Find out about The Open University's Social Work courses.

Social workers write some of the most important records and reports about people’s lives, which have a lifelong impact (Pierre, 2022). Although writing is often mentioned as a burdensome sideline of what social workers do, writing and recording are core aspects of the practice of social work (Rai et al., 2024). The rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) has led to developments in social work writing. Findings from previous research into social work writing (Lillis et al., 2017) can help us consider the current opportunities and challenges that AI brings. Understanding the core elements of social work writing and how social workers learn to write effectively is crucial. Social workers need to consider how to use AI effectively in their writing without compromising their professional ethics and skills in analytical judgement.

What we know about social work writing

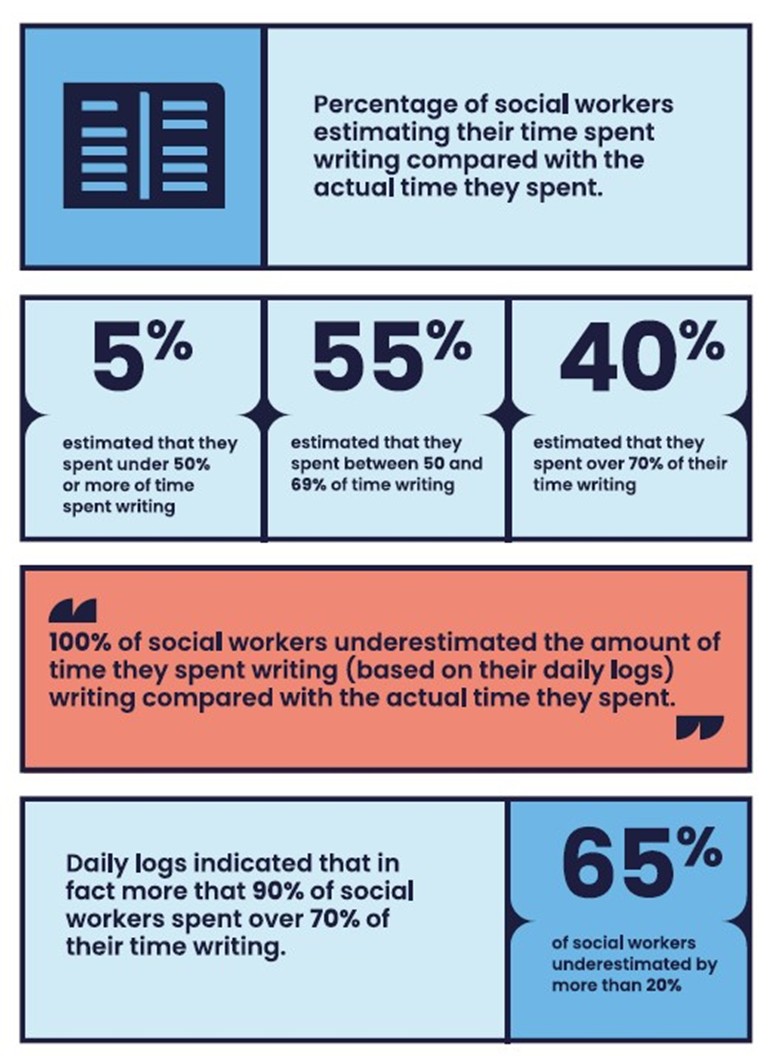

Writing occupies a huge amount of time in social work. The WiSP project explored exactly how much time social workers thought they spent and how much time they actually spent engaged in writing while at work. The image below shows that 40% of social workers said that they spent more than 70% of their time writing and 100% of social workers underestimated how much time they spent writing (Lillis et al., 2017).

Figure 1 Social workers estimated time spent writing compared to actual time spentAn infographic table is shown. In the top row an image of a notebook is in the left column. The words Percentage of social workers estimating their time spent writing compared with the actual time spent are in the right column. In the next row there are three columns. The first column has the words 5% estimated that they spent under 50% or more of time spent writing. The middle column has the words 55% estimated that they spent between 50 and 69% of time writing. The third column has the words 40% estimated that they spent over 70% of their time writing. The next row has the words 100% of social workers underestimated the amount of time they spent writing (based on their daily logs) writing compared with the actual time they spent. The final row has the words Daily logs indicated that in fact more than 90% of social workers spent over 70% of their time writing and 65% of social workers underestimated by more than 20%.

