1 Tracking the spread of prison education

From the 1820s, as a result of the penal reform movement, the central government began to collect information on prisons in Britain and Ireland. Two new prison inspectors in Ireland began to visit and to deliver official reports on prisons. Their reports showed that arrangements to teach reading and writing were being made in many prisons.

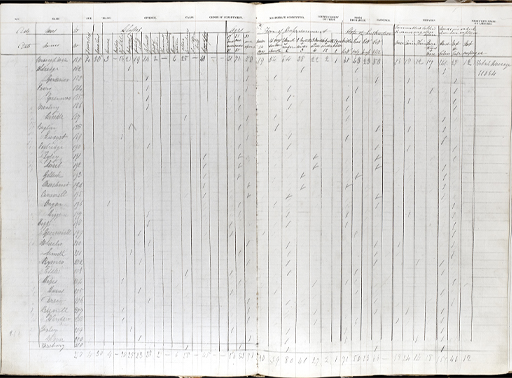

In England and Wales, those who managed the gaols and houses of correction which came under the terms of the 1823 Gaols Act were required to submit annual reports to the Home Secretary. Governors had to provide information about the number of prisoners and to say whether prisoners had been supplied with books and given instruction. Chaplains were asked to remark on the ‘condition’ of prisoners. Often, they described how many prisoners could read and write and what they were doing for those who could not.

Reports mentioned the appointment of teachers, the purchase of books and writing equipment and the use of prisoners to help teach reading and writing. They suggest that education was spreading through the local prison sector, albeit slowly. Historians who use these documents need to recognise that when reporting to the Home Secretary governors might have wished to highlight some issues and minimise others.

Concern that so many prisons in England, Wales and Scotland remained unreformed – either because they were not covered by the 1823 Gaols Act, or because the prison authorities refused to comply with it – led to calls for the establishment of a British prison inspectorate. In 1835, five inspectors were appointed. Four men covered England and Wales and one covered the whole of Scotland (as well as part of north-east England for a time).

They were primarily information gatherers. They could remind prison governors of the legal requirement to instruct prisoners, and they could recommend changes to education programmes, but they could not force governors to act. The inspectors were also inconsistent in their approach. Only some took a keen interest in education. Where they found that arrangements for instruction had not been made, they did not always insist that prisoners should be educated.

Nevertheless, education spread. Between 1823 and 1850, it appears that many local prison officials were keen to introduce education, either because they believed in its transformative potential, or because they saw it as a useful tool for discipline and maintaining order, or both. The prison inspectors’ reports also suggest that the spread of prison education was driven by the closure of small, inefficient prisons which could never have provided prisoners with instruction. As small prisons closed, and those which continued to operate grew bigger, education in prisons became more likely and cost-effective. So, from around 1850, while the number of prisons with education programmes stabilised, the proportion of prisons with programmes continued to rise, until it reached approximately 100 per cent in the 1800s (Crone, 2022, ch.1).