7 New Lanark as showpiece and text

Owen's partnership of 1814, consisting of Bentham and other enlightened individuals, mainly wealthy Quakers, paved the way for the rapid implementation of the innovations spelled out in the Statement of 1812 and subsequently in the essays. Two of the partners, William Allen (1770–1843), a chemist and businessman, and the wealthy and philanthropic John Walker (1767–1824), Owen's closest associate, were interested in education and had encouraged the establishment of schools adopting methods developed by Lancaster and others. Given their religious inclinations, they seemed strange allies, but Owen was able to deliver high returns on their investment, and for much of the time this may have counterbalanced worries about his views and propaganda campaigns.

The major developments took place in the mills, the community, the Institute and schools, with the last being the focus of attention for droves of visitors attracted to the place by Owen's publicity and the proximity to the Falls of Clyde. We can now see and hear discussed some of Owen's reforms for ourselves.

Exercise 19

Now view the rest of the video, below, and answer the following questions:

The mills: what were the major reforms on the factory floor and how was discipline enforced?

The community: what changes did Owen initiate in the community and what were the checks on people's conduct?

The Institute and schools: what were the main functions of these buildings and how were they organised? What curricula were followed in the various departments?

Click play to view the video (Part 3, 10 minutes)

Transcript: Introduction - Part 3

Discussion

On the factory floor the major reforms included (as we saw in the essays) phasing out the employment of children under the age of ten and introducing strict rules and regulations and a rigorous monitoring and reporting system. These actions greatly improved efficiency, productivity and profits. Owen also rebuilt on more modern lines one of the mills that had been destroyed by fire.

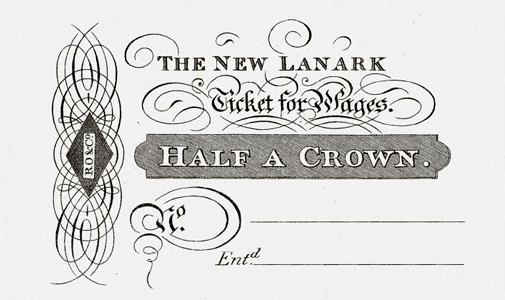

In the community a whole set of rules and regulations was issued governing everything from street cleaning to personal behaviour. Environmental improvements were undertaken, mainly to improve sanitation and water supply, but also including gardens, allotments and public walkways. Owen built more housing and housing stock generally was upgraded. A company store provided good-quality provisions at competitive prices, though workers were sometimes paid by cheque, the ‘ticket for wages’ (see Figure 9), exchangeable for purchases. The profits went towards subsidising the schools and the sick fund. (This looks distinctly devious, because in some instances no money changed hands and folk would be obliged to spend their wages at the store, enhancing Owen's profits twice over! But petty cash was in short supply at the time, so it was a neat solution to that problem.)

The Institute served as the main educational and social centre of the community. At first all the facilities were concentrated in the Institute, until the opening of a separate building for the school in about 1818 or 1819. As far as we know there was an infant department on the ground floor with a playground adjoining, and schoolrooms for older children on the upper floor. The Institute also provided facilities for evening instruction, lectures, concerts and dances, as well as for religious services.

The curricula, apart from the ‘three Rs’ designed to promote literacy and numeracy, embraced ancient and modern history, geography, natural history and what we might call civics or citizenship. All these subjects were promoted by the famous Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746–1827), whom Owen visited during his European tour in 1818. Numerous aids were deployed for the teaching of grammar, arithmetic and other subjects. There was considerable emphasis in the infant curriculum on play and the stimulation provided by the environment, with, apparently, a limited role for book learning. Again much of this probably came from Pestalozzi, who is thought to have been influenced by Rousseau's Emile (1762), another key text of the Enlightenment. At New Lanark children were also taught the ‘polite accomplishments’ of dancing (see Plate 2, below), singing and playing musical instruments, while boys, to the strains of the village band, engaged in military drill.

