6.5 Appreciating some implications for practice

I think for most people, the National Health Service would be experienced as a complex situation. If so this would be a good example of perceived complexity. Remember though, if you engaged with it as if it were a difficulty you would not describe the situation as one of perceived complexity. I could not call it a complex system unless I had tried to make sense of it using systems thinking and found, or formulated, a system of interest within it. This means I would have to have a stake in the issue – an interest. In systems terminology, I would need a purpose for engaging with the ‘real-world’ situation. When I do not have such a purpose in mind, I am using the word system in its everyday sense rather than in its technical, systems practice, sense.

The fundamental choice that faces both systems theorists and complexity theorists is choosing to see system or complexity either:

-

As something that exists as a property of some thing or situation; and that, therefore, can be discovered, measured and possibly modelled, manipulated, maintained or predicted; or

-

As something we construct, design, or experience in relationship to some thing, event, situation, or issue because of the distinctions – or theories – we embody.

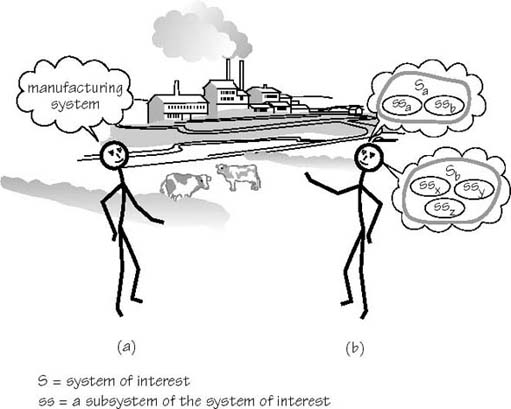

There are profound differences between these two options, as I have tried to depict in Figure 20.

These epistemological choices depicted in Figure 20 determine the nature of the engagement – the E ball – of a systems practitioner with a ‘real-world’ situation. The first choice says a lot about the nature of the thing or situation but says little about the practitioner concerned with the thing or situation. This is the situation where technical rigour, of the type described by Schön in his quote in Section 6.2 above, informs practice. Schön describes this as technical rationality in which there is a radical separation of research – and what is regarded within this epistemology as legitimate knowledge – and practice.

The latter position however, has a lot to say about the practitioner and about what they know and are able to do, as well as about their relationship to the thing or event they experience. In this situation the systems practitioner is engaged with the complex situation. He or she must construct or design alone, or with other stakeholders, the system of interest and choose to see the situation as complex or simple, mess or difficulty.

Taking responsibility for the choice you make about these two distinctions is an act of being epistemologically aware. The aware systems practitioner recognizes that a system of interest is an epistemological device, a way of creating new ways of knowing. The course is designed to help you develop your skills in being aware as part of your systems practice. At this stage, all you need to do is to note your reaction to my claim about being epistemologically aware. Do you recognize something of what I mean or does it seem quite meaningless and unnecessary? I anticipate both responses, so don't worry if you fall into the latter category. I have already introduced the basis for my position in this section.

Let me emphasize here, making a choice of one epistemological position or another in a given context is not an act of discarding or deciding against the other position – it is an act of being aware of the choice you made. Both positions offer rich explanations of phenomena in different contexts.