2 What are the Ancient Olympics?

According to ancient scholars, the first ever Olympic Games were held in 776 BCE at the site of Olympia (in the district of Elis, on the Peloponnesian peninsula). This date was worked out by totting up the years from an early document that recorded Olympic victors. In fact, the roots of the Olympic festival probably stretch even further back in time to the Greek Bronze Age. Archaeological finds provide evidence of early manifestations of sporting events among the Mycenaeans and Minoans in the second millennium BCE, and there is a long literary tradition (particularly of Homeric texts) linking the development of Greek athletic festivals with funerary rituals that commemorated the deaths of local and mythological heroes (such as Pelops and Patroclus) whose funeral is related in Book 23 of Homer’s Iliad [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] .

From the 8th century BCE onwards, the Ancient Games were held every four years in Olympia. This quadrennial cycle was known as an Olympiad, and it became such a cultural landmark that long periods of time were often measured in ‘Olympiads’, i.e. four-year units, by Ancient Greeks. Recent research suggests that the intriguing Antikythera mechanism (a complex clockwork device from the 2nd century BCE that has baffled archaeologists for over a century) may have originally been used partly as an Olympiad calendar.

The Ancient Olympics were, of course, a sporting event, but there was much more to it than that. Athletics were intertwined with most aspects of life and society in Ancient Greece, including religion, art, identity, politics, law and literature. This relation can be seen, for example, in the large number of athletic scenes decorating the ubiquitous black and red figure Athenian vases; the abundance of references to athletic traditions found in classical mythology; the sports-related metaphors of Plato’s philosophical texts; and the combination of altars, temples, accommodation for high-status officials, monuments, treasuries, banqueting facilities and sporting grounds found at the site of Ancient Olympia. By the 6th century BCE, a Hellenic cultural identity had come into full existence, and the Games played an important role in underpinning this identity across the Greek world.

Interactive presentation

The following interactive presentation displays a series of literary quotes relative to the impact of the Olympics in Greek and Roman culture.

Participation in the Ancient Olympics was limited to free Greek male amateur sportsmen (Herodotus V.22.2). Non-Greeks, slaves, people accused of murder or blasphemy, and women (with some rare exceptions), were not allowed to compete. This might seem restrictive by modern Olympic standards. However, these regulations did not put off scores of people from flocking to Olympia to watch the Games, travelling from all over the Greek city-states and colonies as far afield as Africa and the Iberian Peninsula. At its height, the Ancient Olympic festival probably hosted over forty thousand people. According to tradition, it was believed that all these athletes and spectators were able to travel safely to Olympia under the protection offered by a sacred truce (the ekecheiria), proclaimed before the start of the Game by the spondophoroi (truce-bearing heralds who took the message of peace to various regions of Greece).

It is reputed that the Olympic sacred truce dates back to 884 BCE, when Iphitos (king of of Elis), the lawgiver Lycurgus of Sparta and Cleosthenes (archon of Pisa) followed the advice of the Delphic oracle and signed a pact to put an end to local disputes, which were interrupting worship at Olympia. The terms of this pact were engraved on a bronze disc, which was displayed for centuries in the Temple of Hera at Olympia, and became adopted as part of the Ancient Olympic tradition. Although a truce was ceremonially proclaimed before the start of each Olympic Game, in practice this did not always stop all conflicts. For example, in 424 BCE, the Spartans threatened to invade Olympia; in 365 BCE, the sacred grove was shockingly occupied by Arcadians and Pisatans while the Games were in full swing, and in 312 BCE Macedonians raided Olympia and plundered the treasuries. The situation was therefore not too dissimilar from some of our modern Games, which celebrate peace and embrace the theme of truce but, in reality, do not stop armed conflicts from being fought in various parts of the world.

Interactive presentation

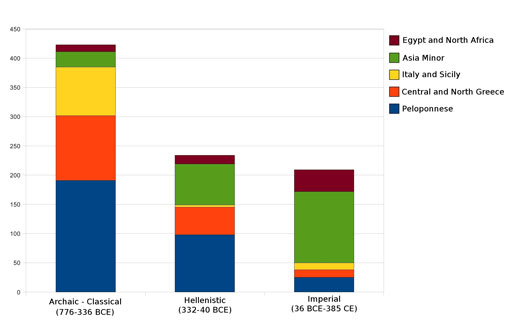

This interactive presentation will give you an illustration of the geographical diversity of the Ancient Olympic athletes. The earliest victors came primarily from mainland Greece and the Greek cities of Sicily and Southern Italy. However, areas such as Asia Minor and Egypt eventually came to dominate the victory lists in later periods. If you would like to explore more interrelations between these and other regions of the Ancient world, have a look at the HESTIA project.

In addition to their athletes, Greek communities sent sacred ambassadors (theoroi) as their official representatives to the Ancient Olympics. Theoroi were roughly similar to our modern diplomats. The coming together of theoroi united the Greek community, albeit temporarily. Their mission (i.e. their theoria), was a sort of pilgrimage. Theoria literally means ‘watching’ or ‘spectacle’ (from the same root as English ‘theatre’), a term which expresses their responsibility to watch the festival events on behalf of their community. As well as witnessing the festival, theoroi liaised with local leaders, represented their state in the official procession and sacrifice, and carried out a further sacrifice on behalf of their community. They also looked after the interests of their state’s athletes if any difficulties arose. Theoroi wore special wreaths (as the hero Theseus does in Euripides’s 5th century BCE play Hippolytus, lines 798-810; these showed that they were on sacred business and should not be harmed.

The Ancient Olympics lasted for over a millennium (from the 8th century BCE to the 4th century CE). This is, by most measures, a staggering amount of time for any festival to persist. During this period, the Games evolved from unofficial athletic rituals in the Dark Ages to a well-established quadrennial festival in the Classical period, developing later into a Romanised spectacle that would eventually degenerate into gladiatorial contests. The Olympics were constantly readapted to each period, with different durations, events and regulations. This course will focus principally on the Ancient Olympics at their zenith, around the 5th century BCE. However, as you make your way through the material in the following pages, try to bear in mind the duration of the Ancient Olympics and consider the ways in which the Games changed through time.

Interactive presentation

This interactive presentation shows how the Ancient Olympic Games evolved over time.