7 Christian Evangelicalism

One proposed solution to the social crisis was the promotion of Christianity, or the evangelisation of the masses. In 1800, about 90% of the UK’s population were Christians. Despite this, social elites believed that many of the poorer people had stopped attending church and knew little about God. Reacquainting them with the Bible, they argued, would secure social harmony and reduce crime.

Proponents of this belief were leaders of an Evangelical revival which began around 1740. This movement led to the formation of an Evangelical party within the Church of England, the revitalisation of older dissenting congregations (such as the Society of Friends, or Quakers, and the Independents), and the formation of new denominations, notably Methodism. All placed great emphasis on personal salvation and individual access to the Bible. The ability to read was therefore an essential tool for Christianisation. Instruction in writing helped to reinforce the skill of reading and to aid the memorisation of key messages from the Bible.

Evangelicals of all stripes took a particular interest in prisons and prisoners. John Wesley (1703–91), the founder of Methodism, preached at least 67 times in prisons, raised money for clothing and blankets and encouraged followers to visit prisons too. His campaigns led the authorities at Bristol’s Newgate Prison to separate male and female prisoners, end drunkenness, and provide Bibles for prisoners to read. Wesley provided inspiration for penal reformer John Howard who was himself an Independent.

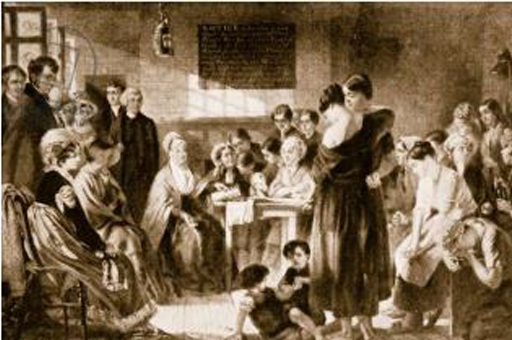

After 1800, Quakers took a leading role in the penal reform movement. Most famous was Elizabeth Fry (1780–1845). After visiting Newgate Gaol in 1813, Fry successfully campaigned for the improvement of conditions on the female side of the prison. She also established a school for children imprisoned with their mothers which was later expanded to include adult prisoners.

As a result of Fry’s efforts, prison visiting became fashionable and associations of lady visitors were established throughout the UK. Quakers, some of whom were related to Fry, banded together to establish the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline in 1816. In this undertaking, they were joined by several leading Church of England Evangelicals. Focused on redemption, or the saving of souls from damnation, Anglican Evangelicals believed that the country’s most troubled and troublesome people – alcoholics, slaves, prostitutes and prisoners – needed Christianity.