2 Inclusion and exclusion

Even though arrangements to instruct prisoners in reading and writing might have existed within a prison, it does not mean that every prisoner in that prison had access to education. In convict prisons in Britain and Ireland, where populations were larger, and convicts remained for much longer periods of time, efforts were made to educate men and women, adults and children alike, even though the physical separation of these groups created a need for bespoke arrangements. Because the teaching of reading and writing was often bound up with moral instruction, and the Bible was used as the principal text, there was a strong belief that all could benefit from attending school, whatever the level of their knowledge. In practice, those prisoners working in the prisons as cooks, bakers, cleaners, nurses or in artisanal trades, were often unable to attend classes, and infirmary patients also tended to miss out.

Populations were even more fragmented in local prisons. Legislation required that male prisoners were kept separate from female prisoners, that prisoners awaiting trial (or on remand) were kept separate from those who had been convicted, and that petty offenders (i.e. misdemeanants) were kept separate from serious offenders (i.e. felons).

Physical separation could lead to exclusion from education. For example, in the 1820s and 1830s female prisoners frequently missed out because there were often relatively few of them and because they required special arrangements. Male schoolmasters and chaplains could only teach them if a female officer was in the room. Female prisoners were often dependent on instruction offered by the matron (if she had time and was able) or charitable lady visitors. Male juveniles were sometimes given instruction in order to separate them from adult male prisoners, who were left uninstructed. Over time, barriers to education based on gender and age eroded (Crone, 2022, ch.1).

At some local prisons the authorities experimented with compulsion. Daily attendance at lessons was made compulsory at Chester County Gaol in 1836, and by 1838 no one was exempt from attending classes taught by the schoolmaster (in the presence of the matron for the female prisoners) at Leicester County Gaol (Inspectors, Northern & Eastern, 2nd Report, 1837, p. 17; Inspectors, Southern & Western, 4th Report, 1839, p. 222).

However, participation in scholarly instruction in most local prisons was voluntary, and in 1843 new rules and regulations drawn up by the Home Office and circulated to local prisons in England and Wales stated that prisoners should not be compelled to ‘receive instruction’ (Regulations for Prisons, 1843, rule 129). Instead, it was suggested, and in many prisons enacted, that access to education should be given as a reward for good conduct. Prisoners aged under 17 years, however, were usually forced to attend school while in prison.

Some local prison officials questioned whether prisoners confined for short periods could benefit from instruction and restricted access to education to those with sentences of three months or more. This worked against female prisoners, who tended to be imprisoned for much shorter periods than men. Often prisoners who were already able to read, or read and write, were excluded from the prison school, though they continued to receive some religious instruction. A small number of officials began to suggest that some prisoners were unable to learn how to read and write. In 1835 the chaplain at Swaffham House of Correction argued that the prisoner aged under 25 might be taught to read in six months, but for those above that age it was much more difficult and many refused to learn (Inspectors, Northern & Eastern, 1st Report, 1836, p. 48).

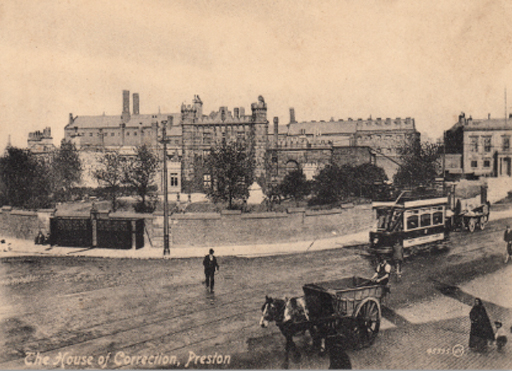

Activity 1 Arrangements for instruction at Preston House of Correction

Read the following extract from the annual report of the Rev. John Clay, prison chaplain at the Preston House of Correction, for the year 1825. As you read it, take notes which address the following questions:

- What arrangements were made to teach prisoners to read at this prison?

- Were they effective?

- What might have been the benefits of such arrangements?

- Can you think of any drawbacks?

Annual report of Rev. John Clay, 1825

A system of mutual instruction is still practised among the prisoners of all classes. They are supplied with the necessary books; and it is generally found that those who can read are not only willing, but in many cases anxious, to instruct their more ignorant fellow prisoners … In the two principal wards of the prison, viz., the misdemeanants’ and convicted felons’, rooms are appropriated to a school, and it is not an unusual thing to find on a Sunday morning twenty-eight or thirty prisoners in the former, and fifteen or twenty in the latter – all of them assembled by their own free choice, and all of them occupied in giving or receiving instruction…

Discussion

- At Preston House of Correction prisoners were supplied with ‘the necessary books’ (i.e. elementary books) and encouraged to teach each other to read.

- The chaplain seems positive about the arrangements. He says the prisoners are ‘anxious’ to participate. However, we do not know how many learned to read as a consequence.

- There were multiple benefits. Not only was the arrangement voluntary but prisoners were actively engaged in their instruction. Learning from a peer with whom you can identify can be effective and it can foster self-confidence. It was still the common practice outside prisons for children to learn from literate adults or older children. There were benefits for the prison too. Instruction could take place in existing spaces in the prison and during times when prisoners were not working (in this case, Sunday morning). You might have noticed the reference to ‘misdemeanants’ (petty offenders) and ‘felons’ (serious offenders) – these two classes of prisoners were supposed to be kept separate. These arrangements did not interfere with prison classification systems.

- As for drawbacks, these arrangements depended on the existence of prisoners who knew how to read well enough to teach others. This might have been a problem in prisons with smaller populations, or among female prisoners who were often a small group and who had to be kept apart from male prisoners.