5 Questions, questions

5.1 How did we get here?

We began this course by posing the question: what is a crime? Shouldn't we be finishing with a clear and unambiguous answer to this? Well we are sorry to disappoint you, if that is what you were expecting, but it doesn't look to us as if there is a simple, unambiguous answer. At the very least, according to Sections 1 and 2 of this chapter, there are: legal and normative definitions of crime; recorded and unrecorded crimes; the crimes we fear and the crimes that fascinate us; and stories of crime and facts about crime. But even this last pair breaks down, for as we know from Section 2, stories of crime in the contemporary UK carry as much weight and as much importance as facts about crime like the official crime rates. And the facts are themselves complex social constructions which cannot be taken at face value.

What is available to us are a range of contested definitions, descriptions and narratives of crime within the social sciences and amongst society at large. And what that says to us is not that we have an adequate answer, but that we need to start asking some more, and some better questions.

So the story of this chapter has been about how one moves from one set of questions about the social world to a new and better set of questions. How did we do that? Let's stand back for a moment and think through the process by which we arrived at our tentative questions and conclusions.

Activity 10

You should be familiar with flow diagrams by now. If not, look at Figure 1 which shows how a hypothetical event might be processed through the criminal justice system.

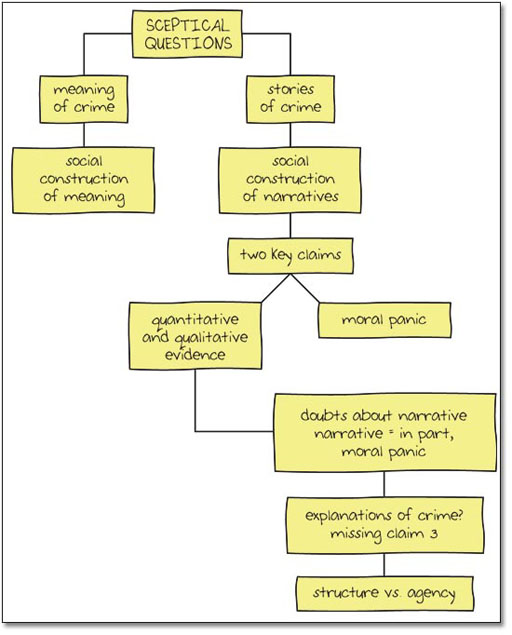

Try and construct a flow diagram for the stages of argument that we have gone through: the questions which have been asked, the response of the authors, and the development of the argument. Don't spend too long on it, it only needs to be a sketch. Or use a flow diagram program.

Then compare your diagram with ours.

So, we began with the question: what is a crime? By analytically breaking down the definition of the word, its popular uses, and the process that exists between acts and convictions, we concluded that there is no objective, universal standard of human behaviour which clearly distinguishes between criminal and non-criminal behaviour. One of the main ideas introduced at this point to help us understand how certain behaviours and activities come to be defined as criminal was the idea of crime as a social construction.

If the definition of crime is not simple, are our narratives about crime any more reliable? We know that there are popular, common-sense stories of rising crime, insecurity and uncertainty, and a popular taste or fascination with crime and criminals. These were outlined in Section 2. We also noted that these stories are premised on an assumption of a relatively crime-free and socially-harmonious past, contrasted with a present characterised by rising degeneracy and falling moral standards.

The first stage in developing a social scientific approach to these narratives was to clarify their core claims (Section 3). Stories are often too big and unwieldy to examine as a whole. Once again, we needed to analytically break down the stories and dig out their central claims. Only then could we bring on some evidence which might support the popular common-sense claims, or cast them in a different light.

Evidence can come from a variety of sources. Quantitative evidence, in the form of official statistics, appeared to give some support to the common-sense story. But, as soon as we began to think about how the evidence was collected, and by whom, doubts set in: the crime rate has actually been falling in recent years, there are grounds for thinking that the rise in crime is due to greater reporting rather than greater numbers of crimes, and it all depends on what type of crime you are looking at, etc. Evidence never speaks for itself and it never arrives innocently into the world.

Qualitative evidence, which recognises the context and meaning of crimes for those involved, came in the form of victim reports and surveys on the experience of crime and the fear of crime. One of the most important pieces of evidence was the survey which showed the more at risk people are from crime (in general statistical terms given their age and gender), the less they fear it; and the less at risk they are, the more they fear it. However, even this was complicated by issues of class and geography. So irrespective of what the official statistics might say, it may be that our fascination with crime is fuelling our story-telling.

We took this one stage further in Section 3.4 when we applied the idea of a moral panic to the crime problem. While not conclusive in any way, our discussion suggests that popular concerns with crime may function as metaphors and ways of speaking about a whole series of other social changes and uncertainties in our society. Evaluating this idea would require a whole new set of questions and claims, evidence and argument.

The claims of the common-sense story that we tested against the evidence in Section 3 were descriptive claims about how the world was and how the world is now. What they did not deal with is how we got from one to the other. To link these together we need an explanatory claim. There are many different explanations of why people commit crimes, and therefore many potential explanations of the rise in recorded crime.

Rather than looking at the claims of politicians or common sense, we took a step back to look at social science explanations (explanations which are drawn upon by politicians, the media and the public, in conscious and unconscious ways). Again this was an analytical task. Before we could begin to compare these explanations or examine them against the evidence, we had to break them down, to establish their core explanatory claims.

In the final Activity of Section 4 we thought a little about what the process of comparing explanations might involve and came back to a new set of questions and concerns. They certainly suggested that simple accounts of the decline of community and demoralisation which accompany many common-sense narratives about the crime problem need developing.