3 Ways of educating

Education within the prison took a variety of forms. In some prisons, like Preston House of Correction, prisoners were given books – primers, spelling books, and grammars – and writing implements – pens and paper or pencils and slates – and told to instruct each other. While some chaplains found prisoners were uninterested, other chaplains were impressed with how they got on. The governor at Louth House of Correction declared in 1837, ‘[the prisoners] instruct themselves as well as they can, and it is quite wonderful to see in this way the improvement they make’ (Inspectors, Northern & Eastern, 3rd Report, 1837–38, p. 52).

More often, some kind of teacher was appointed to instruct the prisoners. Sometimes a literate prisoner who had behaved well filled the role. Other times, the authorities benefited from the visits of a charitable lady or gentleman who took it upon themselves to teach the prisoners to read and write. One of the most famous prison visitors was Sarah Martin who, between 1818 and 1843, taught the prisoners at Great Yarmouth Borough Gaol to read and write (Rogers, 2009).

Family members of prison officers were also asked to teach. At Ely Gaol in 1849, the governor’s daughter, aged 11, taught the female prisoners. Prison officers – warders, matrons, and even chaplains – sometimes stepped in to provide instruction. At some prisons, paid schoolmasters, or, less often, paid schoolmistresses, were employed to teach the prisoners (Crone, 2022, ch.1).

Officials, then, drew on a range of available resources in order to teach prisoners to read and write. However, as you shall see, those arrangements which appeared to offer the least disruption to the penal environment – such as prisoners teaching each other – or required minimal financial outlay – the use of prisoner-schoolmasters, charitable visitors, or family members – soon proved to be the most problematic for the authorities.

Activity 2 Silence and separation

In the Introduction to this session, you watched a short video on the rise of silence and separation, two competing forms of prison discipline that appeared in the mid-1830s. Take another look at any notes you made. Considering the various ways in which prisoners were taught to read and write, what impact do you think the imposition of silence or separation might have had on prison education?

Discussion

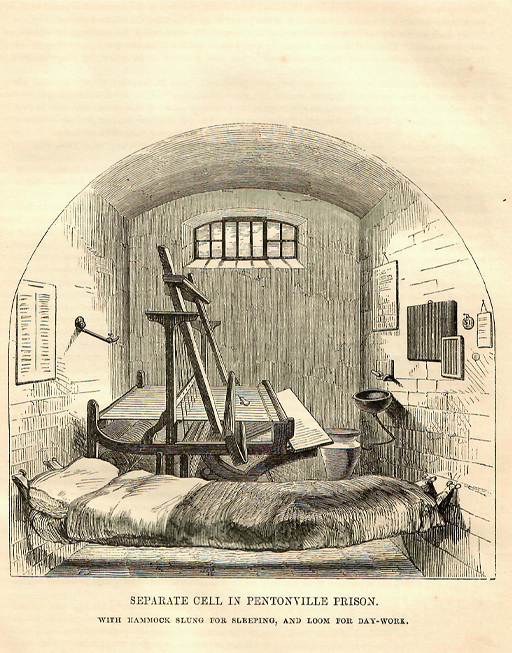

Under the silent system, although prisoners remained in association, any form of communication between them – verbal, written or physical – was strictly prohibited. Under the separate system, prisoners were locked in solitary cells as much as possible, and were also forbidden to communicate when brought into association for exercise or chapel services.

These rules on contact between prisoners meant that forms of mutual instruction or peer learning were abolished. Prisoners were also no longer able to be appointed as teachers. In some prisons, in consequence of the imposition of silence or separation, prisoners were left without instruction for some time until new arrangements could be made.

At the same time, education in prisons became more important under both the silent and separate systems. The ability to read provided mental relief for prisoners, and could protect at least some from depression and mental illness. Separation in theory relied on prisoners being able to read the Bible, and to understand its messages of Christian salvation, especially when the visits of the chaplain were necessarily short and few and far between.