodiment of Muslim women’s and by extension Muslim communities ‘otherness’. This can have an impact on the everyday lives of Muslim women, as ‘stereotypes are powerful forms of knowledge’ (Mirza, 2013, p. 112) this affects not only the way Muslim women are seen but in turn how they see themselves.

This manifests in different ways across spaces, for example, a niqab-wearing research participant in a supermarket recalls:

Cashiers and people don’t really tend to talk unless I speak first, they ignore you, like the other day I was in Sainsbury’s, I was putting stuff in bags, the cashier speaks to my husband usually, unless I say something first they just assume I won’t talk. They assume you’re a suppressed housewife, or typical Asian who doesn’t speak English, or someone who doesn’t want to integrate.

Here the research participant discusses being made to feel invisible as the cashier does not directly engage with her but speaks with her husband instead. Embodied intersectionality allows us to analyse how stereotypes framing the Muslim woman as ‘silent and oppressed’ can impact on interactions for Muslim women. The lack of interaction between the research participant is framed by the way she is seen, or most notably by the ways in which she is not seen. The niqab embodies as representing lacking in English skills, an unwillingness to interact or integrate, and niqab-wearing Muslim women then become the embodiment of these characteristics so that although she is not seen, what she embodies is. Thus, eventually Muslim women are only understood under these stereotypes; they become non-persons (Goffman, 1959) and reduced to what the veil represents.

BSA Muslim women experience Islamophobic physical and verbal abuse, with niqab wearing women over-represented in statistics on religiously motivated hate crime. What my research also discusses is the way embodied intersectionality impacts on the way BSA Muslim women are seen and the ways in which they see themselves.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews