2 1823: the birth of prison education

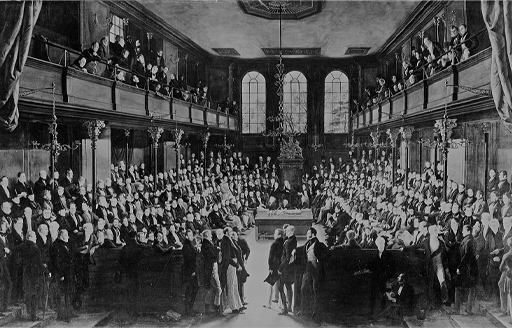

In 1823, MPs at Westminster did something momentous. They passed new legislation (the Gaols Act) aimed at improving conditions in prisons which included the following clause:

Provision shall be made in all Prisons for the Instruction of Prisoners of both Sexes in Reading and Writing…

While it is true that the Gaols Act applied only to England and Wales, and only to around one-third of all local prisons in those two nations, it was still highly significant. It reflected steps already being taken in prisons across the four nations of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England to provide prisoners with instruction in reading and sometimes writing.

Why was legislation passed for England and Wales and not for Scotland and Ireland? The particular penal and educational circumstances of each nation provide an answer. In 1823, there was no national system of elementary education in England and Wales. Several attempts by MPs to introduce one had failed. The failure of one education bill, on which many hopes were pinned, coincided with the insertion of the ‘reading and writing clause’ into the 1823 Gaols Act. In other words, penal legislation was used to bring about educational reform more broadly (Crone, 2022, ch.1).

Irish penal reform legislation predated that for England and Wales by a couple of years, and this timing could explain why a similar clause had not appeared in the Irish Prisons Acts. Penal reform was delayed in Scotland, but there was also perhaps less urgency for prison education there because Scotland already had a national system of elementary education of sorts: parish schools. This was lacking in the other nations. Educational and penal reformers in the decade leading up to 1823 proclaimed that lower crime rates in Scotland, compared with England, Wales and Ireland, were the consequence of its parish school system.

After 1823, education continued to spread across penal institutions in all four nations. You’ll look at how, and to what extent, in Session 2. First, you’ll take a closer look at where this idea of educating criminals came from.