4.2 Social factors in the growth of the asylum: industrialisation, urbanisation and migration

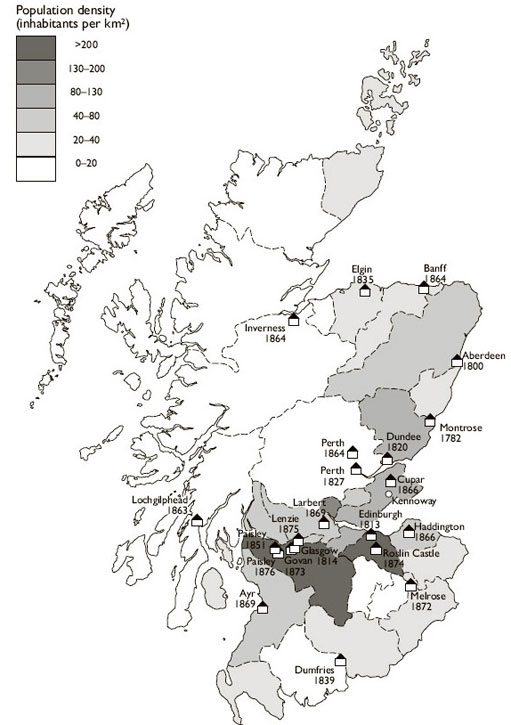

Many historians link the rise of the asylum with the huge social changes of the nineteenth century. Some link the rise to industrialisation and urbanisation, pointing to the fact that asylums grew up in industrial regions and large cities. Frank Rice, for example, argues that in Scotland the great majority of asylums grew up if not within urban centres, then at least servicing urbanised communities, in the central belt of Scotland (Figure 6). Only two of twenty-three Scottish private mad-houses identified as being in existence in 1855 ‘were situated outside the central belt’, and demographic research suggests that after 1811 there was never less than 81 per cent of the Scottish population concentrated within the urbanised central regions (Rice, 1985, p.44). Rice emphasises (but fails to offer specific statistics on) the chronological correlation between the size of Scottish towns and the number of institutions erected within them. Many cities appear to have embarked on new and enlarged asylum programmes out of a recognition of the inadequacy of existing, mainly urban-sited, provision for the insane in hospitals and poorhouses. Furthermore, Rice argues, these new asylums were built just as urban communities were attaining the peak of their industrial and demographic growth rates.

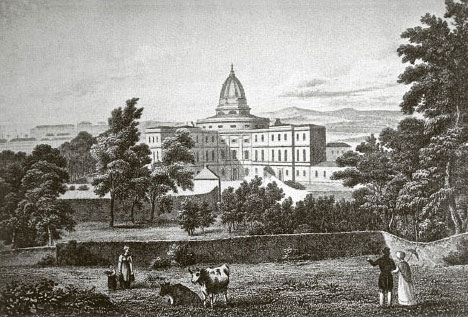

However, other historians have questioned the simplicity of the link between the new cities and the asylum. They point out that asylums were in many cases sited in rural areas that had little, or limited, industrial and urban growth. The first Victorian asylums were characteristically sited at some distance from towns and cities. The archetypal model of the nineteenth-century asylum, the Quaker York Retreat, opened in 1796, was a ‘retreat’ offering ‘asylum’ from the strains and stresses of everyday life (Figure 7). Early prints emphasised the idyllic situation of asylums, in expansive grounds with sheep and cattle grazing nearby (Figure 8). Many asylums' physician-superintendents emphasised the rural nature of their catchment areas, and the easy recruitment of staff from among the servants and farmworkers of the surrounding country. In England, as Scull argues, while rural communities enthusiastically built public asylums from the 1780s onwards, few of the counties in England's most industrial, urban Midlands and northern regions built asylums until obliged to do so by the 1845 Lunacy Act (Scull, 1979, p.29). Even in Scotland, it would be stretching the point to characterise Montrose (1781–2) and Dumfries (1839), the sites of two of the earliest asylums in Scotland, as highly urbanised and industrialised regions. Elgin, the site of Scotland's first district asylum for paupers only (1835), was even further distant from the central belt. The industrialisation–urbanisation theory also fails to explain why poor-houses with lunatic wards attached grew up in rural areas like Stranraer or Irvine. My own studies of the catchment area for Glasgow Asylum (later Glasgow Royal Asylum) during the first decades of the nineteenth century show how broadly the institution spread its net outside Glasgow and the more industrialised regions of Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire, with significant numbers of patients coming from the more rural regions of Argyllshire, Ayrshire and Fifeshire. Unfortunately, we still lack enough detailed surveys of the origins of Scottish asylums and their demographic profiles to attempt an overall model.

