2 Inclusive Leadership and collaborative enquiry

In Video 1 in Activity 1, one of the participants said that professional development was helpful ‘As long as we are part of groups that have identified the needs of a school.’ A reason for this is that having agreed the needs of a setting, you can then collectively explore possible ways forward. An aim for many leaders is to make such exploration part of the school’s culture. Miles, Ainscow & Moore (2011) situate a culture in the basic beliefs and assumptions shared by people in an organisation, which operate unconsciously and through which people view themselves and the contexts in which they work. They also suggest that effective, inquiry-based approaches require an element of challenge, involving new thinking and relationships that encourage active connections between people, stimulating risk taking and creative actions. The development of inclusive practices requires social learning within particular cultural contexts. ‘Developing’ people involves providing intellectual stimulation and using information to create a culture of inquiry. This calls for making interruptions to people’s thinking, to challenge existing assumptions and practices.

These ideas are evident in a piece of research looking at two elementary school principals in the United States (DeMatthews, 2021). This work explored how the principals sought to create an effective inclusive school, as well as what they saw as the challenges and necessary change processes. These school leaders saw a need to focus their collaboration, relying upon a group of staff to explore school challenges, to decide on priorities and initial steps as well has how to problem solve specific problems that emerged from chaotic everyday school life. Their first step in establishing their ways of working was to develop routines where staff regularly collaborated. They set up teams of five to seven-people who regularly met and developed plans for change. The principals looked for quick wins and small steps, rather than focussing upon what they viewed as bigger issues. At the heart of their approaches was collaborative inquiry. They recognised that time was needed to develop the structures to enable this, given people’s already busy daily workload and the need to consider multiple variables and perspectives to implement inclusion effectively. This fitted with their understanding of inclusion as an ongoing process. As a result, they focussed on specific goals to begin with; for instance, in the first-year prioritising how to support marginalised students they felt could be immediately successful in general education classrooms, whilst providing professional development on co-planning and co-teaching. They also encouraged collaborative inquiry as a way to deal with individual issues that emerged, gathering a group to work out what was going on. They sought shorter feedback loops, to explore problems and proposed solutions. They recognised that there was a need for open communications and ensuring people had access to information, and for responses that were both effective and as quick as possible.

So, let’s consider some of the ways in which collaborative enquiry can take place in a school.

Activity 3 Better than one?

Read: Harris, A. and Jones, M., (2012) ‘Connecting professional learning: Leading effective collaborative enquiry across teaching school alliances [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ’, National College for School Leadership, UK.

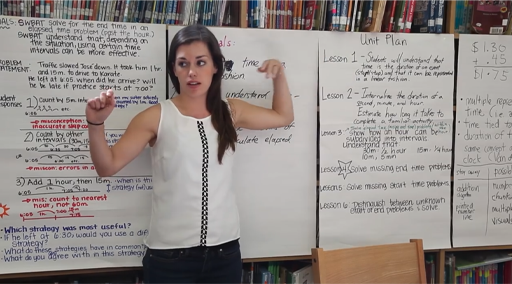

Read the Appendix 1, pp. 38–39. This text outlines four approaches (Learning walks; Instructional rounds; Peer triads; Lesson study). You can find out more about these approaches by searching online if you wish to; there are lots of resources out there, even though they can often give contradictory advice! Included here are some resources. Video 2 includes mention of OFSTED, the school inspection service in England.

Transcript: Video 2 Learning walks: what are they?

Video 3 is a more collaborative approach.

Transcript: Video 3 Learning walks: structured observation for teachers

Transcript: Video 4 Lesson study: a powerful approach to improve teaching

- Text 1: Instructional rounds

- Text 2: Teachers in Triad Teams: Three is not a crowd (The Open University is not responsible for external content.)

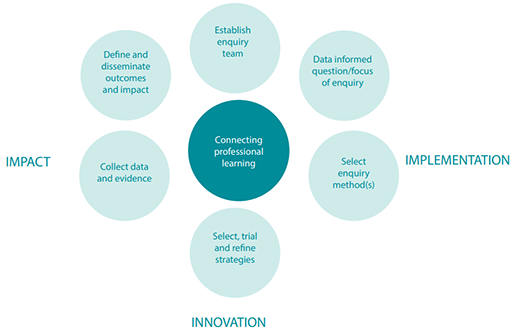

Having considered these approaches, study this image of the connect to learn method from the report by Harris and Jones? Ask yourself the following questions?

- Who might be in an enquiry team?

- What sort of data could they use?

- What sort of enquiry methods are you aware of?

- What sort of issues do you think could be explored this way?

- Who would you want to disseminate findings to in a school community?

Discussion

Looking across a range of examples, it is clear that enquiry teams are very often made up of practitioners exploring their own practice, but as the work by Schenke et al (2016) discussed above makes clear, such teams could also include school leaders, researchers, and advisers. It is also commonplace to include administrative staff in such activities, and also learning support staff. Less frequently do people choose to include other staff in the school, such as those involved in maintenance or food preparation, but there is no reason why they should not. They would certainly bring new insights and understandings. Another group worth considering are the young people in the school. We will return to these possible team members in the next activity.

The nature of data is also more variable than you might have felt at first. In many of the online resources explored in developing this activity, data was seen as something hard and fast. It was a target, something that could be measured or had been agreed on as the focus prior to the activity. But data can be understood in many other ways. In the first Learning Walks video listed above, the school leader talks about a member of staff who has had a mishap. This is an example of an anecdote from someone’s life as data. Stories, opinions, ideas, notes, pictures, memories, are all powerful data sources. This is one of the reasons for working with other people; if you have open discussions, you are far more likely to think about things “outside the box”. If you narrow your understanding of data, the danger is that the group is just ticking the same box alongside each other.

You may have thought of other formal approaches to collaborative enquiry, but in some ways the formality of the process can get in the way. In searching the internet for example, the course author came across a wide variety of ways to undertake all the activities listed above; however, many of the resources had a very strict method of undertaking the activity. Often these were associated with local standards or frameworks for practice. A more helpful way to think about methods is to view them as a third space (Hulme et al, 2009). Collaborative inquiry can be seen as a recognised place in which professionals can put aside the pressures of the workplace for a while, to think through practice. It can be seen as a navigational space, that serves to allow them to move between different personal and professional understandings of situations. It can be seen as a conversational space, in which competing knowledges and ways of thinking are contested, explored, and translated so a closer understanding can emerge.