9 The expansion of education

Both Utilitarians and Evangelicals favoured the spread of education. They were united in the idea that literacy could have ‘a profound impact on the mental and moral character of the individual and by extension [wider] society’ (Vincent, 1989, p. 6).

Members of both movements were involved in the expansion of education in England, Wales and Ireland from the late 1700s. As Scotland already had a parish school system, the task was considered less urgent. In Ireland, England and Wales, Christian bodies moved to supplement the teaching of the poor provided by private schools (i.e. schools run by working men or women who were themselves barely literate). Sunday schools (which were not only for children) appeared in the 1780s and spread throughout England, Wales and into Scotland.

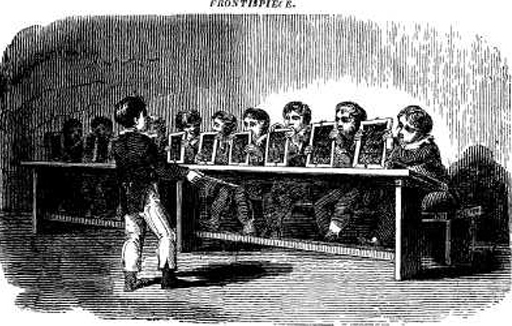

In England and Wales, two rival school societies were established, the British and Foreign Schools Society (1808), which was run by Christians who did not belong to the Church of England (non-conformists), and the Church of England-run National Schools Society (1811). Both promoted a system of teaching called ‘monitorial’, in which pupil-monitors assisted trained teachers to drill their peers to memorise the letters of the alphabet and build up to words. Concerns about adult illiteracy led to the establishment of an ‘adult school’ by non-conformists in Nottingham in 1798. Methodists began an Adult School Movement in 1812. By 1818, there were more than 200 adult schools in England and Wales.

Reports published by the school societies and MPs at Westminster increasingly proclaimed that crimes were most often committed by those with the least education. Low levels of crime among Quakers, who were often highly educated, and Scots, who had access to a national system of education, were cited as evidence. Thomas Pole, one of the founders of the adult school movement, wrote in 1816:

By a comparison of the criminal calendars of England and Scotland, it is found that criminal offences are ELEVEN times more frequent in England, in equal portions of the population, than they are in Scotland! … What constitutes the difference? In Scotland the poor are educated – in England they are not.

This view, combined with the expansion of education in British and Irish society, and the role of Quakers and Utilitarians in the penal reform movement, led to experiments with education in prisons. In 1814, the Coventry Branch of the National Schools Society helped to establish a school for juvenile offenders in Warwick County Gaol (Crone, 2022, ch.1). The chaplain at Millbank Penitentiary was tasked with providing instruction in reading and writing when the prison opened in 1816.

Reports of inspections carried out by the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline in Britain and the Association for the Improvement of Prisons and Prison Discipline in Ireland revealed the development of many more schemes, some of which were quite advanced. At prisons in Sligo, Naas and Carrickfergus, for example, schoolmasters were employed to teach reading, writing and arithmetic to prisoners.

Activity 3 What have been the reasons for supporting learning in prison?

- Summarise the reasons why reformers in the early 1800s promoted the education of prisoners.

- Note any other reasons you can think of which support the case for prison education.

Discussion

Reformers in the early 1800s promoted the education of prisoners for the following reasons:

- Crime rates were lower among educated people.

- Reading enabled the personal study of the Bible which led to moral improvement.

- Literacy offered a means of self-improvement, and therefore a solution to poverty.

- Literacy was seen to have a profound impact on the mental and moral character of an individual and therefore on wider society.

Other reasons for providing education in prisons might include:

- Studying can give prisoners self-confidence and a sense of personal achievement.

- Through education prisoners can gain skills which will be useful on release.

- Having evidence of learning might aid a prisoner’s case for parole.

- Educated prisoners are less likely to return to prison.

There are some important similarities between these two lists. In the early 1800s and today there is a belief in the transformative potential of education – that the ability to read and write and the acquisition of new knowledge can change a person’s life for the better. You will explore this theme further in the sessions that follow. How did the authorities try to harness the transformative power of education? How successful were they?

At the same time, it is important to remember that education can be used for other purposes too, some of which have little to do with improving lives. Education can be used as a tool for pacification, or to occupy otherwise idle prisoners. In certain forms it might also serve as a tool for discipline. The magistrates in charge of Reading Gaol in the 1840s supported the programme of rote learning (the memorisation and recitation of passages of text) carried out there because they saw its value as a punishment. They believed it was more irksome than some forms of hard labour.