9 Day Five: Honouring the victors

The last day of the Ancient Olympics was dedicated to honouring the victors. You may remember from the introduction an image of goddess Nike holding a wild olive branch, decorating one of the medals that was awarded in the 1896 Olympics. Before the start of the Ancient Olympic festival, a boy whose parents were still alive cut various branches from a sacred olive tree (the kotinos kallistephanos), which grew in the Altis area of Olympia and, according to Pindar (Olympian 3.60 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ) , had supposedly been planted there by Hercules himself. These branches, which had to be cut with a gold sickle, were used to make the olive wreaths that were later awarded to Olympic victors.

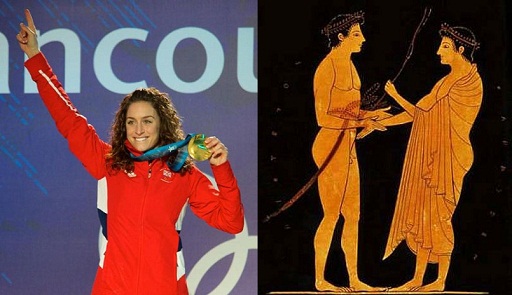

On the fifth day of the Olympics, the victorious athletes and ten Hellanodikai marched in procession towards the Temple of Zeus in the Altis. The olive wreaths were brought from the Temple of Hera, where they would previously have been on display on a gold and ivory altar. The victors, wearing ribbons around their arms and heads and carrying palm branches, passed before the Hellanodikai who ceremonially crowned them with the wreaths.

Animation 10 procession

As well as the ribbons, palm branches and the olive wreath, victorious athletes were awarded free dinners for the rest of their lives. Tempting as this might sound, compared to the financial rewards often granted by governments to modern Olympic victors, these prizes might seem something of a let down after such efforts and sacrifices. In fact, they were intentionally chosen to be ephemeral and with little or no material value in order to emphasise the fact that the real reward was the glory that came with the victory itself – the admiration of fellow citizens, the honour of having one's name entered into the register of Olympic victors and the satisfaction of Zeus (in whose honour the festival had been held).

So what’s the difference?: modern and Ancient Greek celebrations of victory in sport

What do you think are the main differences between modern and Ancient Greek ideas of victory in sport? How are these differences manifested in the honouring of the victors? Once you have come up with a few ideas, click on ‘reveal comment’ to read some of our suggestions.

Comment

The differences between ancient and modern Olympic victory have a lot to do with the contrast between the economics of religious sacrifice and those of the commercial market. In both contexts, however, there is a high value placed on human virtue as it is expressed in athletic performance. The enduring connection between striving, victory and virtue is at the heart of Olympic philosophy, ancient and modern.

The ancient Olympic victor was decorated with ribbons, a palm branch and a wreath of wild olive - symbols that dedicated him to the gods. Victory was less about receiving prizes than becoming a prize, a kind of offering to the gods. The modern Olympic victor, on the other hand, receives an enduring gold medal. The prize itself is not worth much money but the expectation is that it will attract lucrative commercial endorsements, professional sports contracts, even paid speaking engagements.

In recompense for the sacrifice of an Ancient Olympic victor, the gods were expected to benefit the community in concrete ways such as healing from disease or successful harvests. The victor therefore becomes a prized member of the community and is offered meals at public expense. At least one city’s confidence in the divine favour that a victory brought was so great that it even dismantled its protective walls for the athlete’s homecoming. The worth of the modern Olympic victory is based on marketing rather than religious beliefs, but at the same time it derives from similar ideas about the link between victory and virtue. We buy products that athletes endorse, watch them play sports, and listen to their speeches because we admire their virtues and hope to emulate them in our own lives. Olympic athletes inspire us even in our modern struggles.

The glory of ancient Olympic victory was characterised by its ephemerality. In contrast to the immortal gods, human excellence requires struggle and lasts only for a moment. But by resembling a god, if only for a moment, the athletic victor offers an inspiring example of our human potential. The transience of victory seems less emphasised today, but the reality is that Olympic glory rarely extends beyond the proverbial 15 minutes of fame. Modern Olympic medallists cash in quickly on their image, because it is soon forgotten. The general dream of Olympic victory, however, continues to inspire young and old alike.

Of course, many athletes used their Olympic victory as a platform on which to build highly profitable careers as high status, influential individuals. Their return home (eiselasis) was a momentous occasion. They were met by their families and fellow citizens and given a hero's welcome. A banquet and a symposion were normally organised by the athlete’s family in his honour. In addition, the wealthier families sometimes commissioned a life-size statue to commemorate the achievements of the athlete. The original statues are almost completely lost, but we can get a good idea of their visual impact from the copies set up in Roman gardens and baths and the description of Olympia by Pausanias. The different postures and equipment of the statues designate different contest disciplines, such as the hoplitodromos, pale and tethrippon racing. The powerful bodies in real-looking action poses were meant to convey the innate superiority of the aristocrats participating in the games. The practice of dedicating athletic statues began in the 6th century BCE and in many Greek sanctuaries soon produced dense accumulations of statues, as described by Pausanias in his writings.

If the athlete’s family were feeling particularly lavish and wanted to make sure that the news of the Olympic victory travelled far and wide, they had the option to commission a victory ode from a poet. These victory odes, which were created principally to extol the virtues of the athlete and his city, became an important element of the literary tradition of Ancient Greece. As Armand D’Angour explains (below), the victory odes of Pindar, in particular, were admired and regarded as masterpieces of literature.

Video: Armand D’Angour

Dr Armand D'Angour, author of the Pindaric Ode for Athens 2004 and the Homeric Ode for London 2012, tells us about Pindar and the tradition of ode composition as part of the honouring of victors in the Ancient Olympics.