Click to open Plate 2 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , G. Hunt, Dancing Class, The Institute, New Lanark, c.1820, coloured engraving, New Lanark Conservation Trust.

Owen's son, Robert Dale Owen (1801–77), who as a US citizen was also to become a reformer of distinction, wrote a book entitled An Outline of the System of Education at New Lanark, first published in 1824, where he describes the schools and curricula. We can catch the flavour of this in a brief extract and by examining a picture of one of the schoolrooms and dancing children.

Exercise 20

Read the extract below and examine Plate 2, linked above. Comment on the scene. Does the extract give an accurate picture?

The ‘New Institution’, or School, which is open for the instruction of the children and young people connected with the establishment, to the number of 600, consists of two stories. The upper story, which is furnished with a double range of windows, one above the other, all round, is divided into two apartments.

The principal school-room, fitted up with desks and forms on the Lancasterian plan, having a free passage down the centre of the room, is about 90 ft long, 40 ft broad, and 20 ft high. It is surrounded, except at one end where a pulpit stands, with galleries, which are convenient when this room is used, as it frequently is, either as a lecture-room or place of worship.

The other apartment on the second floor has the walls hung round with representations of the most striking zoological and mineralogical specimens, including quadrupeds, birds, fishes, reptiles, insects, shells, minerals etc. At one end there is a gallery, adapted for the purpose of an orchestra, and at the other end are hung very large representations of the two hemispheres; each separate country, as well as the various seas, islands etc. being differently coloured, but without any names attached to them. This room is used as a lecture- and ball-room, and it is here that the dancing and singing lessons are daily given. It is likewise occasionally used as a reading-room for some of the classes.

The lower story is divided into three apartments, of nearly equal dimensions, 12 ft high, and supported by hollow iron pillars, serving at the same time as conductors in winter for heated air, which issues through the floor of the upper story, and by which means the whole building may, with care, be kept at any required temperature. It is in these three apartments that the younger classes are taught reading, natural history, and geography.

(R.D. Owen, 1972, pp. 28–30)

Discussion

We are in the schoolroom described by Dale Owen where three troupes of girls in uniform dresses dance (Scottish quadrilles?) to the music of a fiddle trio. On two walls are murals or visual aids (mounted on rollers) showing exotic beasts and a large map of Europe, described by Dale Owen. Parties of visitors, women predominating, look on, as do two persons clearly in supervisory capacities, at the lower right (possibly the benevolent Mr Owen and his son?). The extract certainly seems to describe the arrangements accurately and adds a great deal more detail about other facilities. (Dale Owen's book, incidentally, helped boost his father's reputation as an educational reformer.)

As pointed out in the video, the Institute and schools were the main items of interest for visitors. The nursery school was certainly pioneering and the subject of considerable comment in numerous accounts. John Griscon (1774–1852), an American scientist, educationist and reformer, visiting in 1819, described it as the ‘baby school’, pointing out its value to mothers working in the mills secure in the knowledge their infants were in safe keeping. So the promotion of nursery education could be seen as another simple device to promote efficiency. Another notable enlightened American, William Maclure (1763–1840), a founder of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and Owen's later associate in the New Harmony community, also praised this initiative. Seeing the many female visitors brought Maclure to the conclusion that women were more interested in education than men.

Of course, the use of New Lanark as a showpiece raises almost as many questions as its function as a test-bed for Owen's ‘New Society’. What were visitors shown and why? Just as significant, what were they not shown? Industrial espionage was a problem, so visitors were unlikely to be conducted round the mills, apart from the disruption this would have caused. There was much in the systems of policing, supervision and control, the regimentation in work and home, the communal activities and the indoctrination of children that was widely criticised. What did Owen mean when he talked of ‘happiness’? Was it not really ‘docility’? And while acknowledging some of Dale's achievements, Owen tried to deny New Lanark a history before his arrival as managing partner. These are some of the issues which might well have influenced the success or failure of the ideas set out in A New View of Society.