6 Time for instruction

Education – when delivered by appointed teachers to classes of prisoners – needed designated time in the prison timetable. Initially, prison officials attempted to schedule school when prisoners were not at hard labour or employed in other types of work.

Sundays presented one option, if instruction in reading and writing could be done during time set aside for religious instruction, and if sufficient prison staff could be secured to supervise prisoners. Evenings were another possibility but only in prisons with a gas supply for artificial light; before 1850, few local prisons in Britain were illuminated after dark (McConville, 1981, p. 360). In larger prisons, including convict prisons, the sheer number of prisoners enrolled in the prison school often meant that there wasn’t enough time on Sundays or in the evenings to teach everyone.

Therefore, in most prisons, officials were left with no alternative but to schedule classes during the day and to withdraw prisoners from labour. Some officials complained that prisoners used school to escape part of their punishment. Others protested that labour interfered with education. Where prisoners were paid for their labour, or where non-completion of hard labour tasks led to punishment, prisoners refused to leave their work to attend school.

Activity 5 Timetabling

This course is likely to take you at least 24 hours to complete. It is recommended that you study it over eight weeks. This could allow you time to think over questions and compose responses.

This course is not just about the history of prison education. It is also about how to read historical sources. Understanding the context in which a source is produced, and whether it is written by a witness or a later historian, helps us to interpret it. Being sensitive to different perspectives and being empathic to other people’s cultures or the experiences of minority groups can often be crucial to your ability to solve problems and interpret meaning.

Learning all this can take time and energy. Now that you are a few hours into the course you should have an idea as to how long it took you to complete the first session. This activity provides ideas about planning your study time for the whole course.

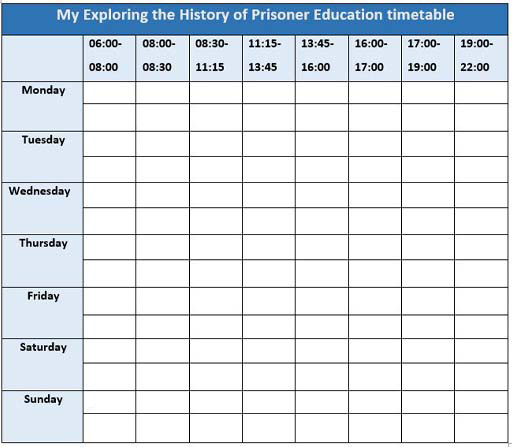

Complete the grid below with your ideas for study time. You might find it easier to make your own grid.

- Start with your non-study activities. Put in mealtimes and sleep. You’ll need to go online to complete the quizzes which occur at the end of each session. If your online access is restricted put that in and plan around it.

- Studying after a full day can be tiring. Even if you feel motivated now, you are advised to build in some time away from studying.

- Once you have drafted your grid, look at the discussion below. While scheduling is a matter for each individual, seeing the ideas of others can be helpful.

Below is an example grid.

You can find an editable Word version of the grid when you access the following link: Example timetable [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)]

Discussion

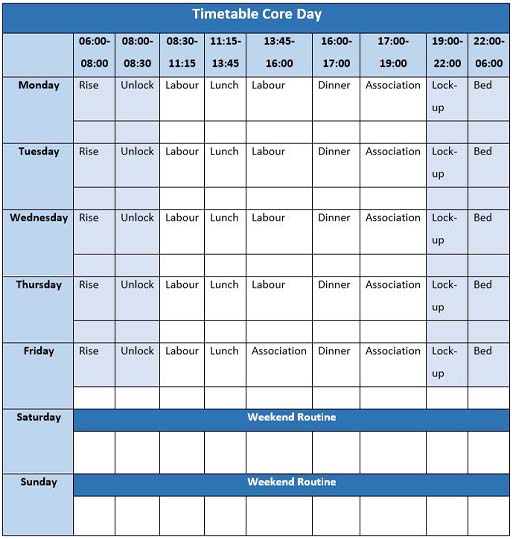

Here are some examples produced with the help of former prisoner learners and mentors.

Access the following link to get a larger version of the table.

The above timetable is the basic prison core day. Most prisons follow this sort of regime, with some variation on the times. If you are a prisoner you will have to negotiate with the prison staff, and Education Provider’s staff for access to the Open University’s Virtual Campus. If you are a prisoner who is in a double-cell you will also need to negotiate time with your cellmate so that you can study. This is not easy when you share a small room from 1900-0800 each day.

Access the following link to get a larger version of the table.

This timetable was the schedule of a prisoner. He added ‘My early morning study was the time that I used to read material without taking any notes, and then I would type up notes during the afternoons when we had dedicated Distance Learner access to the IT equipment!’ He had to be focused and dedicated.

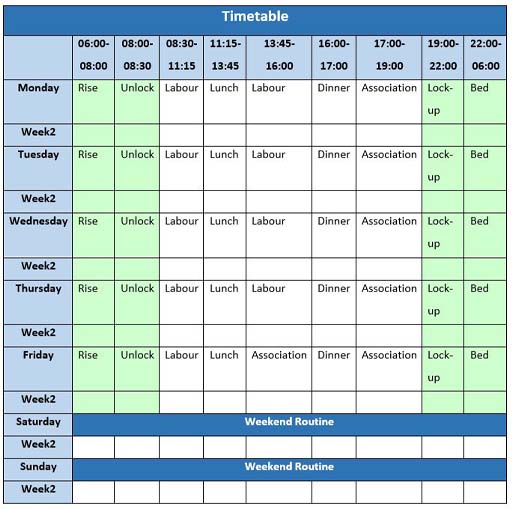

Access the following link to get a larger version of the table.

The ex-prisoner who produced this timetable added:

There is time for most learners in custody to study the basics of the course work within the coloured green time zones. You will see that I have used this single grid to create a two-week timetable – which I think is probably the best route to go down in prison and secure environments. That way the study workload can be spread over a longer period and allowing a more concentrated effort in the time given to study. I have found that prison employers are much more accepting of a timetable over a longer period rather than taking the same time off each week.

You can of course develop your own timetable that works for you, and these examples are not intended to be prescriptive. The aim is to plan your time effectively, and this is a useful and transferable skill which can apply to other activities as well.