4.1 A matter of internal politics?

Another paper which recognised the emotional work of change is Lindle et al, (2017). In their study of 17 Principals and District leaders in the United States, they talked about how emotions of leadership emerged as an influence upon the way in which professional development was experienced and undertaken. Issues such as budgets and state funding, local and national policy debates had a long-lasting effect on the participants, leaving many feeling both under-valued and under attack. In another study from Australia (Jones, 2017a) Female head teachers, described the gendered expectations around school leadership, and talked about how these overlapped with other assumptions around issues such as race, age, and family life.

‘The biggest cost is your stress levels- your immediate home life, family...social circle, you don’t have time for them…it’s so easy to get sucked into a vortex of work.’

Against such a background, these head teachers consistently constructed themselves as trying to be empathetic and supportive, seeking to enable the career progression of their staff.

Clearly the emotional work of leading, collaborating and personal development cannot be underestimated. So let us conclude by considering this a bit more deeply.

Activity 8 A matter of internal politics?

The following paper reports on three teachers collaborating as they investigate a program in the school of modern languages (FML) of a public university in Mexico.

Read Keranen, N. and Encinas Prudencio, F. (2014) ‘Teacher collaboration praxis: Conflicts, borders, and ideologies from a micropolitical perspective [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ’, Profile Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 16(2), pp. 37–47.

Read from Results (p. 42) to the end of conclusion (p. 45). As you are reading reflect upon a collaborative experience you have had in a workplace. Make notes in response to the following questions:

- How did you feel about yourself?

- How did you feel about others?

- How did these feelings enable or restrict your collaboration and achieving its goals?

- What other challenges did you find in working with others?

- How were you supported to deal with these issues?

Discussion

On reading this article it is striking how the first point of reference is self doubt. The notion of ‘imposter syndrome’, is far more prevalent than many of us might recognise. At the heart of imposter syndrome is an irony though; often, we feel we are the only ones experiencing it. It was helpful to see too that the act of being part of a professional development process can leave people feeling as if they are falling behind and exposed. You may also have recognised the response of these teachers and their wish to be seen to be making a contribution, which could be linked to this sense of not being good enough. At the same time, it was clear that there was an openness to their relationships and a willingness to change, as well as a mutual respect and acceptance of their contrasting approaches to an issue. This seemed a particularly important point; despite their tendency to compromise, these three professionals did not feel they were abandoning their creativity and control. It would appear, that at the heart of it all they still felt that they had agency.

It is interesting to consider these findings in relation to other studies. Philpott & Oates (2017), for instance, in their study of Scottish professional learning communities suggest that people need to explicitly articulate and be willing to critique their assumptions. They also benefit from detailed information on issues and from having a diversity of voices present. This includes moving beyond expert notions of knowledge towards discussions of such things as purposes, values, identities or relationships. These researchers recognise too that the process of professional development should be a proactive space for agency. It should serve to enable people to play an active part in the development and application of their professional learning and the space in which it occurs. Part of this process is to give people more time to work collaboratively with facilitators and critical friends to enhance their agency in the longer term. This underlines that the process of professional development is also a process of change for a person’s identity, as a leader, a practitioner and as a member of a wide variety of communities.

The issue of time and working with mentors was also acknowledged in an Australian study at a secondary school (Sharp, Jarvis & McMillan, 2020). Here the school leaders provided structural and administrative assistance to professional development, amending timetables to support collaborative planning. Practice development however was mostly driven by staff at middle management level, who facilitated changes in understandings and practices by discussing issues in departments meetings. It was also facilitated by working with a project lead acting as mentor. This mentor role proved more valuable for some staff compared to voluntary training sessions, because it was ongoing, practical, context specific and frequently part of informal everyday discussions. It was recognised that schools had to develop their own expertise, not simply relying upon external advisors, and create their own opportunities for professional conversations.

The reading in Activity 8 and the studies mentioned in the comment have not been directly about school leadership. However, they raise a variety of issues (and possible solutions) that seem to be relevant to the experience of collaborative development across contexts. Which brings us back to where this course started, and the need to form partnerships amongst key stakeholders as part of a whole school approach, with policies and practices arising from the experience and expertise of all those involved.

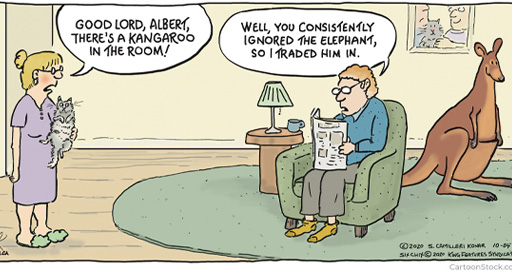

Hopefully, this course has made it very clear that at the heart of this collaborative process are openness, flexibility, authenticity, criticality, and agency. Hopefully it has also made clear that this is not a simple process. In developing our practices and systems, we are invariably faced by a need to have difficult conversations. These are not difficult because people have to listen to each other (see Figure 4.2), but because they are about our attitudes, beliefs, underlying values, and the ways in which we organise our lives and our institutions. The challenge for School leaders is to find ways to support people to have these conversations as part of their day to day working lives; and to do so in ways that do not feel top-down but emerge from the community they are intended to serve. This is where the kinds of professional development opportunities discussed in the previous sections may be of some use. What do you think?