5 What students say about learning to teach?

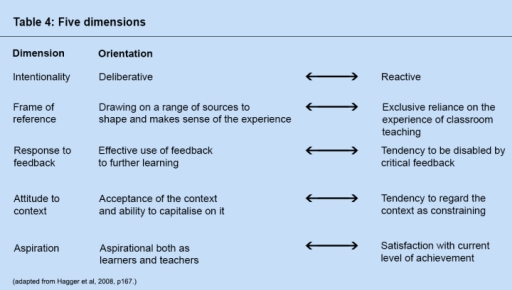

Hagger et al. (2008), in their longitudinal study of student teacher’s reflections on their learning, found that responses could be categorised into five dimensions:

What is particularly interesting about their research findings, is that student teachers themselves recognise the significance of their own responsibility as learners.

These ideas are reflected in a number of studies that examine student teachers own perceptions of themselves as learners.

Intentionality

As in Hagger et al’s research, Taylor (2008) found evidence of effective learning when students deliberately set their own schedules of learning and influenced the implementation of these. She found that, ‘Students achieve this through reflection on self in terms of their own individual development and of their development as teachers, and through reflection on wider educational theory.’ (Taylor, 2008 p. 79).

Interestingly, Mutton et al. (2010) found that student teachers identified a lack of power, meaning a lack of ability to influence or experiment with alternative approaches to teaching, as a potential constraint to effective learning. This could be seen to be a criticism of approaches to ITE that require students to replicate existing practice, such as Zeichner’s traditional craft paradigm (1983) or the transmission approach, but could equally be a criticism of student teachers who adopt a reactive approach to learning.

Frame of reference

Hagger et al. (2008) found that effective student teachers drew on a range of sources of information.

The value of other sources of learning isn’t overwhelmingly recognised in research that highlights student teacher’s opinions. Maldrez et al. recognise that some student teachers indicated that they felt such ‘theoretical’ studies were only of peripheral relevance (Maldrez et al., 2007). However, she did find evidence that some student teachers acknowledged that they might be using it ‘subconsciously’.

‘“I feel that things like learning about theories of how children learn and things are useful, but I can’t honestly say I’ve ever put them in my teaching… But maybe I do subconsciously, but I don’t know...” [Female, 20–24, BA QTS, secondary, MFL]’ (Maldrez et al., 2007, p. 235)

If considering this evidence to Zeichner and Taylor’s research, then it is possible to see that the Enquiry Orientation (Zeichner 1983) and development of students as teachers and learners (Taylor 2008), both promote a type of learning that draws on a wide range of sources.

Response to feedback

Caires et al. (2012), like Hagger et al. (2008), provide evidence that student teachers value the feedback they receive, if it supports effective learning. Caires et al. define effective feedback as ‘the sharing of experiences with their supervisors and other student teachers, the joint exploration of beliefs, perceptions and affects involved in teaching practice and/or the joint construction of meanings’ (Caires et al. 2012, p173). They argue that these can support effective learning as they lead to ‘self-exploration, exploration of the teaching profession, mutual knowledge and the strengthening of complicity relationships amongst student teachers, their supervisors and colleagues’ (Caires et al., 2012, p. 173).

Mutton et al’s research indicates that student teachers value feedback which raises questions and issues as much, if not more so, than being offered solutions (Mutton et al., 2010).

Reflection point: Why do you think the student teachers in Mutton et al’s research felt the way they did about feedback? How does it relate to the discussion of paradigms and approaches to ITE?

Attitude to context

Hagger et al. identify a difference between students who can capitalise on a context in order to learn, and those who see the context as a constraint (Hagger et al., 2008). This is reflected in Taylor’s research which found examples of students who were aware of the different opinions and opportunities that different contexts brought to their learning, as evident in the following quote:

… I think people need to be open-minded about the whole process, rather than thinking this is how I’m going to teach because when I first came onto the course I just had one view of teaching… However, I’ve been opened up to all these different ideas, working with my mentors and tutors, and also other students and other teachers … and you have to accommodate working with others so you’re always going to be learning and you’re always going to be learning different ideas [and] some of the things you learn, I didn’t always agree with, but I feel that you have to be completely open-minded and you have to try and change things. (Student 1)

Aspiration

Interestingly, aspiration, as defined by Hagger et al.(2008), concerns not only aspiration as a teacher but also aspiration as a learner. This is supported by Taylor’s research which identified that students ‘make connections between principle and practice, thought and action to make sense of teaching and its impact on education in general, schools and particularly children and their learning’ (Taylor, 2008, p79). In describing this dual, although fundamentally interlinked identity, Taylor discusses student’s development as both learner experts and expert learners.

This section has focused on what student teachers consider to be important to their learning. It is clear that those working with student teachers, their view of the learning process and attitude to ITE have a great influence on the effectiveness of the learning experience. However, Hagger et al’s research (2008) reminds us that central to effective student teacher learning is the attitude and approach of the student themselves. This will be influenced by the nature of the ITE course (i.e the paradigm or approach that underpins it, the route, level or qualification) but also the opportunities afforded to the students to take responsibility for their own learning.