Figure 1 Social workers estimated time spent writing compared to actual time spentAn infographic table is shown. In the top row an image of a notebook is in the left column. The words Percentage of social workers estimating their time spent writing compared with the actual time spent are in the right column. In the next row there are three columns. The first column has the words 5% estimated that they spent under 50% or more of time spent writing. The middle column has the words 55% estimated that they spent between 50 and 69% of time writing. The third column has the words 40% estimated that they spent over 70% of their time writing. The next row has the words 100% of social workers underestimated the amount of time they spent writing (based on their daily logs) writing compared with the actual time they spent. The final row has the words Daily logs indicated that in fact more than 90% of social workers spent over 70% of their time writing and 65% of social workers underestimated by more than 20%.

Writing takes many forms from basic emails to case notes to formal reports for decision-making forums. There is much more to writing than simple recording of information; in particular, social workers’ texts are a powerful means to progress a case and ultimately reach the best available outcomes for service users. This power is enacted through social workers’ choice of words, through the selection of points to foreground or background, and through insightful evaluation, particularly within life-changing documents such as court reports. We should not forget the power of writing and that every word matters for the person who is being written about.

What we know about AI in social work

Many social work services have started to use generative AI systems and tools in the hope that this helps to manage pressured resources. Widespread use of new tools such as Magic Notes are now common with the aim of reducing the time needed and improving the quality of writing. Technological support in recording can be helpful but there are some challenges. Research shows that AI is not yet reliable in predicting risk or reflecting the nuances of language and context that are essential within social work practice (Gillon and Weaver, 2026; Haider et al., 2026). Social workers are dealing with highly sensitive data so there are also regulatory and legal issues to consider: where any data goes and how it is going to be used now or in the future are key concerns for people using social work services (Haider et al., 2026).

Social work is also rooted in challenging inequality and prejudice. There is evidence, however, that current AI systems and tools can reinforce and perpetuate bias – contrary to the mission of social work (Haider et al., 2026). This means there is a tendency to reproduce biases and eliminate diversity in all shapes and forms. What impact could this have on social work practices?

A person with black wavy hair and spectacles is in the left corner of the image with her hands open. A thought cloud is shown from the person’s mind which shows different icons of professional people.

A person with black wavy hair and spectacles is in the left corner of the image with her hands open. A thought cloud is shown from the person’s mind which shows different icons of professional people.

Of course, we’re not the first to raise concerns over algorithmic bias in AI tools. Is there a danger here of sacrificing principles for expediency? Curry et al. (2025) write convincingly about the problem of AI alignment with human values and intelligence. While writing about applied linguistics research, their points are – in our view – highly relevant to social work. For generative AI, ‘knowing’ is a product of processes built on probabilities and pattern recognition, and this has little to do with human knowledge-making. Perhaps most important – and worrying – is the generative AI inclination to standardise and simplify knowledge (Pragya, 2024).

Some other critical issues concern the ecological sustainability of AI in the context of the climate crisis (Reitmeier and Lutz, 2025), another key area of social work interest (Ferguson and Giddings, 2025). For a profession rooted in prevention of risk and harm, social workers have responsibility to protect and support people across the lifespan with climate issues directly linked to social and environmental justice (Ferguson and Giddings, 2025). What other issues might be important as AI continues to evolve?

Why writing matters as social work practice

Hopefully this article has shown that writing is a core part of the role of the social worker and that using AI is not a simple solution to do this task. Writing isn’t purely a means of recording what has been done or observed. It’s through writing that social workers process their thinking, communicate their values and build relationships with clients at a human level. Maintaining trust in social workers and other professions relies on human ethical practice. We need to continue to think of the ways that technology can help or hinder us at individual, local and global levels – all of which matters to social work.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews