7 Day Three: Sacrifices (Hecatomb) and feast

On the morning of day three, athletes, gymnastai, priests, and Hellanodikai gathered at the Prytaneion for the procession that would begin a day of sacrifice and feasting. Individuals would have been sacrificing animals on their own behalf at a range of altars, but this would be the official sacrifice, an impressive spectacle of great religious significance. Animal sacrifice was the central ritual act of Greek religion, so the sacrifice to Zeus would have been the focal point of the Olympic festival. Instead of a conventional architectural structure, Zeus was honoured by an unusual altar built from the ashes of the thighs of animals sacrificed there. According to Pausanias’s detailed description [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] (5.13.8-14.2), in his day the mound was 42 metres in circumference at its base and seven metres high, with flights of stone steps allowing access to the top. Tradition dictated that only the wood of white poplar should be used for Zeus’s sacrifices.

The worship of Zeus in the Peloponnesian peninsula long predated the Games. Greek gods were thought to watch and enjoy festivals much as humans did, so the procession had to be graceful and it was an honour to participate in it. The Hellanodikai led (two of them in the 5th century BCE, up to ten in the 4th century BCE), dressed in striking purple robes. They were followed by seers and priests, and behind them came 100 bulls, destined for sacrifice, led by watchful attendants. Then came the sacred ambassadors from across the Greek world, followed by the competing athletes with their gymnastai and closest friends. Watched by crowds of spectators, the procession (pompe) travelled along the Altis boundary and round to the Great Altar. Like all Greek altars, Zeus’s Great Altar was situated outside, where people could gather.

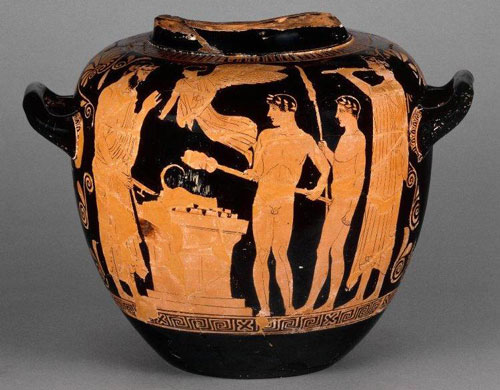

After ritual hand washing, prayer and the scattering of barley, the first bull would be stunned and its throat cut. Thigh-bones and fat, the god’s portion, would be burnt on top of the altar to please Zeus with their meaty aroma. With a hundred bulls to sacrifice, that aroma must have become quite strong. Sacrifices were usually more modest. This hecatomb – the sacrifice of a hundred bulls, involved a huge financial outlay as an especially generous offering to Zeus. As was standard practice at religious festivals, the killing was followed by a magnificent public feast, the meat being distributed amongst all present, with particularly good cuts going to the priests, other worthies and victorious athletes. In addition to barbecued meat, there would have been black-puddings made from the sacrificed animals’ blood, and local produce such as bread and olives, washed down by copious quantities of wine. Sacrifices were almost the only occasion when people ate meat, so the hearty meal and celebrations that followed sacrifices made religious festivals enjoyable and sociable as well as sacred.

Animation 7 sacrifices and banquet

In the Modern Olympics, the sacrificial and religious aspects of the ancient games have been substituted by an emphasis on national and cultural identity. The opening ceremony in particular sets the tone for the modern Games and presents the host nation with the opportunity to make a big statement. This takes the form of a series of spectacles that strongly reference its cultural identity and heritage. Television ensures that the images of the opening and closing ceremonies, as well as those of the athletic competitions themselves, travel instantly across the globe and help to shape the international reaction to the hosting country’s organisation of the games. The Modern Games have thus developed their own complex series of ceremonies and rituals. These have, however, been divorced from any religious or sacrificial connotations; rather they are designed to emphasise national identity under an umbrella of international cooperation.