1 Searching for the causes of crime

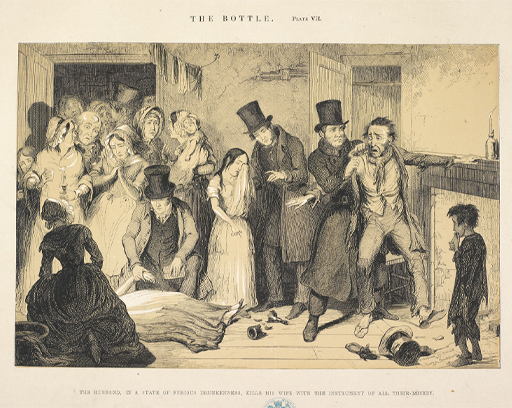

By the 1830s, Britain was once again in the grip of a social crisis. Industrialisation (the rise of manufacturing) and rapid urbanisation (the movement of people from the countryside to towns) had led to a deterioration in living conditions and the expansion of poverty. Unhealthy and overcrowded neighbourhoods – or slums – had become a common feature of most large towns and cities. At the same time, crime rates continued to rise, and some groups of people began to express their unhappiness through rioting.

The government was eager for solutions, and prison chaplains, with their easy access to those who had been convicted of crime, were keen to contribute. In order to illuminate the causes of crime, prison chaplains began to interview prisoners and to collect information about their lives. Foremost among them was the Rev. John Clay, chaplain at the Preston House of Correction from 1823 to 1858 (Forsythe, 1987). His reports were filled with tables which described prisoners’ degree of literacy and religious knowledge, and which demonstrated a close relationship between the commission of crime and drunkenness.

The evidence from Clay and other chaplains was used to demonstrate that crime was a consequence of increasing immorality which was in turn largely caused by a lack of education – both scholarly and religious. In support of this view Clay used extracts from the testimonies of prisoners – collected via interviews, or in letters addressed to him or others – in his annual reports.

The evidence that Clay collected needs to be treated with some caution. When giving an account of their lives, prisoners, like other people, might have left out information or restructured it, or they might have lied. In a conversation with a chaplain, prisoners might have had reasons to manipulate their stories. They might have wished to try to gain early release or other privileges, to deflect their guilt, or to avoid a taboo subject.

However, such accounts can also provide useful information and a different viewpoint from official records. Even if they draw on stock narratives about the causes of crime or life in prison, prisoners’ testimonies can shed light on the lives of individuals outside the prison, and tell us how they coped inside the prison. As with all sources, prisoners’ testimonies reflect the biases of the authors, and of those who collected and arranged them for publication.

Activity 1 Testimonies of prisoners

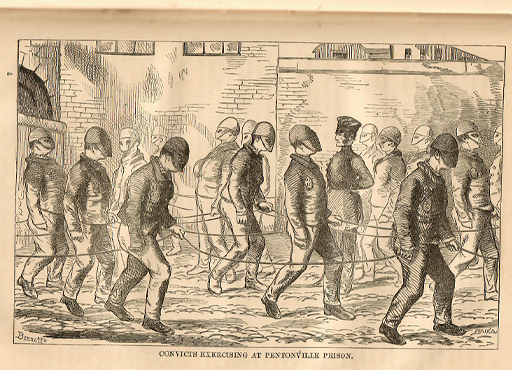

The Rev. John Clay was a firm supporter of the separate system of prison discipline. He argued that the moral condition of individuals would improve if they were kept apart from other prisoners and conversed solely with the chaplain. Clay was keen to prove that the separate system could be a success and that the Scriptures aided reform. Clay encouraged prisoners confined in separate cells to review their lives as a part of a process of repentance and reform. Between 1843 and 1846, Clay took personal testimonies from 1,234 males and 199 females (Clay, 1846, p. 21).

The testimony of J.M., aged 17 and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment for a felony (a serious offence), was included in Clay’s annual report for 1849. Read the following extract from J.M.’s testimony and then try to answer the following questions:

- What does J.M. consider to be the cause of his criminal behaviour?

- Comment on the language this prisoner uses. Does anything strike you as a little odd or out of place?

- How authentic, or trustworthy, do you consider J.M.’s testimony to be?

J.M.’s testimony

My mother did her best to send me to Sunday School, and I believe I should have taken her advice, but for seeing my father’s bad example. There is one lesson it has learnt me, that is never to be a drunkard, as bad as I am. If my father had been as my mother, instead of being in prison I should have been in an honourable situation.

Discussion

- In his testimony, J.M. does not mention his own guilt, but instead blames his father for the bad example he set (presumably by drinking too much). J.M. suggests that if he had listened to his mother, and continued to go to Sunday School – that is, a school held after church services on Sunday in which reading, writing, and Christian values were taught – then he might have got a good job rather than ending up in prison.

- J.M.’s overall language is quite formal. He may well have called his parents ‘mother’ and ‘father’, especially when talking to the prison chaplain. The words ‘drunkard’ and ‘honourable situation’ appear more contrived. Perhaps J.M. was echoing terms he had picked up from Clay. The phrase ‘it has learnt me’ sounds odd and unnatural. It looks like an attempt by J.M. to employ the language of another rather than to explain things in his own words.

- You could read this material as evidence of J.M. asserting his right to provide an account of the past. Perhaps you think J.M.’s emotional plea was a hypocritical attempt to win round Clay and gain concessions, such as access to books, a better diet, or time off his sentence. He would have known that these were the right things to say to Clay who was a religious man. There is also a possibility that Clay tailored the material he recorded. In his reports, Clay was very keen to emphasise the negative consequences of alcohol as well as the effects of religious ignorance. In 1848 he wrote ‘Religious ignorance is the chief ingredient in the character of the criminal. This combines with the passion for liquor’ (Bennett, 1981, p. 80). An account like J.M.’s was perfect for proving his point.