10 Working-class distress and planned communities

Meanwhile Owen's views on the problem of poverty were also much influenced by his experience at New Lanark and had particular relevance to the difficult era that opened up after the Napoleonic Wars. Economic depression exacerbated growing problems of poverty and unemployment, and Lord Liverpool's government struggled against a rising tide of disorder, which was manifest in protests and riots. The relief of poverty, which had been a problem before, became a nightmare. While he may have had no personal objection to this, Owen could see that the contribution he and other property owners had to make to poor relief was bound to increase. Again he disseminated his views widely in a flurry of pamphlets published soon after the second edition of the essays.

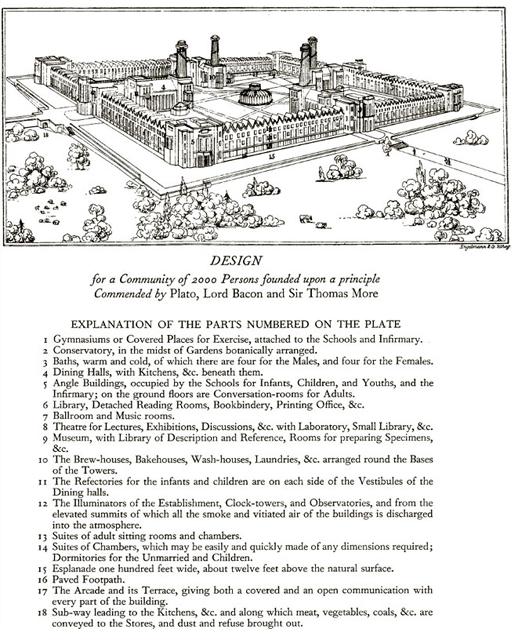

In 1817 Owen first proposed his ‘Village Scheme’, a plan that drew quite specifically on arrangements at New Lanark and the key ideas about social organisation set out in the essays. But unlike New Lanark the physical appearance of the proposed villages had a symmetry that more resembled military barracks built around a square located in plots of between 1000 and 1500 acres, which with careful husbandry would result in self-sufficiency. However, the new communities might combine agriculture and industry, rather like some planned estate villages of the period. The population was to be much as New Lanark's, comprising 1200 to 1500 persons, educated and employed according to their abilities and skills, and the scheme was to run at a potential profit once the capital cost of building had been recovered, an arrangement that has resonance today in public-private partnerships. You might be excused for thinking that this sounded like a workhouse, though this was not Owen's intention. However, sceptics were not long in voicing criticisms, as the following extracts show.

Exercise 21

Read the following extracts from Radical periodicals of the day. What is the tone conveyed and the writers' objections to Owen's scheme?

(a) [Owen] is for establishing innumerable communities of paupers. Each is to be resident in an inclosure, somewhat resembling a barrack establishment, only more extensive. I do not clearly understand whether the sisterhoods and brotherhoods are to form distinct communities, like the nuns and friars, or whether they are to mix together promiscuously; but I perceive that they are all to be under a very regular discipline; and that wonderful peace, happiness, and national benefit are to be the result.

(William Cobbett, Political Register, 2 August 1817)

(b) ‘Let Us Alone, Mr Owen’

Robert Owen, Esq, a benevolent cotton spinner, and one of His Majesty's Justices of the Peace for the county of Lanark, having seen the world, and afterwards cast his eye over his very well regulated manufactory in the said county imagines he has taken a New View of Society, and conceives that all human beings are so many plants, which have been out of the earth for a few thousand years and require to be reset. He accordingly determines to dibble them in squares after a new fashion; and to make due provision for removing the offsets. I do not know a gentleman in England better satisfied with himself than Mr Robert Owen. Everybody, I believe, is convinced of Mr Owen's benevolence, and that he purposes to do us much good. I ask him to leave us alone, lest he do us much mischief.

(William Hone, Reformist's Register, 23 and 30 August 1817)

Discussion

The tone is biting and satirical and the objections centre on the regimentation proposed in the new communities; whether or not discipline and good order will necessarily produce happiness; whether or not the well-regulated conditions of a factory can be replicated in the community at large; and, echoing Hazlitt, the claims that Owen had discovered new truths about human conduct.

The extracts exemplify the scepticism with which the Radicals greeted Owen's proposals. Of the two cited, William Cobbett (1762–1835), journalist and reformer, was the most scathing (elsewhere denouncing the proposed villages as ‘parallelograms of paupers’). Like Cobbett, Hone, a political satirist, concluded that Owen's scheme aimed to turn the country into a giant workhouse.