Another issue in question is whether or not the growth of asylums occurred at the same time as the growth of cities. Andrew Scull argues that the main growth of asylums took place before Britain was truly urbanised. While more than half of the populations of England and Wales lived in cities or towns by the middle of the nineteenth century, most of these communities were small. Only around one-third of the population lived in cities of 20,000 or more people. By this time, the asylum movement was well established, with all the major pieces of legislation in place and large numbers of asylums founded.

However, recent historical research has produced new evidence in two areas that challenges Scull's assertion that asylum-building preceded urbanisation and industrialisation. This work has shown that there was a significant phase of proto-industrialisation which preceded and laid the foundations for larger-scale industrial, urban and commercial growth. There was no radical divide between urban and rural areas in terms of industrial development, with many factories (especially textile works) and proto-industrialised crafts growing up within urban networks but closely linked to rural economies. Recent surveys of English urbanisation have emphasised the dramatic nature of the shift away from rural dwelling-places into townships and cities in the period c.1780–1850, and suggest that towns of 5,000 ought to be ranked as urbanised in contemporary terms (King and Timmins, 2001).

Scull and other historians have pointed to capitalism and the rise of an economy based on the payment of wages, rather than urbanisation or industrialisation, as important factors in the growth of institutional care for the insane. The next reading, from Scull's book The Most Solitary of Afflictions: Madness and Society in Britain, 1700–1900, reviews the debate over whether urbanisation or capitalism drove the increase in asylum populations.

Exercise 4

Read ‘The impact of industrialisation [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ’.

What aspects of capitalism does Scull believe contributed to the rise of the asylum?

Discussion

Scull argues that capitalism and the emergence of a commercial society in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, which occurred before large-scale industrialisation, destroyed the old ways of dealing with insanity within a domestic setting. A money-based, highly competitive economy broke the old social bonds between upper and lower classes that had helped poorer families to care for a mentally disordered person. In cities, where housing costs were high, families were unable to support an unproductive member, or to care for them, especially as their wages rose and fell dramatically during periods of boom and bust.

This is a very appealing argument. However, recent work by a number of historians suggests that we need to treat it with a certain degree of caution. This new research is built on a different approach: rather than trying to link a broad asylum movement with major social change, it focuses on particular institutions and the experience of individual patients, and forms part of the movement to study ‘history from below’. It uses hitherto neglected sources such as medical certificates, family members' descriptions of patients' behaviour prior to admission, and patient records from asylums. This provides a quite different perspective on the asylum, one that highlights issues of demand and need as well as supply. On the question of why patients were admitted to asylums, studies of accounts provided by the friends and families of the mentally disordered lend only qualified support to Scull's view that economic strain was the main trigger for seeking admission. Families and friends occasionally spoke of loss of income to the household through the expenses associated with nursing and managing a mentally disordered individual, through their own, or that individual's, inability to get employment. But there is little evidence yet from these sources that such rationales for committal figured any more prominently than they had done in previous times (Adair et al., 1998; Walton, 1981, 1985; Wright, 1998).

Similarly, detailed work on the geographical origins of asylum patients has also questioned the portrayal of the link between urban migration, social dislocation and the asylum. We might assume that the migration of families into towns in search of work would have loosened networks of support, and ultimately led to families placing members in asylums. The story is not that simple, however. My research on Glasgow Royal Asylum shows that although there were recent migrants to the city among the inmates, they were not a conspicuously large group. An extensive survey of the route to the asylum in the Devon region during the second half of the nineteenth century by Adair et al. (1997) has argued that the relationship of migration to asylum admission was actually the reverse – at least in some areas. They find that it was not the migrants who were more prone to end up in the region's asylums. On the contrary, it was ‘from the deeply rooted, physically less mobile and more socially entrenched families that the bulk of … patients came’, and thus from those sectors of society where kinship and household ties would be expected to be more resilient (Adair et al., 1997, p.393). Longer distance migration in Devon was actually associated with lower admission rates. The key factor here seems to be that insanity (like other forms of illness) prevented families from being mobile and moving into the cities.