5 The background to the essays

5.1 The essays in context

Owen's public career effectively began in 1812, when he started to promote his ideas about popular education. He may have been thinking about this for some time. In 1810 he had evidently contacted Lord Liverpool (1770–1828), recently home secretary and by then secretary for war, about a proposed ‘Bill for the Formation of Character among the Poor and Working Classes’, aimed at establishing a national system of education. This object was a logical extension of Owen's experience among the workers at New Lanark, aligned to the possibilities of mass education under the monitorial system, which figures prominently in A New View of Society. Liverpool, understandably, was more concerned with defeating Napoleon than with popular education, and nothing came of the proposal. Owen may have been disappointed, concluding that his thoughts needed further clarification if they were to get anywhere in Parliament. But even in its wording the proposal provided the idea central to the essays on the formation of character (Donnachie, 2000, p. 115).

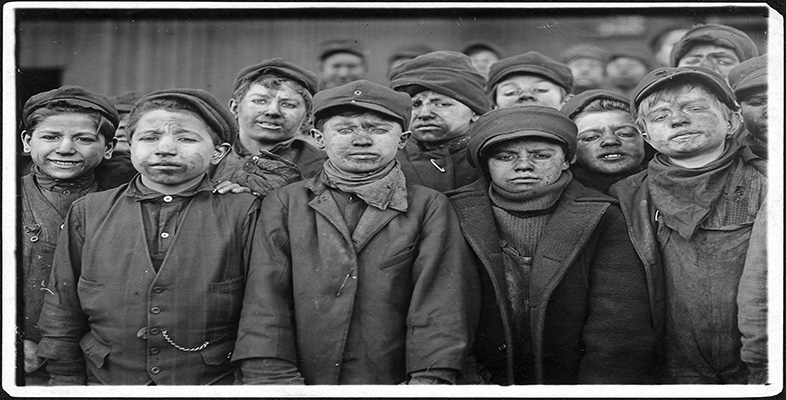

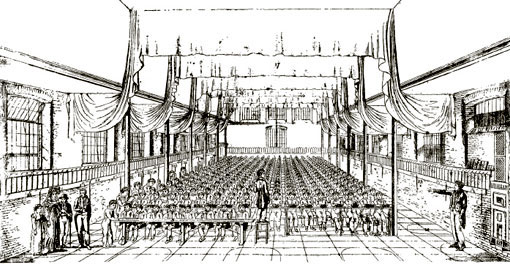

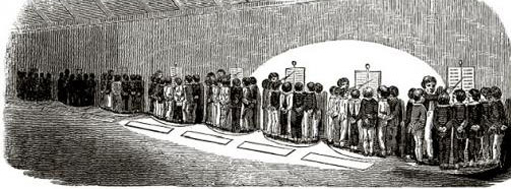

Another important development was Owen's involvement with Lancaster, whom he invited to visit Scotland in 1812. Lancaster had developed a method of schooling for working-class children based around rote learning and a system of badges and rewards (possibly the model for Owen's ‘silent monitor’, discussed in Section 6.4, used in the mills at New Lanark). By applying this system large numbers of pupils could be instructed simultaneously, with minimal expense on textbooks, something publishers must have regarded with alarm (see Figures 6a and 6b). Owen, flanked by professors from the university (Enlightenment Scotland having no fewer than four such seats of learning, compared with England's two) and by churchmen, chaired a dinner in Glasgow at which Lancaster explained his system, introducing one of his assistants to help demonstrate its key features. Owen's reply to Lancaster again emphasised the importance of working-class education as a means of social control and improved efficiency.

Owen's A Statement Regarding the New Lanark Establishment, published in 1812, was an important prelude to A New View of Society (see Figure 7). Partly a business prospectus and partly a summary of what he visualised for social provision at New Lanark, it describes his early management of the community. It also articulates his aspirations for the future and gives some indication of the way his thoughts were developing, many of which fed through to the essays. The extract in Exercise 6, below, will give you a flavour of what Owen was advocating for the community at this stage.

Exercise 6

Read the following extract from Owen's Statement. What, briefly, are his main proposals? What do they suggest about his proposals for social development and plans for communities?

It may be necessary to explain more particularly what I mean by those plans which I had in progress, for the further improvement of the community, and ultimate profit to the concern.

They were intended to increase the population, diminish its expense, add to its domestic comforts, and greatly improve its character. Towards effecting these purposes, a building has been erected, which may be termed the ‘New Institution’, situated in the centre of the establishment, with an enclosed area before it.