It is clear from the periodical press and from newspaper reports that Owen's schemes were equally mistrusted by the Radicals, Whigs and Tories, but thanks to his wealth and energy for self-promotion they received widespread publicity. He used his influence in places of power to advantage, especially among MPs, government ministers and wealthy people known to be of a humanitarian disposition, like his Quaker partners and their reforming friends. Both Sidmouth and Vansittart remained sympathetic and this encouraged others to look favourably on Owen's ideas. His views even attracted a measure of support from the upper levels of the British aristocracy, notably the royal Dukes of Kent and Sussex. It has to be said that Owen naively took the politeness of such persons as a commitment to act, when they were simply prepared to listen to a rich man who had some interesting solutions to the daunting social problems that threatened the established order and possibly their own class.

Nevertheless, in August 1817 many of his supporters turned out for a series of public meetings held in London when Owen explained his plan. But, showing an amazing lack of tact in the circumstances, he complicated his campaign by again attacking sectarianism in religion, a move which provoked further criticism and in the longer term alienated him from some potentially useful allies.

Soon a more millenialist tone expressed in the language of religion began to creep into the propaganda, and the communities proposed by Owen's plan were transformed into ‘Villages of Unity and Mutual Cooperation’. Competition was to be replaced by cooperation. However, he was careful to emphasise that equality could not immediately prevail and that social class (in four divisions), sectarian or religious affiliation and appropriate skills would be important criteria in the selection of personnel. He even appended a complex table showing all the possible combinations of religious and political sects to which future communitarians might conceivably adhere (Owen, 1972, pp.234–7).

Although there was no immediate prospect of the plan being taken up officially, Owen maintained a relentless campaign in which his success at New Lanark was continuously highlighted. The many visitors had spread its fame abroad and in 1818 he himself carried his message of his New System to Europe. He was preceded by 200 copies of A New View of Society, which (at least Owen says) Sidmouth had sent to the governments, universities and leading thinkers on the Continent, apparently inviting comments. Owen even claimed that Napoleon, exiled to Elba, had studiously read the essays and if given the opportunity would have devoted his life to implementing the New System. After staying in Paris, where he met senior members of the Bourbon government, had an audience with the Duc d'Orleans (later King Louis Philippe) and attended the French Academy, he moved on to Switzerland. Basing himself in Geneva he inspected several experimental schools, including Pestalozzi's, whose methods, as we have seen, were practised at New Lanark. Owen then headed for Frankfurt and later to Aix-la-Chappelle (Aachen), where two ‘Memorials on Behalf of the Working Classes’ that he had prepared and had translated into French and German were duly presented to participants at the Congress of the Great Powers, assembled to settle Europe's problems and neutralise the virus of revolution before it led to further war.

Owen refined his plan in further publications, notably his letters on the distressed working classes of 1819 addressed to David Ricardo, the political economist and MP, in which he spelled out the social and economic arrangements he thought would govern his villages. He also drew on examples from the United States where Moravians, Shakers and other religious sects had established successful communities. He specifically cited the example of Harmonie, Indiana, where a band of German Lutherans had built an apparently profitable cooperative enterprise, trading farm products and simple manufactures down the Wabash and Mississippi rivers as far as New Orleans.

These ideas were developed in later publications, notably the Report to the County of Lanark of 1820 (published 1821), where the principles of the essays were again restated and further details of plans for a trial of a community given. The report was followed by unsuccessful efforts to raise private capital and gain government support, both in Britain and in Ireland, which Owen toured in 1822–3, visiting places suffering hardship and holding packed meetings in Cork, Limerick and Dublin. These were attended by large numbers of women, some of whom evidently either swooned in his presence or were so overcome by heat that they had to be lifted through open windows to regain their composure. As elsewhere, he was accorded respect by the elite, including landowners and clergy (apparently of all denominations), but, as on the mainland, support was not strong enough to proceed. One final effort in 1824 to gain government support also failed, and by this time Owen had come to the conclusion that the New System stood a better chance of success in the New World (see Figure 10). Although British Owenites in the later 1820s made several attempts to establish communities based on the New System, Owen himself was not directly involved. Instead he crossed the Atlantic to inspect, and in 1825 finally purchase, what became known as New Harmony. The story of Owen's activities in the United States generally (1824–8) and Mexico (1829) takes us well beyond the texts of the essays and of New Lanark, but serves our present purposes in emphasising the international dimensions of Owenism and the strength of Owen's reforming mission and belief in his principles.

Reviewing the discussion in this course, we can see the relationship between the main ideas in Owen's essays and his plans for social regeneration. In particular, he focused on the strong links between people's environment, their education and social improvement. The problem of poverty was to be addressed through communities, whether agricultural, industrial or both, where mutual cooperation rather than individualism would prevail. This was sound enough so far as it went, but the major contradiction in Owen's use of New Lanark as a model lay in the fact that it was a business enterprise where profit was the driving force, albeit with model working and social conditions.