5 Day One: The opening ceremony (athletics and religion)

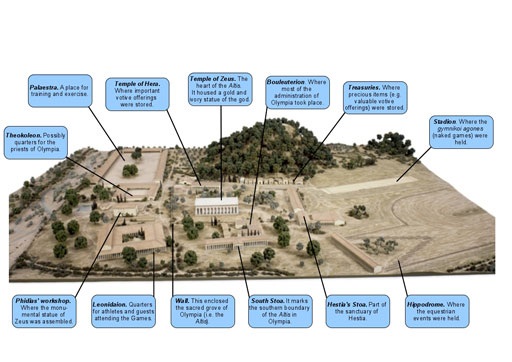

The Ancient Olympics were, in essence, a religious festival. The Games were held in honour of the god Zeus and almost all aspects of the athletic events and the rituals that surrounded them were connected with the realm of the sacred to some degree. This Olympic association between athletics and religion was made clear from the outset – the first day of the Games was dedicated principally to religious ceremonies. This level of devoutness, which might strike us as unusual compared to the secularity of modern Olympism, could be explained partly by the fact that Olympia had never been a city in the traditional sense – it was half sanctuary, half sports grounds compound. The site of Olympia was broadly divided into two sections by a large wall – the area where the athletic spectacles took place, and the Altis, or the sacred grove, where temples, halls, altars and the treasuries were located.

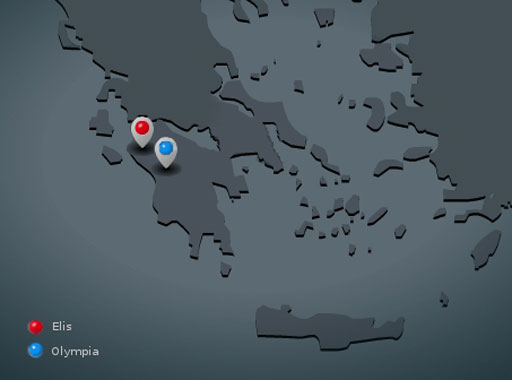

When the Games were not being held, only a handful of officials and priests lived in Olympia. Most of the people who controlled and supervised the Games lived in the nearby town of Elis. In fact, the religious ceremony that opened the Olympic festival started in Elis, rather than Olympia itself. A large group of several hundred athletes, who would have gathered in Elis several months earlier in order to complete their training under the supervision of the ten Hellanodikai, began marching towards Olympia the morning before the start of the Games. They were accompanied by their families and entourage, the Hellanodikai, the fifty members of the Olympic council and the horses and chariots of the equestrian events. This mighty procession took one day and one night to cover the 36 kilometres that separate Elis from Olympia.

Just before arriving, they stopped at the Pierian spring, a sacred site where the Hellanodikai were sprinkled with the blood of a sacrificed boar and washed in the spring’s waters. Purified by this ritual, they proceeded towards Olympia. A massive crowd waited for them there – thousands of spectators, traders, magicians, peddlers, scholars trying to spread their philosophies, lawyers, painters and sculptors displaying their works. According to Epicteus (I.6.23-29 [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] ), writing in the 1st century CE, the noise and activity were overwhelming. When they arrived at Olympia, the Hellanodikai and athletes made their way to the Bouleuterion (council house). There, athletes would be classified into age groups (in order to ensure a fair competition) and give an oath in front of the statue of Zeus that they would commit no evil act during the Games. They would then proceed to one of the many altars in the sacred grove, where they would make an offering to Zeus, Hermes, Apollo or Hercules and pray for victory.

Box 2 Highlight: Hercules and Pelops – founding heroes

The foundation of the Olympic Games is usually attributed to one or both of the heroes Hercules and Pelops. The Hercules tradition goes back at least as far as the early 5th century BCE, when Pindar’s victory ode Olympian 10 (476 BCE) tells how Hercules laid out the sanctuary and ‘established the four years’ festival with the first Olympic games and its victories’ (ll.55-9), after successfully cleaning the stables of the local King Augeias. Lysias’s Olympic Oration 33 (written around 400 BCE) asserts that Hercules envisaged the games as conducive to ‘mutual friendship amongst the Greeks’.

The Pelops tradition also first appears in an ode by Pindar of 476 BCE (Olympian 1.93-6), which tells the story of his chariot-race against the Elean king Oinomaos for his daughter Hippodameia’s hand, and concludes with mention of the ongoing fame of the contests on the racecourse of Pelops. Hippodameia is supposed to have established the girls’ games of Hera’s Olympian festival in thanksgiving for her marriage (Pausanias 5.16.4).

Both heroes’ victories were celebrated in sculpture decorating the Temple of Zeus. Pelops’s chariot-race was prominently featured in the east pediment, over the entrance, while metopes depicting the twelve labours of Hercules were placed within the east and west porches. The Pelops story may have provided inspiration especially for charioteers, but the muscular Hercules is clearly a role model for all aspiring athletes. Sacrifices were regularly made to Pelops at his shrine within an ancient enclosed grove near Temple of Zeus, and to Hercules at an altar supposedly founded by the king Iphitos who re-instituted the Games in 776 BCE (Pausanias 5.4.6 and 5.14.9).