The objects intended to be accomplished by which are, first, To obtain for the children, from the age of two to five, a playground, in which they may be easily superintended, and their young minds properly directed, while the time of the parents will be much more usefully occupied, both for themselves and the establishment. This part of the plan arose from observing, that the tempers of children among the lower orders are generally spoiled, and vicious habits strongly formed, previous to the time when they are usually sent to school; and, to create the characters desired, these must be prevented, or as much as possible counteracted.

Secondly, To procure a large store-cellar, which was much wanted, and, by this arrangement, has been placed in the most advantageous situation for both the works and village; and it will be found to be of much use to the establishment.

Thirdly, A kitchen upon a large scale, in which food may be prepared of a better quality, and at a much lower rate, than individual families can now obtain it.

Fourthly, An eating room immediately adjoining the kitchen, one hundred and ten feet by forty within, in which those to whom it may be convenient may take all their regular meals.

Fifthly, The eating room, by an immediate removal of the tables to the ceiling, will afford space in which the younger part of the adults of the establishment may dance three nights in a week during winter, one hour each night; and which, under proper regulations, is expected to contribute essentially to their health.

Sixthly, Another room, the whole length of the building, being 140 feet long, 40 wide, and 20 high, which is to be the general education-room and church for the village, and those who attend the works.

Seventhly, This room was intended to be arranged, not only in the most convenient manner for the several branches of useful education enumerated, but also to serve for a lecture-room and church. The lectures were to be given in winter three nights in the week, alternately with dancing, and to be familiar discourses to instruct the population in their domestic economy, particularly in the methods they should adopt in training up their children, and forming their habits from their earliest infancy, in which, at present, they are deplorably ignorant.

And lastly, The plan also included the improvement of the road from the works and village to the old town of Lanark, which is now almost impassable for young children in winter, and in such a state as to prevent in a great measure the population of the latter from being available for the manufacturing purposes of the former, and from deriving any benefit from its institutions, which are calculated to educate the whole of the children in the neighbourhood, as well as the works are to give them employment afterwards.

Beneficial as these arrangements, connecting with the New Institution, must be to the individuals employed at the works, they will be at least equally advantageous, in a pecuniary view, to the proprietors of the establishment; for the whole expense of these combined operations will not exceed six thousand pounds, three thousand of which have been already expended; and, so far as my former experience enables me to judge of the consequences to arise from them, they cannot save less to the establishment than as many thousand pounds per annum, but probably much more.

(Owen, 1973, pp. 10–16)

Discussion

Owen says he wants to increase the population, reduce expense, enhance domestic arrangements and improve character. This will be done by developing the facilities of the ‘New Institution’, building a village store, establishing communal cooking and dining facilities, providing a dance hall, school and lecture rooms (doubling as a church), and improving communications with the neighbourhood. On a point of information, quite fascinating really, the ‘immediate removal of the tables to the ceiling’ was to be accomplished by means of hoists. This method of saving space was actually used elsewhere and it can be observed in the schoolroom scene (see Plate 2, linked below) where the ‘visual aids’ have been lifted off the floor.

Click to open Plate 2 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , G. Hunt, Dancing Class, The Institute, New Lanark, c.1820, coloured engraving, New Lanark Conservation Trust.

These proposals suggest that as early as 1812 Owen was already thinking in terms of social improvement driven by education and training. The communal arrangements for the supply of provisions and for cooking, dining and leisure activities are extremely interesting and might well have had wider application. There is also a hint of this in the penultimate paragraph, where Owen suggests these benefits will, in any case, be extended to the wider community beyond the confines of New Lanark.

We have no idea how many copies of the Statement he circulated, apart from those that ended up in the hands of potential partners. Possibly the work found its way into political circles, where anyone reading it would have been impressed by the idea that New Lanark under Owen's management

might be a model and example to the manufacturing community, which without some essential change in the formation of their characters, threatened, and now still more threatens, to revolutionise and ruin the empire.

(Owen, 1973, p. 4)

The idea that the character of the labouring class could be suitably moulded by these modest proposals, including whatever educational provision was required to make it more efficient (and thereby boost profits), was likely to have had considerable appeal in the increasingly volatile atmosphere of the time. As we have seen, political Radicalism in all its various forms was an anathema to the government, and the Luddites represented a direct physical threat to mill masters – or, worse, perhaps to the government itself. Riot and disorder threatened everywhere, but had not apparently reached the gates of New Lanark, another strong selling point. Equipped with copies of his statement Owen set out for London, hoping to put together a new partnership and secure control of the mills.