8.2 Combat sports

After the last races had concluded, a brief intermission ensued to allow officials to dig up the skamma on the stadion surface, where the combat events would be held during the second half of the day. The combat sports of the fourth day were divided into two events: pyx (boxing) and the pankration (a form of all-in wrestling).

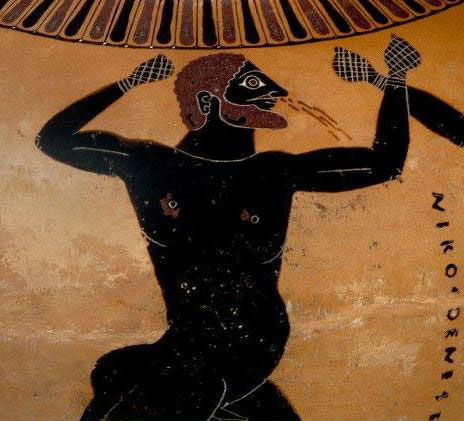

Pyx was not too dissimilar from our modern boxing. Competitors were only allowed to punch each other (it was forbidden to bite, kick or trip one's opponent). Despite these restrictions, it was still a fairly violent event (judging by scenes from decorated vases, which often show bruised and bloodied pyx fighters). The aim of a pyx match was to knock out the opponent (or force him to admit defeat, which was signalled by raising the index finger, as in pale ). Like modern boxing, pyx fighters did not compete bare-handed – they wrapped their wrists and knuckles (but not their fingers) with long straps called himantes. The himantes were made of tanned oxhide and measured approximately four metres. Their aim was to protect the fighter's hand (rather than the opponent's face). Unlike modern boxing, there were no rounds and a boxer could carry on hitting an opponent even after the latter had fallen to the ground.

Animation 9 boxing

Box 3 Highlight: the morality of violence in sport

Two men square up to each other in front of an excited crowd. The two fighters throw punches at each other and the crowd roars. Perhaps this is a confrontation on a city street on a Saturday night, and the police are arriving to make some arrests. Or perhaps this is a boxing match at the Olympics and the contestants are sporting heroes.

But is there a moral distinction between a street fight and a boxing match? Boxing raises a host of questions about the justification of violence and our attitudes to it. Ancient Greece had an ambivalent attitude towards violence. For instance, blood and death were not shown on stage in plays (with some exceptions), possibly because they were considered distasteful; but Ancient Greek mythology is rife with explicit examples of cruelty, revenge, war, rape and murder. Most people would agree that violence is sometimes justified – in self defence, for example. But is the quest for sporting glory a good reason for trying to land a punch on someone? And is it right that people should take pleasure in seeing two men try to hurt each other?

Perhaps the most familiar objection to boxing is the long-term harm caused to the boxers themselves. The British Medical Association has called for boxing to be banned, citing the damage done to boxers’ brains [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] . This raises broader questions about the role of law and its relation to morality. The BMA’s position can be seen as an example of paternalism – the view that one function of the law is to protect people from themselves. Opponents of a ban point out that boxers choose to fight, knowing the risks. Paternalism, they argue, is an unwarranted attack on freedom.

Pankration (which translates literally as 'all force') was perhaps the most brutal of all Ancient Olympic events. It was a combination of boxing and wrestling, without the use of the himantes. Like pyx, the aim was to knock out the opponent or force him to admit defeat). However, unlike pyx, most forms of physical aggression were allowed: kicking, punching, slapping, holding, tripping, and so on. The only restrictions were the rules against biting and gouging the opponent's eyes. Pankration was closely associated with the myth of Hercules, who, according to tradition, fought a lion with his bare hands (presumably resorting to some of the moves that came to be expected from a pankration match).

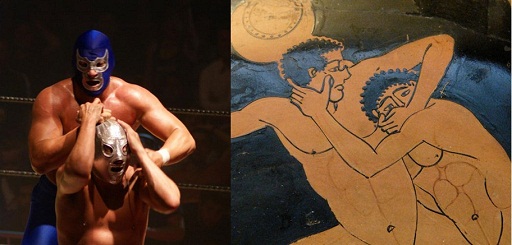

So what’s the difference?: modern Pro Wrestling and Ancient Greek pankration

What do you think are the main differences between modern Pro Wrestling and the Ancient Olympic pankration? Once you have come up with a few ideas, click on ‘reveal comment’ to read some of our suggestions.

Comment

Modern Pro Wrestling attracts large crowds. The atmosphere is riotous, with a mix of loud applause, cheering and booing. The public, who is titillated by the acrobatics and the more extreme forms of violence on the ring, incites the fighters with their shouts and gesticulations. Many of the wrestlers are already well known to the spectators – a few (like Hulk Hogan, Andre the Giant or Hacksaw Jim Duggan) have even achieved what some would consider star status.

So far, this does not seem too dissimilar from what we would expect to see in an Ancient Greek pankration match two and a half millennia ago. The Ancient Greek public standing around the stadion at Olympia cheered and reacted passionately to the sheer physicality of the event. Some pankratiasts had a cult following (like Theagenes of Thasos or Diagoras of Rhodes). In addition, the pankration, like a modern Pro Wrestling match, was not divided into rounds, had a referee (the Hellanodikes) observing the fight at close range and was fought until one of the opponents admitted defeat.

However, this is where the similarities end. Modern Pro Wrestling is not an Olympic event – it is a spectacle of the entertainment business, based mostly on theatre and choreography. Pankration, on the other hand, was firstly and foremost an athletic sport event. The wrestlers were not acting or performing rehearsed moves that had been agreed beforehand – they were competing for glory. Ancient Greek pankratiasts used no props (like the type of masks, extravagant sun shades, boots, chains, or even axes that we might expect from a WWF or Mexican Lucha Libre show); in fact they were completely naked! Unlike Modern Pro Wrestling matches, which are generally fought on an elevated wrestling ring with ropes, ring posts and a padded canvas mat surface, Ancient Greek pankration matches were fought in a simple skamma on the stadion.

All in all, pankratiasts were expected to act less like extravagant film stars and more like serious, focused athletes aspiring to achieve arete and kleos through their victory. Having said that, we do hear of cases where pankratiasts indulged in ostentation and antics. According to Polybius, the pankratiast Kleitomachos of Thebes once interrupted a fight mid-match to have a little chat with the public in order to criticise his opponent and try to gain the sympathy of the spectators!