2 Quantitative research

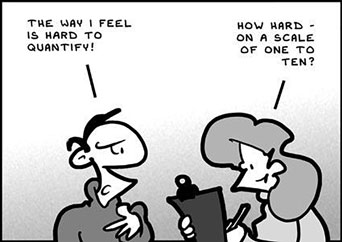

Quantitative research reflects the philosophical stance of ‘positivism’. Those who ascribe to this position believe a topic of research can be described, recorded and studied numerically in a scientific manner. In simple terms, they believe that it is possible to quantify and therefore measure, in a research context most aspects of life. For instance:

Basic descriptive statistics can often be used to describe a population by comparing, for instance, different age ranges. For example, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that around 15.1% of people aged 18 years and over in the UK have smoked cigarettes. Of the constituent countries and Northern Ireland, 14.9% of adults in England smoked; for Wales, this figure was 16.1%; Scotland, 16.3% and Northern Ireland, 16.5% (ONS, 2018).

Correlational analyses explore the relationships between factors or variables. For instance, there is a correlation between increasing obesity and increasing levels of socio-economic deprivation in adult women in Scotland, such that women in the most deprived areas of Scotland are more likely to be obese relative to women in the least deprived areas of Scotland. Among men in Scotland the results are less conclusive (Scottish Government, 2010).

Experimental research can be used to measure the effect of an intervention, that is, it can show the difference, if any, that a specific change has made. As an example, experimental research has shown that eating from plates with rims (specifically those with colouring to highlight the rim) exaggerates a person’s perceptions of food portions and tends to result in people (in particular children) eating less. This is a strategy that appears promising for improving portion control for children prone to over-eating (Robinson and Matheson, 2015).

According to Payne and Payne (2011) quantitative research does not explore social phenomena as they occur naturally, but instead involves introducing measures (such as questionnaires) or collecting data in a repeated and controlled way. Payne and Payne (2011) conclude that almost all forms of quantitative research share certain features:

- They describe and/or account for phenomena (e.g. aspects of human behaviour), in particular by using numbers (such as the number or proportion of people who engage in exercise regularly).

- They break down or separate behaviour into variables or factors that can be measured (for instance, by clearly defining regular exercise as ‘150 minutes of moderate intensity exercise in bouts of 10 minutes or more per week’).

- They contain statistical results that are analysed in a structured way (as an example, researchers have analysed the health benefits of the recommendation to get 150 minutes’ exercise, described above, in Saint-Maurice et al., 2018).